I’m still in catch-up mode (another way of saying “behind the curve”), so here are some updates to keep the blog going, poor neglected thing that it is.

With reference to my previous post, every scrap of information that’s since come out about the Asiana crash in San Francisco bolsters my initial impression: pure pilot error, no mitigating circumstances. The press is always deferential toward airline pilots, pussyfooting around even the most egregious cases of pilot buffoonery, and at least for the first week or so they tried hard to give the Asiana bozos the same treatment, going off on irrelevant tangents about automation and the difficulties of flying landing approaches at busy airports. Now, though, it’s become obvious, even to the press, that these pilots simply were not up to the job.

And yet Asiana certified them, put them in one of their most sophisticated aircraft and turned them loose in international airspace, letting passengers think they could safely put their lives in Asiana’s hands. Seriously, would you ever fly that carrier again? Oh, okay, I didn’t really mean that (yes I did) and I’m sorry for the outburst (no I’m not).

I hope I didn’t mislead anyone earlier into thinking I know much about cockpit automation. I don’t. I never flew any airplanes that had it. The closest I came was flying the F-15, which has a two-switch pilot relief mode, and that’s it. One switch lets you hold a steady altitude; the other lets you hold an attitude. You have to be level at the altitude you want before you can engage altitude hold; similarly, your attitude (bank and/or pitch) has to be stable before you can engage the attitude hold. You can engage one or the other, or both at once (if, for example, you want to stay straight and level at a set altitude). It’s handy because it allows you to take your hand off the stick when you have other things to do, but in no way is it an “autopilot” … you can’t fly instrument approaches with it or change speeds, altitudes, or headings. And you can’t trust the thing, which is probably true of even the most sophisticated airline automation systems.

Basically, we hand-flew the F-15 at all times. Some exceptionally lazy pilots might engage attitude hold on a long, gradual descent: once you set the correct pitch and desired descent rate you can engage attitude hold and have one less thing to worry about for a while. I’ve done that once or twice, up at altitude … but never close to the ground.

Airline cockpits are heavily automated. You can fly modern airliners with the autopilot, using it to hold or change altitude and headings; many systems incorporate an auto-throttle to control speed. You can even fly instrument approaches with autopilot, all the way to touchdown. Pilots can become reliant on these systems. If they become too reliant, their hand-flying skills atrophy. It’s an issue and a number of professional airline pilots are worried about it.

I can relate, even though I have no experience with automation. What I had, or I should say “the thing we F-15 pilots had that older pilots who flew older fighters didn’t have and therefore thought F-15 pilots were not as good as they were because we had it,” was the head-up display, the HUD. We fought heads up, looking out of the cockpit, weapons parameters and aiming information projected onto the HUD, overlaid on top of the actual target on our nose. Most of what we needed to know was displayed on the HUD, eliminating the need to constantly look down into the cockpit. In the landing pattern, basic flight and important instrument information appeared on the HUD, once again allowing us to fly while looking outside the cockpit. We didn’t have to go heads down to fly an ILS, unlike pilots of older aircraft. When you’re flying right down to precision approach minimums, being heads up is a big deal … you’ll be looking right at the runway when you break out of the crud at one hundred feet, a quarter mile from the landing threshold.

The old heads called us “HUD babies” and worried that our ability to fly instrument approaches off the needles and round dials inside the cockpit had atrophied. Any chance they got, they’d rag us about “HUD addiction,” telling us to turn the HUD off in good weather and practice instrument landings without it. Having flown a much older jet before I came to the F-15, the T-37 trainer with its 1950s-era cockpit and no HUD, I understood where the old heads were coming from and would practice no-HUD approaches from time to time. Besides, HUDs can quit working, and indeed they let me down once or twice.

But when the weather was shitty and I had to be on course and glide path in order to land, I’d fly the HUD every time. And who wouldn’t? So if an airline pilot can fly a better ILS with full autopilot, using it to control course, glide path, and speed, I understand. If an airline pilot has to hand-fly most of the approach because the ILS is out, but wants to use auto-throttle to take some of the load off, I understand. But he or she had better know how to use cockpit automation correctly, and he or she had better monitor those systems constantly by cross-checking speed, course, and sink rate … not to mention the visual picture out the front window. Asiana Flight 214’s crew failed on all counts.

Well. In other flying-related news, I finally put my F-15 PowerPoint slides together, along with my notes and talking points. Now all I need to do is practice.

I’m giving a presentation on the F-15 to Pima Air & Space Museum staff and volunteers on September 21st. I’ll be talking about the F-15C Eagle, the “light gray” as opposed to the “dark gray” F-15E Strike Eagle (a totally different airplane, despite its outward similarity to the Eagle). I’m going to address the Eagle’s development, weaponry and radar, combat record, some of my own experiences flying the jet, past and current basing, and plans for its future.

PowerPoint. When I retired a few years ago I thought I’d seen the last of it, but here I am up to my ass in slides again. Surprising how much of it comes back. Would you like to see one of my slides?

I picked that one because it shows the F-15’s instrument panel and the HUD I was just telling you about. You can see how buried in the cockpit you’d be without the HUD, and you can compare the information projected onto the HUD with the same information down on the cockpit instruments and gauges. Pretty nifty. But here’s something even niftier:

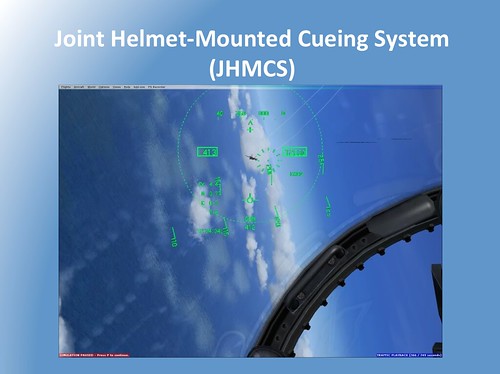

Yeah. No more HUD. Now the symbology’s projected onto the inside of your helmet visor and you see it no matter which direction you look. Damn, I wish this stuff had been around when I was still flying the jet!