I haven’t blogged about flying for more than a month. Why? Ironically, it’s because I’ve been up to my eyes in a flying-related project, a presentation on the F-15 Eagle I’m giving to Pima Air & Space Museum volunteers and staff in a few days. Today, though, I need a break, so I’ll step back from research and Powerpoint slides to write about aerial gunnery and towed targets.

I haven’t blogged about flying for more than a month. Why? Ironically, it’s because I’ve been up to my eyes in a flying-related project, a presentation on the F-15 Eagle I’m giving to Pima Air & Space Museum volunteers and staff in a few days. Today, though, I need a break, so I’ll step back from research and Powerpoint slides to write about aerial gunnery and towed targets.

Aerial gunnery and towed targets. Doesn’t sound like much, but it’s the most fun thing you can do in a fighter in peacetime. Practice firing air-to-air missiles at drones isn’t something any of us got to do often. I did it three times during my entire F-15 career, and I expect that’s typical. Missile shoots, in my case, involved deploying halfway around the world to Eglin AFB in the Florida panhandle, then firing at unmanned drones over the Gulf of Mexico, always a huge production. Gunnery practice, though, was something we could do from our home bases at the nearest bombing range. I can’t count all the times I’ve fired my 20mm cannon at darts and other towed targets, but every time was a blast.

My first aerial gunnery experience was over the Gila Bend Range (now the Barry Goldwater Range) in southern Arizona in 1978, and was the very last mission of my F-15 training at Luke AFB. Our flight consisted of three F-15s: the target tow and then a two-ship with me and my instructor pilot. We flew south to the range, checked in, did a visual sweep of the ground below to make sure there weren’t any unauthorized people down there, and got clearance to fire from range control. The tow pilot unreeled the dart to the end of its 1,500-foot steel cable and entered a 3-4 G descending spiral. I made two or three firing passes on the dart with my instructor in chase (watching me to make sure I aimed at the dart, not the tow).

I had to score at least one hit in order to graduate. I fired all 940 rounds from my cannon, my instructor called “knock it off,” the tow pilot went back to straight and level flight, and my instructor slowly closed in on the dart to count my score. I don’t know if I really hit the damn thing or not … I wasn’t allowed to fly alongside the dart to look for myself … but my IP said there was a single hole in one of the dart’s wings, and thus I graduated from F-15 training. One round out of 940. In time I got better.

The dart I shot over the Gila Bend Range was like the one in this photo: about 20 feet long, made of wood and aluminum. They had flat reflective surfaces so that you could track them with with your radar; they could be towed by any fighter aircraft in the inventory. The one in the photo is suspended under the wing of an F-86 … that’s how we did it at Kadena AB in Japan in the early 1990s, where we used a private contractor to tow darts with civilianized F-86 fighters from the Korean War era, shooting at them over the Sea of Japan. In Europe we fired on darts over the North Sea. In Alaska, as at Luke AFB in Arizona, we conducted aerial gunnery over land on a dedicated bombing range.

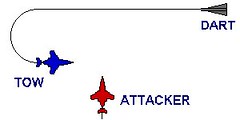

Towed targets, when you’re firing on them, are never straight and level. As with my first gunnery mission in Arizona, tow pilots fly tight 3-4 G descending spirals at about 450 knots; consequently so does the dart, 1,500 feet behind the tow, simulating an enemy fighter in maneuvering flight. The setup is depicted in the inset drawing: you start with a lot of angles on the dart, basically dogfighting to stay behind it while reducing your angle-off to between 30°-40°, then working your angles down to about 20° as you close to within 1,000 feet and open fire. You want to fire with 10°-20° deflection, but never less than 10°, because if you’re dead behind it and hit it just right, it’ll come apart and you’ll fly through the debris. A buddy of mine did just that in Alaska one day … he came home on one engine with dents and gouges all over his jet. He claimed he’d kept his angles up, but his gun camera film showed him right in the plane of the dart with no angle-off, and when the dart came apart he flew right through the chunks of metal and wood … it happened so fast he couldn’t get out of the way.

