The day after the FBI raid on Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort, this popped up in my Twitter feed:

Rachel Vindman, of course, is the wife of retired Army Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman, whose military career was destroyed by a vengeful commander-in-chief after Vindman testified to Congress about Trump’s attempt to coerce Ukraine’s president into digging up dirt on a political rival, Joe Biden.

Rachel’s tweet may not make a lot of sense to those outside the DoD, but I knew instantly what she meant by it: that Trump had continued to come after her husband even after forcing him out of the Army, most likely trying to make trouble for him with a trumped-up(!) investigation into how he handled classified material while still in uniform. And more than that: Rachel’s showing that Trump and his cronies understood the rules of handling classified material quite well — well enough to try to use those rules against a perceived enemy.

In my Air Force career, I managed to get in trouble twice over classified material. For the first screwup, I received a written reprimand. The second screwup, thank goodness, turned out not to be mine — had it been, I might have wound up in Leavenworth. Unlike Alexander Vindman, I hadn’t made any enemies. Had someone higher up the chain been actively trying to end my career, he probably would have succeeded.

Oh, you want the piggy dirties? Happy to oblige, so long as you understand why I still have to be vague about certain details.

In the spring of 1982, two WWII aces visited Elmendorf AFB, Alaska, where we were making a new home for the F-15 Eagle fighter. We’d just begun converting the squadron from the F-4 Phantom II to the F-15, and there were only two Eagle pilots on base to show the visitors around, me and my boss Crumer. We didn’t even have any F-15s to show our guests — the new aircraft wouldn’t start arriving for another few weeks. But we had a brand-new F-15 simulator, built for the Saudis but for some reason canceled and given to us instead.

I was detailed to give the two WWII aces a tour of the sim facility, and to talk them through flying it. One of the men was Ken Taylor, one of the few American pilots to get airborne and engage attacking Japanese aircraft over Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. The other was a Zero pilot named Saburo Sakai, a Japanese ace many times over.

Both men took turns flying the sim, but then, with several minutes left to kill before the next scheduled event on their tour, I showed them the simulator instructor’s console, including a screen showing a menu of enemy aircraft, anti-aircraft artillery, and surface-to-air missiles the sim instructor could sic against the pilot in the sim, threats that would appear and behave in realistic ways on the cockpit scopes and screens.

Fifteen minutes after returning to the squadron, the wing commander’s hotline on my desk lit up. “Skid,” he said, “did you show those guys something you shouldn’t have?” Before he even finished asking the question, four Alaskan Air Command intel officers in class As, men I’d never seen before, surrounded me at my desk and motioned for me to hang up the phone. They then frog-marched me to a SCIF at AAC headquarters, where they grilled me about who I was working for and what else I might have shown our uncleared visitors. I didn’t even know what I’d shown them in the first place, let alone anything else.

What had happened, I finally learned, was that one of the visitors’ escorts had seen a Secret NOFORN label on the menu of simulator threats I called up, and ratted me out. During the 10-day investigation that followed, I was restricted to non-classified work and forbidden to leave the base. Fortunately for me, they interviewed F-15 pilots and simulator instructors at units in Europe, the US, and Japan, discovering that most of us had no idea the information on that screen was classified. Only one of the sim instructors they talked to, as I recall, had ever noticed the Secret NOFORN label on the threat menu.

I was cleared, but with a strong slap on the wrist as a warning to others: a written reprimand to stay in my records for a year. By the time I was up for promotion to major, two years later, the bad stuff was no longer in my file and I made it, so no long-term consequences. Still, it scared me and left an impression.

Good thing, too, because my new-found caution around classified material saved my ass during the second incident, which otherwise would have been career-ending (or worse). In 1988, when I was a joint staff officer at US Special Operations Command at MacDill AFB in Florida, the then-deputy secretary of defense for readiness asked our commander, an Army four-star, for a detailed readiness report on the nation’s special operations forces: Navy, Army, and Air Force. As the J3 readiness officer, I was put in charge of the team writing the report. It was a massive effort, and the result was a 400-page door-stopper of a document. There was a main section, which I mostly wrote and which we initially classified secret, and a smaller top secret annex put together by the snake eaters back in USSOCOM’s SCIF.

In January 1989, on the eve of delivering copies to the deputy secdef, the USSOCOM commander, the DoD, and the JCS, an intel puke (those guys again!) said the entire report ought to be reclassified as top secret, with the annex upgraded to a need-to-know compartmented intelligence level. We scrambled to relabel and reprint everything, incinerating all the old copies. Then we sent the report out. Each copy was numbered and delivered by courier, protected and accounted for from origin (me) to end user.

