When I lead visitors on walking tours at the Pima Air & Space Museum, we start underneath a replica of the 1903 Wright Flyer. I think about Orville and Wilbur often. They showed us the way, and the F-15 Eagle I flew in the US Air Force used the same three-axis controls the Wrights developed back in 1903.

I like to remind museum visitors that while the Wright brothers were indisputably the first to achieve controlled, powered, sustained heavier-than-air human flight, they had plenty of competition. From the last years of the 1800s and into the early years of the 1900s, inventors around the world were chasing the same dream.

The Wrights’ great insight was the necessity for control. For an aircraft to be practical, it had to be able to climb and descend and to turn left and right. In 1901 and 1902, when the Wrights were experimenting with pitch, yaw, and roll control on manned gliders, Octave Chanute, an early collaborator and friend, paid several visits to their camp at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Shortly afterward he published information about the Wright’s early successes and methods of control. This gave the Wrights’ competitors the essential insight they hadn’t come up with on their own, and they redoubled their efforts.

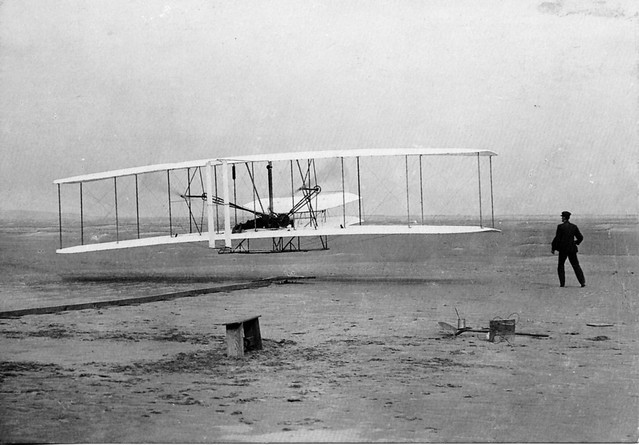

On December 17, 1903, when the Wrights flew their first powered aircraft at Kitty Hawk, they were at the controls of a fully maneuverable aircraft. That they couldn’t maneuver it very well was not a show stopper. The first flight, with Orville at the controls, lasted only 12 seconds and covered just 120 feet, but the fourth and last flight of the day, with Wilbur at the controls, lasted 59 seconds and covered 852 feet. The Wrights returned to Kitty Hawk during the winters of 1904 and 1905, testing improved versions of the original Flyer. In 1905 they were achieving flights of a half-hour and longer, flying figure-8 courses of 24 miles.

Oddly, the brothers didn’t fly between 1905 and 1908 … they sat on their world-changing invention. In 1908 they started flying again. Orville demonstrated a Flyer to the US Army (and huge civilian crowds) in Washington DC, and Wilbur shipped a second Flyer to France, where he flew for the public and European heads of state.

Wright Flyer I (1903): single engine driving two propellers by chain, lateral control by wing warping and rudder, forward mounted elevator for pitch control. Max speed about 30 mph, altitude 30 feet.

The Wrights, though they carefully documented their early flights with witnesses, records, telegrams, and photographs, didn’t go public until those 1908 demonstration flights. That was when they were finally acknowledged as the first to fly, becoming household names around the world.

The Wrights had been raised by their preacher father to be distrustful of outsiders. They were also methodical and cautious, and well aware of their competition. They filed for a patent after their initial success in 1903 and it was approved in 1906. The patent, most importantly, detailed their three-axis control system, consisting of a rudder for yaw, wing warping for roll, and an elevator for pitch.