Towed targets, when you’re firing on them, are never straight and level. As with my first gunnery mission in Arizona, tow pilots fly tight 3-4 G descending spirals at about 450 knots; consequently so does the dart, 1,500 feet behind the tow, simulating an enemy fighter in maneuvering flight. The setup is depicted in the inset drawing: you start with a lot of angles on the dart, basically dogfighting to stay behind it while reducing your angle-off to between 30°-40°, then working your angles down to about 20° as you close to within 1,000 feet and open fire. You want to fire with 10°-20° deflection, but never less than 10°, because if you’re dead behind it and hit it just right, it’ll come apart and you’ll fly through the debris. A buddy of mine did just that in Alaska one day … he came home on one engine with dents and gouges all over his jet. He claimed he’d kept his angles up, but his gun camera film showed him right in the plane of the dart with no angle-off, and when the dart came apart he flew right through the chunks of metal and wood … it happened so fast he couldn’t get out of the way.

But yeah, unlike practicing with air-to air missiles, where you have to deploy to one of only two or three ranges in the USA where live missile shots are allowed, where expensive unmanned drones have to be prepared and launched, practicing aerial gunnery with towed targets is dirt simple. Darts, at least the old aluminum and wood ones, were made locally to standard specifications, tow rigs could be suspended under the wing of any fighter, and as long as you had a gunnery or bombing range nearby you could practice aerial gunnery whenever you felt like it.

Scoring was as primitive as it gets: you literally flew up alongside the dart afterward and counted the holes. When done you cleared the tow pilot to cut the cable, and the dart, with its 1,500 feet of cable attached, would fall away. I remember seeing hundreds of old darts on the ground at the Gila Bend Range. Most of them were in pieces but some, like the one in this photo, were relatively intact. Sometimes you’d hit a dart near the front and the aluminum would peel away, leaving only a 20-foot stick wobbling at the end of the cable. Sometimes, as the tow pilot unreeled the tow cable at the start of the mission, the dart wouldn’t fly right and it would have to be cut away and the mission scrubbed. Sometimes the cable wouldn’t cut after the mission and the tow pilot would have to jettison the entire towing rig. But generally darts worked just great, as simple things so often do.

I don’t know if the old wood and aluminum darts are still used today. I expect not. Even in the 1970s the USAF was beginning to use more complex towed target systems like the one in the photo above, mounted underneath a Japanese F-15. The small red torpedo-looking object is an acoustically scored towed target. The big white pod above it houses the tow cable and motor. The tow target unwinds to the end of a 1,500-foot cable (just like the old standard dart) and then unfurls a long orange cloth banner behind. As attackers fire at the banner sensors in the target forebody, the little red pod, count rounds that whiz by within “hearing” range. I’ve fired on these types of towed targets a few times, and they’re not nearly as satisfying as the old darts. You aim at the orange banner, not at the forebody itself, which is tiny and hard to see. The tow pilot tells you whether you scored or not; the banners sometimes fall away but otherwise you don’t see the results of your gun work. The old darts sparkled when you hit them and sometimes rewarded you by disintegrating in mid-air … these acoustical abominations just keep flying, as if to say “screw you.” When the mission’s over the pilot doesn’t cut them away. They’re too expensive for that, so they’re reeled back in and flown home. Unless you managed to hit the forebody itself, that is. As small as it was that took some doing … but you can bet we always tried.

Speaking of cables not cutting free, I had a friend at Soesterberg who once towed dart over our North Sea range for two Bitburg-based F-15s. One of them shot the dart off the end of the cable, ending the live fire exercise. My friend cut the cable, then asked the lead F-15 to fly alongside and confirm the it was gone. The F-15 pilot closed in, radioed that the cable was gone, and cleared my buddy to fly back to our base in the Netherlands.

The Dutch commander of Soesterberg Air Base was having a garden party at his house off the end of the runway. As he carried a tray of jenever to his guests, a single F-4 flew low overhead with its landing gear down, lined up on final approach. Suddenly a massive old-growth tree near the table where his guests were sitting jumped into the air and shot off sideways at 230 kilometers an hour. The steel cable, all 1,500 feet of it, was still attached to the tow rig under my friend’s wing. Everyone at the party was covered in grass and clumps of dirt, but no one was hurt and they all had a hell of a war story to tell afterward. My friend, formerly known as Deadeye, was forever after known as Snag.

I was going to end there, favoring going out on a light note, but I have one final photo to illustrate the reason fighter pilots practice aerial gunnery in the first place. I don’t know what kind of fighter the attacker is flying … I’m told it’s a US Navy F-18 … but I know what the target in the gun reticle is, and I’m sure you’ll recognize it too. Guns kill on the Fulcrum!