Latest update (10/3/25): added a link to an excellent hands-on tour of a B-58, including extensive information on the crew escape pods.

If my fighter pilot friends are wondering about me after my earlier post on the F-101B Voodoo air defense interceptor, they’ll surely think I’ve lost my grip now, fetishizing over, of all things, a bomber.

You have to admit, the B-58 Hustler was a mean machine, IMO the coolest bomber ever, a product of the speed-is-everything 1950s. I’m sorry to say I never saw one in the air, despite growing up in the 1960s when they were flying. But perhaps that’s understandable: only 116 B-58s were built, and they were based at bomb wings in Texas, Arkansas, and Indiana, far from any of the places I lived then. I would love to have seen and heard one of these beautiful machines.

Well, at least there’s one I can look at whenever I want: it’s on display at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, where I volunteer as a tour guide. I can never walk past our B-58 without stopping and staring. Even standing still, paint fading in the sun, its engine intakes covered, it looks like it’s busting through the Mach.

The Soviet Union detonated its first atomic bomb in 1949, four years after ours. By 1953—one year after we tested our first H-bomb—they had those too. Even though the USSR was right behind us in nuclear bomb development through the late 1940s and early 1950s, the US Air Force thought it was still possible to get a leg up on the Soviet Union with a high-altitude supersonic nuclear bomber—at the time the USSR simply didn’t have the capability to shoot one down. This was the genesis of early research and the USAF’s 1951 Supersonic Aircraft Bomber project, which in 1953 resulted in a contract for Convair to begin work on what became the B-58.

The prototype B-58 flew in November 1956, followed by a three-year flight test program involving up to 30 test aircraft. Designing and testing a bomber built to fly twice the speed of sound at altitudes in excess of 50,000 feet was still scary stuff in the mid to late 1950s, and that perhaps explains the lengthy flight test process—we were exploring new territory with this exotic and complex airplane.

The USAF declared the B-58 operational in March 1960. In addition to the test aircraft, Convair built over 80 production B-58As, with the last one rolling off the line in October 1962 (as it happens, my museum’s B-58A is the last one delivered to the USAF). Starting around 1960 Convair began converting the test aircraft to operational status, for a total B-58A fleet of 116 aircraft.

The Hustler had a short life span: the fleet flew for just ten years. By the end of January 1970, they had all been retired.

By the time B-58s began flying for the USAF’s Strategic Air Command, the USSR had of course caught up with us again and now had surface-to-air missiles capable of shooting down high-altitude supersonic bombers (a capability they convincingly demonstrated in May 1960 when they shot down an American U-2 spy plane flying up around 80,000 feet). Because of that threat the B-58 was never employed in the role for which it was designed; instead SAC employed it as a low-altitude penetration bomber. The B-58 flew well at low altitude, but it was only barely supersonic in the denser air and its fuel consumption went through the roof, limiting its range.

SAC had initially resisted the B-58, feeling it was an unnecessary weapons system that had been forced down its throat, an expensive and dangerous one at that. A B-58 cost approximately three times as much to acquire as a B-52, and over its life cycle proved to cost three times as much to maintain. It was a handful to fly with high cockpit workloads for all three crew members (pilot, bombardier/navigator, and defensive systems operator). Loss of an engine at high speed, especially an outboard, could put the airplane into a high yaw condition that was particularly treacherous. Over its life, 26 Hustlers were lost in accidents, nearly 25% of the total fleet.

In spite of the Hustler’s shortcomings, once SAC started flying the airplane it adopted a more proprietary attitude and began developing tactics for its use. By 1965, when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara declared the B-58 non-viable and directed its retirement, SAC had become a staunch defender of the Hustler. SAC and Convair had plans on the books (never to reach fruition) to acquire 185 improved B-58Bs, and was even thinking about a Mach 3-capable B-58C.

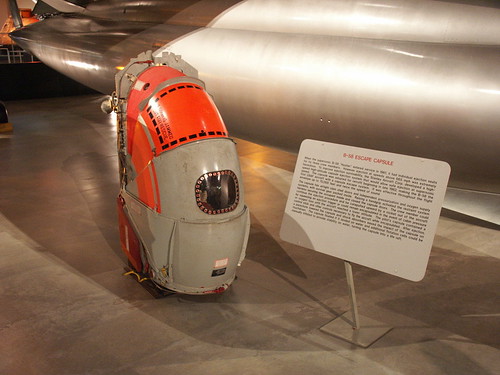

One of the more interesting components of the B-58 was the escape capsule, designed to protect its occupant in the event of a high-altitude supersonic ejection (the pilot’s capsule actually incorporated flight controls so that he could continue to fly the aircraft once he’d closed the clamshell around himself).

The Hustler carried fuel in internal wing and fuselage tanks. The jettisonable belly pod carried additional fuel, in addition to a single free-fall nuclear bomb. With later versions of the pod, the fuel-carrying portion could be jettisoned, leaving just the bomb. At some point hardpoints were added to allow external carriage of four additional free-fall nuclear bombs (the B-58 carried only nukes—it had no conventional bomb capability whatever). Self defense was provided by a 20mm rotary cannon in the tail, controlled by a tail mounted radar but activated by the DSO in the aft cockpit.

The B-58 could be fitted with a photoreconnaissance pod; there were plans for electronic countermeasures and cruise missile-launching pods as well. One B-58 was modified to carry and flight test the J93 engine designed to power the XB-70 Valkyrie bomber, and during flight test of the XB-70 a B-58 was used as a chase plane. Another B-58 was used to test a prototype air-launched ballistic missile.

Despite the Soviet Union’s demonstrated capability to shoot down high-altitude supersonic bombers, at some level the USAF has never abandoned the dream. I think immediately of the previously-mentioned XB-70, developed in the 1960s even after the high-altitude supersonic bomber concept was clearly no longer viable; a less obvious follow-on (mainly because no one is yet openly talking about it in this context) is the USAF’s unmanned X-37B space plane prototype, which recently returned from a 15-month orbital mission (during which no one but the USAF was able to track it). Heh. Shoot that down, Putin!

Links: