“In late August 1619, a ship arrived in the British colony of Virginia bearing a cargo of somewhere between twenty and thirty enslaved people from Africa. Their arrival led to the barbaric and unprecedented system of American chattel slavery that would last for the next 250 years. This is sometimes referred to as our country’s original sin, but it is more than that: It is the source of so much that still defines the United States.”

— Nikole Hannah-Jones, The 1619 Project

The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story

The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story

by Nikole Hannah-Jones

![]()

A few months ago, after reading about a school district’s attempt to ban “Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You,” by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi, I borrowed a copy to read and review. The book turned out to be a children’s version of “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America” by Ibram X. Kendi alone, dumbed down to a cringe-inducing extent. I thought about reading the adult original, but decided instead to read and review “The 1619 Project,” created and edited by Nikole Hannah-Jones, which sits at the nexus of conservative grievances over teaching less-than-flattering aspects of American history, and is often confused with, and wrapped up in, what book banners and white-wing politicians refer to as “critical race theory.”

“The 1619 Project” is actually three things. The original version makes up the entirety of the August 2019 issue of The New York Times Magazine. It contains a history of slavery, several essays, and photos. Then there is the book version reviewed here, published in November 2021. It expands on the original with additional essays, short fiction pieces, and poems, with textbook-style annotations and citations, a bibliography, and an index. The third is a bit harder to pin down. It’s usually referred to with the hashtag #The1619Project, meaning the widespread adoption by schools and colleges of the award-winning project’s lessons on the suppressed history of slavery in the United States and its explanation of how that history is entwined with government, institutions, and society today.

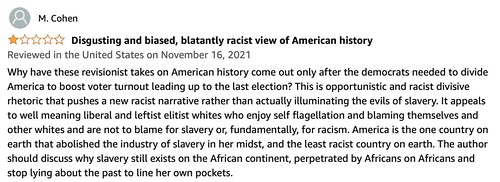

Critics abound, most of them claiming to be angry over Nikole Hannah-Jones’ and her 1619 Project contributors’ treatment of the founding fathers and Abraham Lincoln, but doubtlessly motivated by less worthy impulses. If it pains you to learn the great orator Patrick Henry, slave owner, he of “Give me liberty or give me death” hero-worship, warned state delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention that if they agreed to a federal militia and court system “They’ll take your niggers from you,” well, as Jeff Foxworthy might say, you might be one of these Amazon and Goodreads reviewers:

Surprisingly, to me at least, I was familiar with several aspects of Black American history outlined in “The 1619 Project.” Not that I learned any of it in school — no, nearly everything detailed here was written out of the textbooks I studied as a child (and even as a college student) — rather, I’ve absorbed new information in my general reading as an adult, particularly in the last 20 or so years.

One example: I learned about Lord Dunmore — the British Governor of Virginia who in 1775 enlisted an army of escaped slaves to fight against American revolutionaries with the promise he’d grant them freedom when the war ended — when I read M.T. Anderson’s young adult novel “The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Volume 2: The Kingdom on the Waves.” In fact I learned more about Lord Dunmore’s treachery from Anderson’s novel than I did from “The 1619 Project,” which fails to mention the part where, after the British defeat, Dunmore sold the surviving members of his “Ethiopian Regiment” to slavers in Jamaica where they were literally worked to death, that being the way white plantation owners treated slaves in that British colony.

This and other events in Black American history, though, tend to come our way in hit or miss fashion. Before I read it, I had no idea M.T. Anderson’s young adult novel would address the role Black slaves and freemen played in the Revolutionary War. Here, in “The 1619 Project,” Black American history is assembled in an annotated, academic, yet highly readable way: the history of slavery in the Americas, how it corrupted and influenced the founders and writers of our Constitution, the central role it played in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, how inextricably it remains woven into government, our institutions, and society today, from policing to economic inequality, to our still-segregated schools, to voting restrictions and the electoral college. “The 1619 Project” is essential reading, already in use as an educational tool by more than 4,000 teachers in all 50 states despite existing and proposed bans in red states.

Other links:

You may have heard book banners and anti-CRT politicians claim that academics and historians debunked “The 1619 Project,” forcing the editors of The New York Times Magazine to withdraw or repudiate the August 2019 issue. That is not even remotely true. Here is the actual letter to the editor critiquing “The 1619 Project,” along with the response from the editors of the NYT Magazine.

Also worth reading: Wikipedia’s description of “The 1619 Project” and summary of the controversies surrounding it.

An older (Feb 2021) Wonkette post about state-level efforts to ban the use of the 1619 Project and the Pulitzer Center’s curriculum based on it. Several other GOP-dominated states are by now doing the same.