You Can’t Read That! is a periodic post featuring banned book reviews and news roundups.

Textbooks confiscated from Tucson Unified School District classrooms, January 2012

Banned Books Week Commentary From Friends & Foes

Can you parse this Banned Book Week letter to the editor? I can’t make heads or tails of it!

An attempt to ban a book can be a good thing. It causes us to learn what it’s about; perhaps an idea. George Orwell’s ‘Animal Farm,’ completed in 1943, found that no takers among publishers due to its criticism of the U.S.S.R. Nobody dies from reading a banned book, or do they? Are you proud and excited because you’re reading a banned book?

Redstate: “Banned books” are a lie told by leftists to feel good about themselves.

Another letter to the editor: ALA’s use of the term ‘banned books’ seems a little disingenuous.

Slate Magazine: Banned Books Week Is a Crock.

Book Riot: Dear Slate: Banned Books Week Isn’t a “Crock.”

Jackie Delaney: Is Banned Books Week Still Necessary?

YCRT! News

New Jersey school district bans, then unbans, John Green’s Looking for Alaska. School superintendent, upon receiving a single parental complaint, overreacts by banning the book; later, after school district review, is forced to reinstate it. Looking for Alaska, an enormously popular young adult title, has been here before.

YCRT! Banned Book Review

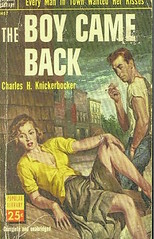

The Boy Came Back

The Boy Came Back

Charles Knickerbocker

The book:

The Boy Came Back is about characters in a Maine seacoast village during the Korean War. Most of the men of the town are veterans of WWII. They and the rest of the townspeople have had enough of war and are eager for peace and prosperity. The trouble in Korea, which keeps those who know they won’t have to go glued to the radio at Joe’s Beer Garden, is otherwise kept at arm’s length.

A young man with a history of juvenile delinquency, now a war hero from WWII, returns to town after a years-long absence. He has different names, but everyone calls him The Boy. He brings with him a wife. She too has a name, but everyone calls her The Girl. The Boy suffers from what is today known as PTSD. He gets in vicious fights but otherwise keeps to himself.

The Girl takes a troubled middle-aged man with a sexless marriage, Dr. Snow, under her wing (by which I mean she fucks him). The Girl’s act of mercy saves the marriage of Dr. and Mrs. Snow, and for them at least life improves. For everyone else, not so much. The village heavy, Lea, a small-town bully and the cause of many of The Boy’s problems in earlier life, goes after The Girl. The Boy kills The Girl, then Lea, then disappears.

The Boy Came Back is worth reading for its portrayal of American attitudes toward the Korean War alone; overall it’s engagingly written and stands the test of time. I don’t know how well it sold initially, but once it became notorious as the object of a book-banning witch hunt, I’m sure sales soared. Today it’s forgotten and out of print, and I had to search out a used copy from Amazon in order to read it.

The witch hunt:

The novel was published in 1951. At the time, Illinois’ state library program distributed books to rural communities through public schools. In October, 1953, a teenaged girl borrowed a copy of The Boy Came Back from the state library distribution point at her high school in Richland County. The girl’s mother read it, confiscated it, and turned it over to County Sheriff Jesse Shipley. The sheriff wrote a letter to Governor William Stratton urging that “the guilty persons be prosecuted and that the legislature conduct an inquiry into the matter.” The sheriff went on to condemn the book for its “communistic intent of attempting to lower the morality of American boys and girls.” The school superintendent of Richland County, Loren W. Cammon, also got involved, writing to the state librarian and including this description of the novel:

Without a doubt, it is the worst form of reading material I have ever seen in a high school. It is lewd in every sense of the word. I strenuously protest having such immoral reading material issued to the schools of Richland County.

Illinois state library personnel apologized, saying they made a mistake in including this adult novel in its shipment of books to the high school distribution point in Richland County. By then, though, the witch hunt was in full swing. In November, 1953, Illinois Secretary of State Charles Carpentier, presumably under orders from Governor Stratton, publicly rebuked Helene Rogers, the state librarian, ordering her to remove all “books of a salacious, vulgar or obscene character” from circulation. Other conservative politicians jumped on board, demanding the removal of “sex education” books from libraries and schools.