And I kept a copy of the distribution list, showing every numbered copy, who delivered each one, and who signed for it on the other end. Which came in handy when a copy went missing and they came looking for someone to blame. I think I can say that the FBI got involved, as it did at Mar-a-Lago, but by that point it was no longer my problem, because I was totally in the clear and on my way to a new flying assignment in Japan.

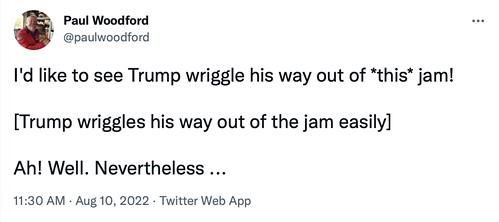

When it comes to classified material, you can’t be too careful. Unless you’re orange, that is, in which case this classic tweet applies:

I totally feel your pain with that initial incident.

And it always stuck in my craw that elected and appointed officials were never held to the same standard we, in uniform, were.

And I love the fact they changed that, even if it was a vengeful gesture.

And if they do manage to take him down for it, what a precedent for future Presidents, vice Presidents, Cabinet Members and Congressional members granted clearances for their position without nearly the vetting we had to go through. (let alone the training and continued training, and continued after training… And the threats…)

Security is a big deal and when it’s high level officials (POTUS, VP, SECSTATE) in whom foreign entities prize as targets, the consequences should be higher.

but that’s another rant.

Hope he rots in an orange jumpsuit (that matches his hair)

Couple of stories about the snake eaters I worked with at US Special Operations Command. Our boss in J3 was an Army colonel and a Ranger, which is some tough stuff, but he used to get to bragging as if he’d been a central player in every special op in memory. Foghorn Leghorn was our nickname for him. Some of the officers and NCOs I worked with were Delta Force and SEAL types and had actually been on those ops, but they kept their mouths shut around the colonel. One day, though, after the colonel left the room, I heard one of them say to another “What chalk was he on at Son Tay? I don’t remember seeing him there.”

Another one of the snake eaters was also an Army colonel, which I could never figure out because he looked so damn young, plus why, if he was a colonel, wasn’t he in charge of anything? Also, you couldn’t take the guy out in public because he couldn’t finish a sentence without “cunt,” “fuck” or “shit” in it. Found out later he was one of the Farsi-speaking operators sent in ahead of time to pass as locals while locating and surveying the physical facilities where the Revolutionary Guard held the American hostages (locations, which streets were best to use for ingress/egress, where guards were posted, which way the doors opened, even) and provide on-site help during Carter’s rescue attempt … then left in country after the disaster in the desert, on their own to find their way out, because any help in exfiltration would have exposed them and their part in the operation. The story was it took him almost a year to make it across the border into Turkey. And he never, ever, bragged about any of the things he had done … nor did the rest of them. I am still in awe.

I see kos also posted this one. From the 1970 line US Army pov all these glory seeking green beanie snake eater units are a waste of resources. We needed more guys in the forts and convoys and patrols than we needed Hearts and Minds. Nowadays it seems all these wet work units exist mostly to sell novels, tell alls and movie scripts. And leak operational intel like a BSA leaks petrol.

Cool you met Saburo Sakai, read his book. Soldiers, airmen, sailors, were routinely beaten and abused in Imperial Japan. Top down authoritarian brutal rule. Assassination of ‘leftist’ military or political leaders and terror tactics, largely successful, led Japan to become a military death cult. Becoming delusional about Japanese power and exceptionalism, biting off far more than it could ever digest or defend. A propensity for suicide is not a military virtue, after all. Their brutality towards captives and civilians riveled the Nazi Germans yet the Japanese were hardly held to task because we needed them to contain communism.

Tod recently posted…Tomorrow Belongs to Kyle Rittenhouse

Hope my tale sort of fits into this thread:

Wandering through an antique store in Astoria, OR recently I spotted a yellowed paperback for sale ($10) printed in 1961. The title immediately caught my eye: *Stuka Pilot* by Hans Ulrich Rudel, WWII nazi pilot detailing his air war on the eastern front. Forward by an RAF Group Captain and introductions by Rudel’s mother and father. A fair amount of b&w photos included. About 100 pages into the book, I googled Rudel and was shocked by his story; too good a story to abbreviate here, so please google him on your own. So far a good albeit challenging (a bit archaic) read.