This all started when I posted a cool photo on Facebook:

When I posted that photo I didn’t bother to identify the nationality of the jet, but some of my friends wondered about it. Good question … what are those colors? I used to know those markings pretty well: the answer is Belgium.

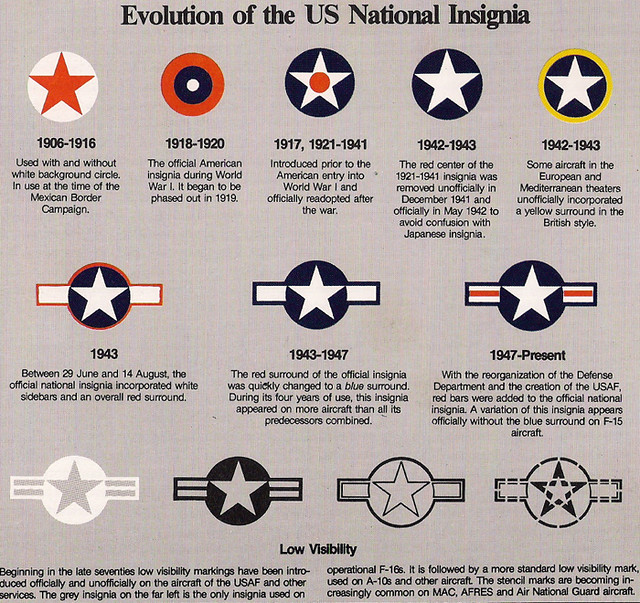

Then, two or three days later, a visitor at the Pima Air & Space Museum asked me about the stars & bars markings on American military aircraft. He knew they’d changed several times over the years and wanted to know if I had details. I didn’t, but I vowed to learn more about the subject in case anyone asks me again.

So this is about the different kinds of insignia US military aircraft have used over the years, and why we changed them when we did. I might do something on other nations’ insignia one day, but not now … this post is about American roundels and fin flashes.

Photo set #1: early days

This set takes us back to the beginning. The first photo shows a couple of US Army Signal Corps aircraft used in the 1915 expedition against Pancho Villa. Our national insignia then was a simple red star, the symbol adopted by the Soviet Union a few years later. When we started flying in WWI we switched over to British- and French-style roundels and fin flashes to better integrate with allied air forces. Our roundels and fin flashes were red, white, and blue, of course, but other than that they weren’t exactly standardized.

As shown on the SE-5 in the second photo of this set, the American British roundel was blue on the outside, then white, then red in the middle. The fin flash led with blue. But check out the roundel and fin flash on the Spad in the third photo. On American aircraft (photo #3) the order of colors on the roundel and fin flash is reversed. I’ve read that the first version was supposed to be for combat while the second was supposed to be for training, but I’ve seen photos of both versions on what appear to be combat aircraft. It must have been confusing for the French.

Update (11/10/14): Prior to America’s official entry into WWII, American volunteer pilots flew with the French, flying aircraft wearing French colors but with American squadron insignia. The Spad in the third photo is sporting French roundels and fin flash, along with what was to become the American roundel on the wheels, and an American squadron insignia on the fuselage. The roundel that survived WWI and stayed with us up to WWII is the last one, also displayed on the wings of the trainer in the fourth photo.

Photo set #2: fin flashes

|

|

The two photos in this set show US military fin flash schemes used during and after WWI. The fin flash in the first photo is the same one used during WWI. The fin flash in the second photo was adopted in 1927. Both types were used in the years leading up to WWII, but were eliminated after 1942.

Photo set #3: WWII to the present

This set of photos takes us through WWII to the present day. After Pearl Harbor, we eliminated the red circle in the middle of the roundel lest it be mistaken for the Japanese rising sun symbol. The new roundel, visible on the Bolo bomber in the first photo, was a dark blue circle with a white star in the middle. At the same time, however, studies were demonstrating that shape was more important than color in making out aircraft markings from a distance, so in 1943 we added bars to each side of the roundel, as shown in the second and third photos, first with a red border (introduced in May 1943) but later with a blue border (introduced in September 1943).