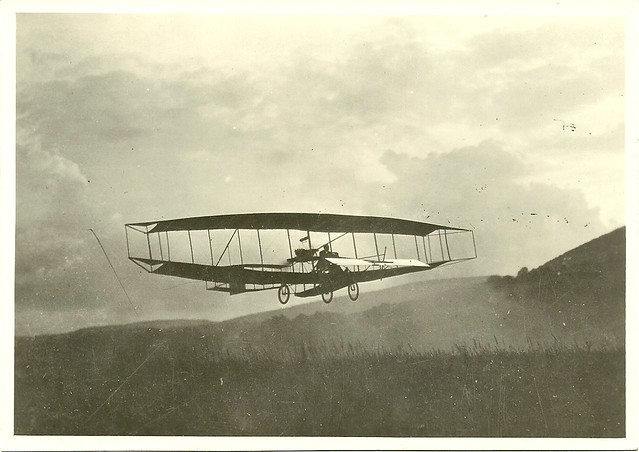

By 1908, when the Wrights finally began demonstrating their airplanes in public, others were flying too, notably another American pioneer, Glenn Curtiss. Curtiss, prompted by the information about the Wrights’ control system published by Chanute a few years before, designed and flew the June Bug in the summer of 1908. He won an early air race in Europe and then began putting on public demonstrations in America at automobile races, forcing the Wrights to hire and train pilots and start an exhibition team of their own.

Glenn Curtiss in the June Bug (1908)

Curtiss used ailerons rather than wing warping to control roll, but the Wrights had mentioned ailerons as an alternate to wing warping in their original patent application, so they had valid grounds to sue. And sue they did.

The brothers filed a patent infringement suit against Curtiss in 1909, and in 1913 they won. They had also filed lawsuits against other aviation pioneers overseas, but these were slow-rolled by courts in Europe. When WWI started, aircraft-manufacturing nations agreed to suspend aviation patent lawsuits and enforcement for the duration. By the time WWI ended, Wilbur was dead and Orville had sold the Wright Company to others. The lawsuits were not taken up again after the war.

Would the Wright brothers, had all their patent infringement lawsuits been successful, and if WWI had not come along, have been a brake on early aviation progress?

One can argue that they might well have been. The brothers were stodgy and cautious, and the last Wright aircraft built (the Model L in 1916) was not visibly all that different from the first Flyer flown at Kitty Hawk. In Europe, far more modern aircraft were being built, and of course aviation advanced by leaps and bounds during WWI, far outclassing anything the Wright Company ever built.

The Wright brothers, heroes in 1908, were by 1913 widely regarded as obstacles to progress. The patent wars kept the US aviation industry stagnant. The brothers’ preoccupation with lawsuits may have stifled their work on new designs, and by 1913 Wright aircraft were clearly inferior to those of European makers. When US pilots entered World War I they had no choice but to fly French machines.

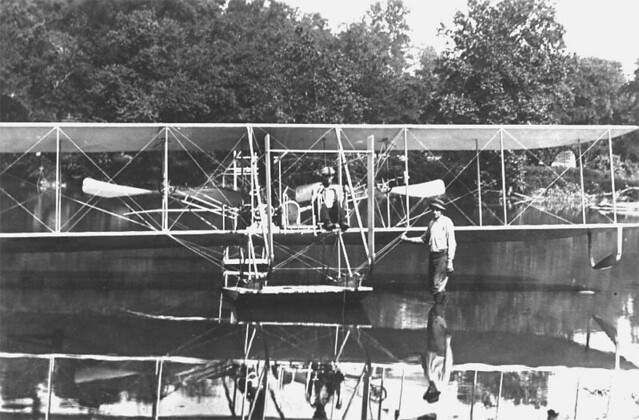

A picture is worth a thousand words, right? Here are two representative aircraft built by the Wright Company in 1913, just one year before the start of World War I, the Model CH and the Model F. It’s instructive to compare these photos of later Wright aircraft with the photo of the original Flyer, above:

Wright Model CH (1913): elevator has been moved aft, but overall the aircraft is very much like the original 1903 Flyer I (single engine, twin chain drive propellers, lateral control by wing warping and rudder). Max speed about 60mph, altitude unknown but probably in the 500-1,000 foot range.

Wright Model F (1913): built under license by the Burgess Company for the US Army. First Wright aircraft with a fuselage and “conventional tail,” but the wing and engine/propeller configuration is almost identical to that of the 1903 Flyer I, as is the method of lateral control by wing warping and rudder. Speed and altitude capabilities unknown, but probably similar to the CH.