Rogers, noting that “if we acted on [the order] as it stands we would start with the Bible,” and without informing the state library advisory committee, began pulling all books not on a core list of suggested titles for library collections. By the time Rogers’ purge came to the attention of the press in December, 1953, she had removed between 6,000 and 8,000 books from state libraries, including popular novels by authors Sinclair Lewis, John Dos Passos, and Mickey Spillane.

In mid-December, 1953, Secretary of State Carpentier’s hometown newspaper, the Moline Dispatch, broke the story, which quickly spread. Illinois was held up to national and even international ridicule. The Washington Post called it “the Illinois Book Controversy.” Other papers, and some public officials, decried “witch hunting in the libraries.” Public opinion in the state turned against the book-banning, and the governor and secretary of state were forced to backtrack. Governor Stratton issued a clarification: while child readers should be “protected,” adults should be able to “read what they want.” Secretary of State Carpentier tried to lay the blame on state librarian Rogers, saying her “overzealous and wholesale withdrawal of hundreds of books from general circulation goes far beyond protecting school children in the selection of reading material, and has the tendency of making [my] original intention appear ridiculous.”

In January, 1954, Carpentier ordered Rogers to restore all the withdrawn books (including The Boy Came Back), but with this stipulation: he insisted Rogers “make it impossible for school children to obtain smut or objectionable materials from the Illinois State Library.” Rogers’ response was to stamp controversial books with the label “this book is for adult readers.”

Stamping books did not quell the controversy. Newspapers as far away as Great Britain carried news of the book stamping, one writing that “they are not burning books in the state of Illinois, they are putting ‘red flags’ on them.” In February, 1954, Carpentier said the incident had “turned into a comedy of errors,” and that he was “ready to climb the walls over this thing.” In March, 1954, on the day librarian Rogers was to appear before the state library advisory committee to answer questions about the book purge, she suffered a stroke and never was able to testify about her role in the scandal.

Echoes today:

Wow, things have certainly changed for the better, have they not? No, not really. Things haven’t changed much at all, and this is why I get mad when people suggest we no longer need a Banned Books Week in the USA.

One year ago, in 2014, Highland Park, Texas school administrators began red-flagging school library books and books used for class reading assignments that were not on an approved list of titles deemed “safe” for high school students to read. Regular readers of my YCRT! columns know that parental demands to red-flag or completely remove controversial books from school libraries and classrooms occur on a weekly basis in the USA. Regular readers also know that school administrators often cave to these demands, either placing books on restricted “parental permission only” lists or removing them altogether.

In February, 2015, the Kansas senate passed SB 56, which when signed into law will allow for the arrest, prosecution, and, if found guilty, imprisonment of teachers and school administrators found to have taught anything considered harmful to minors, including controversial works of literature. At this point it’s anyone’s guess what “harmful to minors” means.

In 2012, Arizona became a national and international laughingstock after banning textbooks, novels, and plays (including Shakespeare’s The Tempest) taught in Mexican-American studies classes, eventually backing down in embarrassment and reintoducing the banned books. Mexican-American studies classes are still banned in Arizona, I should note, derided and ridiculed by white supremacist Arizona politicians in the same McCarthyite terms used in 1953 to describe The Boy Came Back as communistic and revolutionary in purpose, pushing principles that lie outside Western civilization.

As for Illinois, state politicians and fearful civil servants still willingly engage in book-banning, witness the 2013 banning of the graphic novel Persepolis from Chicago public school classrooms and libraries, as well as a follow-on attempt to find and punish the teachers responsible for its adoption in the first place, a witch hunt ordered and carried out at the highest levels of Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration.

Differences between then and now? Not that many, it seems to me.

Reference Sources:

Okay amigo, I’ll take a shot at parsing the letter to the editor. It would be easy to say that the writer was using some of those opiates that kill but what I think was trying to be said was that if a book is banned people might look at why it was banned and think about that, that being a good thing. I think the writer also meant that while there is no reason to ban a book some books might just be crap and a waste of a mind to read. Myself, I’d rather just not finish a book that I thought was crap, speaking of which I’m putting down the He Who Killed the Dragon a Swedish crime novel that the late and unlamented TV series Backsromn was based on.

Burt, I agree, at least with regard to the first two sentences. But the rest of the letter seems to be arguing for something else. I don’t know what, though.