You Can’t Read That! is a periodic post featuring banned book reviews and news roundups.

YCRT! Editorial

The American Library Association’s Banned Books Week is Sep 22-28. Every year conservatives challenge the ALA’s use of the word “banned,” claiming that no books are banned in the USA. I’m not sure what the ALA’s official response to that claim is, but I too get challenged when I use the word, and this is my response:

I find I have to explain my use of the word “banned” every few YCRT! posts. My position is that any time someone tries to keep someone else from reading a book, the intent is to ban … even if the ban applies only to one sixth-grade classroom in some rural town.

The US Post Office once banned novels like Tropic of Cancer. Conservatives of the day advanced the argument that such books weren’t really banned, because you could always hop on an ocean liner, go to Paris, and buy copies there. Conservatives today recycle the same argument: you can still buy copies of Captain Underpants or Heather Has Two Mommies at Barnes & Noble, so what’s the problem?

The problem is that some people want to prevent other people (often kids, but not always) from reading these and other books. They can’t prevent B&N from selling copies, but they’ll do whatever they can to get books they don’t like removed from school libraries and reading lists. There’s only one verb for what they want to do. That verb is ban. There’s only one adjective for books that have been removed from school libraries and reading lists. That adjective is banned.

But fine, if you don’t value my opinion, here’s what Merriam-Webster says about the word “ban”:

… to prohibit especially by legal means <ban discrimination>; also: to prohibit the use, performance, or distribution of <ban a book> <ban a pesticide>

And under examples, they include this:

The school banned that book for many years.

I rest my case. Until the next time.

YCRT! Banned Book News

Great essay on banned books by teacher & writer David Lomax. I encourage you to click through and read the whole thing, but here’s an excerpt: “In twenty-three years of teaching English at the high-school level, I must admit that I’ve managed to get away with a lot. Students in my classes have read swear words, graphic depictions of violent and sexual acts, and been presented with characters whose values were radically different from their own. They have, of course, also been introduced to beautiful prose, vibrant characters, compelling plots and wide new vistas. In short, they have read literature.”

Fairytales banned? Oh yeah, all the time! But you knew that, right?

Here we go again. Another school year, another attempt to ban a book.

Meg Medina, an author who wrote a young adult book about bullying titled Yaqui Degado Wants to Kick Your Ass, was invited … then disinvited … to speak to a middle school class. Oops, make that cl*ss.

“Mary I handed out a printing monopoly on May 4, 1557 to the London Company of Stationers. In return for a lucrative monopoly of printing everything in England, the company would agree to not print anything the Crown’s censors deemed politically insubordinate.” I didn’t know copyright law started out as a form of censorship. This article makes that case that it still is. And here’s an up-to-the minute example!

In a previous YCRT! post I mentioned Dan Kleinman, an anti-ALA activist who crusades against what he claims is rampant and pervasive viewing of porn on public library computers. In my experience, libraries block internet porn with filters. Here’s an article from the Electronic Frontier Foundation claiming that not only do libraries filter, they take internet censorship to extremes.

YCRT! Banned Book Review

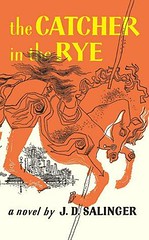

In honor of Banned Books Week, I read and reviewed a modern American classic, a novel that’s been on every annual banned books list since its publication, J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye.

The Catcher in the Rye

The Catcher in the Rye

J.D. Salinger

![]()

Holden Caulfield kills me. He really does. He’s a goddamn mess, that’s what he is. I hate him. You know what really annoys me? When you read a book as a kid and then read it again a hundred years later and the crumby thing holds up.

I read The Catcher in the Rye as a teenager in the early 1960s. I never bothered to check the publication date; for 50 years I believed it came out just about the time I first read it. I was wrong: Salinger wrote it just after WWII; it was published in 1951. It had been an instant best-seller and was already an established classic by the time my rebellious schoolmates and I read it.

My primary reason for re-reading Catcher in the Rye was to learn why it’s such a controversial book, why it so infuriates the book-banning crowd. I didn’t expect to enjoy the experience: I assumed I’d outgrown the book in the same way I outgrew Kerouac’s On the Road, which I thought life-changing as a 14-year-old but squirm-inducingly embarrassing as a senior citizen.

As it turned out, I loved reading Catcher again. Though I no longer share Holden Caulfield’s teenaged angst and alienation, I still feel for him. He doesn’t come across as some historical artifact, but as a flesh and blood kid, vivid and fresh, totally believable. Which, I guess, validates what I earlier said about assuming the book had just come out in the early 1960s when I initially read it. Even though Holden’s story takes place in the 1940s, a reader in the 1960s could be convinced Holden was a contemporary, and even today, in 2013, Holden feels part of the here and now.

I remember being struck by Holden’s swearing when I read the book as a kid. My classmates and I used the same language (and worse), but seeing it in print was shocking … and liberating. Curiously, I remembered Holden saying “fuck” on almost every page, but that turned out to be another false memory. The word doesn’t appear until the near the end of the novel, and then only in the context of Holden deploring the fact that some unknown vandal has carved “fuck you” into the wall of a stairwell at his little sister’s school. What Holden does say, and say often, is “goddamn,” “bastard,” “bitch,” and “hell.” That’s mild language by today’s standards, but it doesn’t date the novel … you feel like you’re listening to a troubled but essentially polite and well-bred young man, someone who’d open up in a private conversation with a friend but never cuss in front of strangers. The language doesn’t come across as quaint or outdated, and that’s another reason the novel holds up.

As with the swearing, I remembered Holden talking about sex more than he actually does. He thinks about girls all the time but he’s a virgin, and the one opportunity he has to get it on with a room-service prostitute, he’s too shy to do anything and pays her to put her clothes back on and leave. He worries that the girls he knows will succumb to his older, more experienced, classmates’ advances. He’s aware of the existence of homosexuals and disdains them. That’s as explicit as Holden ever gets about sex; what little he does say about the subject is abstract and non-pornographic.

So why does Catcher in the Rye push so many blue-nose buttons? It’s hard to believe, but as recently as 2005 Catcher could still make the American Library Association’s top ten list of challenged and banned books. When parents demand school administrators pull the book from library shelves and English class reading lists today, they cite Holden’s language and vague talk about sex. They also cite his smoking and drinking, his lack of religious faith, his poor study habits, his overall negativity. They don’t think he’s a good model for their kids. I suspect that somewhere in there is some rural resentment of snobby upper-class New York City folks. That pretty much sums it up: they don’t like Holden Caulfield and therefore they don’t want anyone reading what he has to say. Maybe they’re afraid their kids will feel as validated and liberated as I did when I met Holden in 1962.

You know what, though? Even though it’s one of the most challenged, banned, and censored novels ever taught in American high schools, The Catcher in the Rye is at the same time one of the most-taught novels in American high schools, a beloved book to millions, a classic.

Holden Caulfield’s still out there somewhere. I hope he didn’t grow up to be just another goddamn phony. That would kill me, it really would.