By way of contrast, here’s a photo of an Avro 504, a British fighter introduced that same year:

Avro 504 (1913): the direction flight was taking overseas (Britain in this case), independent of the Wright brothers. A recognizably “modern” aircraft with aft elevator and rudder, ailerons for roll, and a forward-mounted engine. Max speed nearly 100 mph, altitude 13,000-16,000 feet.

This is just idle speculation. Once man started flying, the pressure to build more and more capable aircraft became irresistible, and lawsuits or no lawsuits, the nascent American aviation industry would eventually have rebelled against the Wrights and scrambled to catch up with the Europeans.

Here’s one more story to help illustrate the Wrights’ combative mindset:

When the Wrights sued Curtiss in 1909, Curtiss fought back by “proving” that another early aviation pioneer, Professor Samuel Pierpont Langley, a former secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, could have beaten the Wrights to the punch.

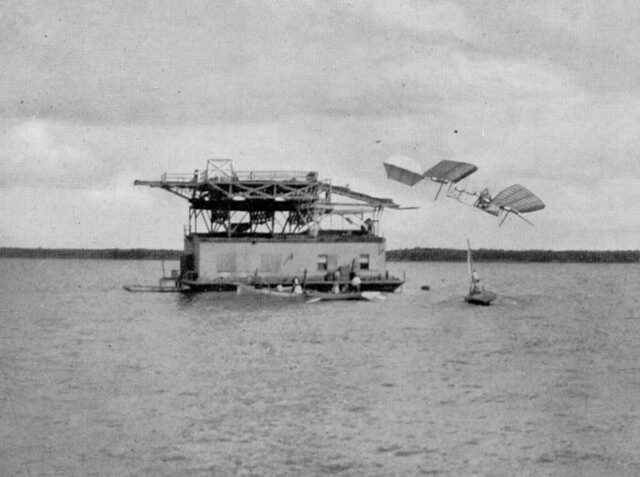

Langley’s attempts at flight were spectacular failures. His aircraft, the Aerodrome, was basically an unflyable piece of shit. It had no pitch or yaw controls, and in the unlikely event it did fly, it would have been unnavigable, totally at the mercy of winds, updrafts, and downdrafts. In October 1903 and again that December, Langley tried to launch the Aerodrome from a rail atop a houseboat on the Potomac River near Washington DC. Both times it pitched down and flopped into the water.

Langley’s Aerodrome going into the drink, Oct 1903

Since Langley’s Aerodrome did not infringe on any Wright patents, Curtiss set out to prove that the Aerodrome could have been successful, planning to argue later that his June Bug was more the descendant of Langley’s Aerodrome than of the Wrights’ Flyer. He rebuilt Langley’s wrecked Aerodrome but cheated by adding movable airfoils to control pitch and yaw. He successfully flew the modified Aerodrome for a short distance in 1914.

The flight didn’t affect the ruling in the patent lawsuit, but did result in the Smithsonian putting the Aerodrome … which was, after all, the invention of the Smithsonian’s former head … on display, along with a placard stating that it was the first heavier-than-air manned powered aircraft “capable of flight.”

By then, of course, Wilbur Wright, who had been the lead brother in the patent lawsuit, was in his grave, but Orville carried on the legacy by starting a a decades-long feud with the Smithsonian. Claiming — rightfully — that the Smithsonian had misrepresented aviation history and the Wrights’ achievements, Orville donated the original 1903 Flyer to London’s Science Museum. The dispute didn’t end until 1942, when the Smithsonian finally admitted that Curtiss had modified the original Aerodrome, and recanted its claim that Langley’s machine was capable of flight. Even so, the Wright Flyer remained in London until 1948, the year of Orville’s death, when it was finally shipped back to the USA and put on display at the Smithsonian.

Links:

Now this is interesting stuff. We rarely think about things like the law suits retarding progress. I think it largely has to do with the fact that it wasn’t the sort of thing covered in what would have been the media at the time.