In 1947 we added a red stripe inside the bars on either side of the roundel, returning to the red, white, and blue color scheme. This roundel, shown on a Navy fighter in the fourth photo of the set, is the one we still use today, typically with a blue border but sometimes a black one.

Photo set #4: gratuitous F-15 photos & low-visibility markings

|

|

When I started flying the F-15 Eagle in 1978, it wore the same roundel introduced in 1947. The bright colors of the roundel, which you can see on the Eagles in the first photo … that’s me on the wing, by the way … were in marked contrast to the Eagle’s subdued gray paint scheme. Sometime in the late 1980s American combat aircraft began to be repainted with low-visibility markings, as on the F-15 in the second photo.

Update (8/25/16): This chart I found on Tumblr seems useful:

The roundel, and the fin flashes we used to use, identify American military aircraft, so they were and are common to all the services. Since some expert is sure to bring it up, yes, there were some (unimportant) exceptions in the past; USMC and Coast Guard aircraft once used unique service symbols in addition to the standard roundel. Borders of different colors, or no borders at all, have surrounded roundels, mainly depending on the color of the aircraft itself (the Navy, for example, used to paint all its aircraft blue, so there was no reason to use the standard blue border).

As the military was beginning to learn in WWII, recognizing the national insignia of aircraft is pretty difficult. Colors are hard to make out from a distance, and I don’t know that shapes are all that much easier. Generally, in a conflict, you rely on aircraft recognition: you learn the shapes of all the different aircraft you’re likely to see, friendly and enemy alike, so that you can ID them at a distance. Of course in a geographical area where different nations fly the same types of aircraft, you have to learn the national markings. In NATO, for example, the Brits and Germans flew the same F-4s we did; if you didn’t have radio communication with them, you had to get close enough to see the colors and markings before you knew who they were.

During the Cold War all Warsaw Pact nations flew Soviet aircraft. It was not inconceivable that in some future conflict we might be allowed to engage aircraft of one Warsaw Pact air force but not another; the only way to tell an East German Flogger from a Yugoslavian one was to get close enough to recognize the national markings.

When I flew in NATO at the height of the Cold War we had to know the roundels and fin flashes of all allied and Warsaw Pact nations. We memorized them and were tested a couple of times a year. When I flew in the Pacific a decade later, however, it wasn’t an issue. Sure, we knew the North Korean markings, but no one ever tested us on them, nor on the markings of any of the dozens of other air forces in our area of operations.

Today, with the prevalence of low visibility markings (since Desert Storm nearly all nations use them on combat aircraft), you have to close to within 1,000 feet of an unidentified military aircraft before you can make out the insignia. This is perhaps why we didn’t have to study national markings when I flew in the Pacific, because it was during and after Desert Storm when everyone went to subdued markings. Aircraft recognition and classified technical means are the way to identify nationality these days.

Some of the photos shown above are my own, taken at the Pima Air & Space Museum. The volunteers who restore these aircraft always make sure they get period markings correct, as they do at any good aviation museum, so visiting an exhibit like ours is a great way to study the evolution of military insignia.

Links

There’s a picture of the Seaplane Tender USS AV-5 Albemarle with a Martin PBM Mariner on it’s fantail. If you look at the picture the star is black. Did at any time during WWII 1943 were black stars used?

I have seen the photo and can’t explain it. No wartime chart or listing of US military aircraft markings of WWII lists a black star. Can any readers help? p.s. Link to photo: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/89/USS_Albemarle_%28AV-5%29_off_Norfolk_1943.jpg

Great post. Of course the S Vietnamese airforce used our star-with-bars roundel with yellow added. Odd that North Vietnam also used the same star-bars design roundel only with a yellow star on a red field, with side-bars also in red. Always thought the euros were pushing their luck with roundels that look so much like shooting sports targets.

‘Tod’ recently posted…ERCO Ercoupe Light Sport Aircraft: Antique Flying Art