Obviously we don’t yet know what happened to cause Asiana Flight 214 to crash at San Francisco International last Saturday. Anything I say will be speculative, but based on what I’ve seen, heard, and read to date, it sure looks like the pilots, through their own actions or inactions, got low and slow on final approach to Runway 28 Left and hit the sea wall with their tail about a thousand feet short of the normal touchdown point.

Some news reports mention that the Instrument Landing System for 28L was down, but not much should be made of that. When you’re lined up with a runway, ILS provides precise course and glide path information. It’s primarily used for landing during bad weather, poor visibility, or darkness. Granted, most airline pilots today use it in good weather as well, coupling it to their autopilots to keep the airplane on course and glide path, but in visual conditions you can always hand-fly the airplane, and that’s what these pilots were doing: hand-flying in clear weather with excellent visibility.

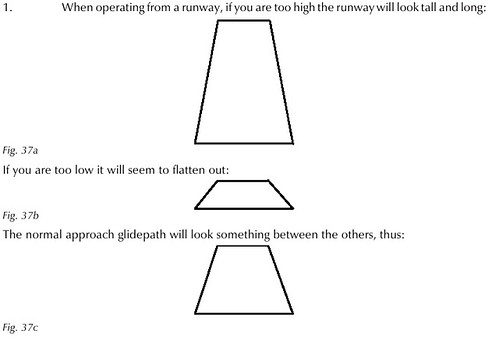

One of the first things a student pilot learns is to safely land an airplane: to recognize what the runway looks like on a 3-degree glide path, how to manipulate throttles and controls to stay on runway centerline, glide path, and speed. This is basic stuff. How basic?

Imagine you’re in the car with your spouse. You’re coming home from a shopping trip and … let’s say your husband’s at the wheel … as he turns into the driveway he doesn’t line up with the garage. He’s going to hit the wall if he doesn’t straighten out. You keep thinking he will, but he doesn’t, and just as you’re about to say something he smacks into the wall. That’s how basic.

Flying a hands-on visual approach in good weather is as simple as steering your car into the garage (okay, maybe a little more difficult because of the added vertical dimension, but still). You don’t get your pilot license if you can’t do it. That’s how basic.

Which is why I’m ignoring the issue of the accident pilot’s experience in the Boeing 777. Which is also why I’m ignoring the PAPI lights. We’re talking basics. The accident pilot had thousands of hours at the controls of similar passenger aircraft. A plane is a plane; you fly them all the same way. A proper glide path looks the same whether you have PAPI lights or not.

Here’s how a normal approach to runway 28L at SFO should look:

The pilot is flying a 3-degree glide path, aiming for a touchdown point about 1,000 feet down the runway (about where those two big white squares are). If you’re high and flying a too-steep glidepath, the runway will appear to be long and tall. If you’re low the runway will appear flat, and if you get really low it’ll almost look as if you’re flying up to it. Like this:

Once again, this is basic stuff. If you start to go below the desired glide path, you pull back and add a little throttle to get back up to it. If you’ve gotten slow as well, you’ll need more power. If you’re really low and slow, plenty of cues start clamoring for your attention: the flat appearance of the runway, the need to pull the nose higher and higher, airspeed warning signals, stick shakers and other stall warnings, and—one would hope—the other pilot screaming in your ear and wresting the controls away from you.

Go back to that driveway situation for a second. You’d have said something to your husband well before before he drove into the wall, right? I hope so!

We know what the speeds were. We know what the glide path was. We know where the tail section first contacted the seawall. The NTSB has the black boxes and cockpit voice recordings. The pilots, the witnesses who had the best seats in the house, are alive. What we don’t yet know is what was going on in their minds. Apparently the more experienced pilot (who was not at the controls) didn’t try to correct the mistakes the lesser experienced pilot was making until it was too late. Was he simply not paying attention, or was something else going on? I understand the NTSB is interviewing the two pilots today, so this information should come out soon.

If, as I suspect, the non-flying pilot was aware of the worsening situation but reluctant or unwilling to correct the pilot at the controls until things had gotten too far out of hand, this will become one of those classic flight crew screw-up accidents, a perfect example of a breakdown in crew resource management, and will be taught to new airline crews everywhere. But I don’t know that yet, so it’s a subject for a future post.

As a side note, on Saturday when I heard the first reports of Asiana Flt 214 “cartwheeling” after the crash, I posted this to Facebook:

That was before I saw the crash video. My apologies to ignorant journalists everywhere.