“It’s like there are these words, they’re out there in the world, and you start wondering what it would be like to say them. Words have their own power — they create the feeling, just by the fact of your saying them.”

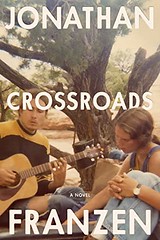

— Jonathan Franzen, Crossroads

Crossroads (A Key to All Mythologies #1)

Crossroads (A Key to All Mythologies #1)

by Jonathan Franzen

![]()

Some of what follows I’ve paraphrased from reviews of two previous Jonathan Franzen novels, “Purity” and “The Corrections”:

Some of the literary types I follow on social media disapprove of Jonathan Franzen. Perhaps he said something incorrect; I’ve seen popular opinion turn against other authors for such things, Joyce Carol Oates and Margaret Atwood among them. I don’t know what Franzen said to start all this, but I think he’s one of our very best contemporary novelists, a writer of Great American Novels. I love his work. He writes about ordinary people living what from a distance look like ordinary lives, but which, through his eyes, become extraordinary … and extraordinarily fascinating. Franzen narrates his stories in an old-fashioned third-person omniscient voice, looking inside his characters to reveal their innermost thoughts, fears, and motivations. In the process he creates real people … people like you and me, people we recognize and care about. People real enough to make us squirm in embarrassment, real enough to make us cry. Franzen’s characters become so real, in fact, that when they frustrate you, you sometimes shout at them because you know they’re right there, separated from you only by artificial barrier of paper and ink, and they might just hear you if you shout loud enough.

The Hildebrandt family of “Crossroads” is almost close enough to hear our shouts, too, even though additionally separated from us by time (the action in this novel takes place in the early 1970s), but for me at least it’s a familiar time, still fresh in memory.

I was struck by the prominent place of church and religion in the lives and minds of the Hildebrandts, because when I was a young adult in the early 70s, slightly older than Russ and Marion’s oldest child, Clem, I would have said religion played no part in my life, so I looked into an interview Merve Emry conducted with Franzen in September 2021 (link), where Franzen talked about the “enduring ethical function” of novels and offered this:

“I have been thinking a lot about the inescapable nature of religion. Even if it is uncoupled from transcendent beliefs or metaphysical structures, everyone still organizes their life around something that can’t be proved. I would say this goes particularly for the virulent atheists. It had been building in me for a long time, a wish to write about the fundamentally irrational basis for everything we think and do and espouse.”

As one of Franzen’s virulent atheists, I absolutely buy what he’s saying. It explains why the prominent place of church and religion in the lives and minds of the Hildebrandts did not in the least discomfit or alienate me. I understood and deeply related to almost every character: Russ, Marion (Franzen could have written a novel about her alone and it would have been enough!), Clem, Becky … even Perry, who rendered me frantic with anxiety. I know these people. And I can’t get enough of them.

There will be two additional novels about the Hildebrandts, should Franzen live long enough to write them (and he’d better, being 13 years younger than me), under the overarching title of “A Key to All Mythologies.” I’m waiting.

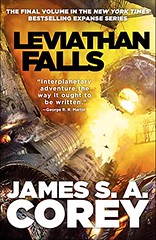

“The stars are still there,” she said. “We’ll find our own way back to them.”

— James S.A. Corey, Leviathan Falls

Leviathan Falls (The Expanse #9)

Leviathan Falls (The Expanse #9)

by James S.A. Corey

![]()

My rating for this novel, “Leviathan Falls”: 4 stars.

My rating for “The Expanse” series (novels and TV adaptation): 4.5 stars.

I was a third of the way into Neal Stephenson’s latest on November 30th when “Leviathan Falls” appeared on my Kindle. I thought I’d be able to put off reading it until finishing the other, but after two days realized I’d been reading the same page of “Termination Shock” over and over. I put the Stephenson aside and opened “Leviathan Falls.”

I grew up on hard science fiction. It’s still my first love. I almost always have wave-the-bullshit-flag moments with science fiction; I’ve had only one or two in nine novels and five televised seasons of “The Expanse.” This series of novels (and its television version) is hands down the best science fiction I’ve read or watched, consistently excellent and believable throughout.

Prior to the release of “Leviathan Falls,” I re-read the first eight novels of “The Expanse.” Originally, I rated the overall series at 4 stars. After finishing the ninth and final novel, with its engrossing and ultimately uplifting ending, I’ve raised my overall rating to 4.5 stars.

This individual novel, the brilliant ending notwithstanding, is in my estimation not the best novel of the series, and I rate it a little lower than the series as a whole. Some chapters — the ones describing the inner torments of Naomi, Jim, and Amos — were maudlin and drawn out. They struck me as padded, as if the authors wanted to keep the page count of this novel consistent with earlier ones.

But the ending! People will be talking about it for years. I think it’ll spark a huge demand for a continuation of the TV series, which apparently will conclude with the defeat of Marco Inaros in the Sol system, cutting out the bulk of the Laconia saga.

p.s. Before anyone reads too much into my ratings, check the ratings of the 900+ books I’ve reviewed on Goodreads to date. There are only four with five stars. I don’t give those out for anything less than perfection.

“It was about eleven o’clock in the morning, mid October, with the sun not shining and a look of hard wet rain in the clearness of the foothills. I was wearing my powder-blue suit, with dark blue shirt, tie and display handkerchief, black brogues, black wool socks with dark little clocks on them. I was neat, clean, shaved and sober, and I didn’t care who knew it. I was everything the well-dressed private detective ought to be. I was calling on four million dollars.”

— Raymond Chandler, The Big Sleep

The Big Sleep (Philip Marlowe #1)

The Big Sleep (Philip Marlowe #1)

by Raymond Chandler

![]()

Finally got around to Raymond Chandler’s classic detective novel “The Big Sleep.” It was a rewarding experience, seeing where so much of detective fiction got its start.

Maybe not you, but I’ve always been fascinated by Los Angeles at the beginning of the modern age: the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. I’ve devoured the historical noir fiction of James Ellroy and kept a sharp eye out for period detail in the movies adapted from his books, as well as television shows like “Bosch,” which in its second season featured flashbacks to a crime that took place in downtown LA in the early 1930s. It’s all here in “The Big Sleep”: the locations, the beginnings of the suburbs, the beach colony of Malibu with its wide open spaces, the Red Car, the mean streets.

Along with it, antiquated attitudes toward gays and Jews, a distinct lack of Blacks and Latinos, and crimes that would be considered quaint today, if not actually legal: nude photos, pornography, gambling.

But Philip Marlowe, his overactive Jewdar and homophobic opinions aside, is the real deal.

BTW, readers with an interest in historical LA and “The Big Sleep” will enjoy this online photo essay: Philip Marlowe’s Los Angeles: Tracking Down The Real 1930s Locations of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep.

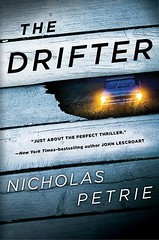

“For a soldier who’d spent eight years at war, not owning a weapon was like a writer emptying his house of pens.”

— Nicholas Petrie, The Drifter

The Drifter (Peter Ash #1)

The Drifter (Peter Ash #1)

by Nick Petrie

![]()

A friend, knowing what a fan I am of Lee Childs’ Jack Reacher novels, recommended Nicholas Petrie’s Peter Ash series, so I decided to start with the first book, “The Drifter.”

The concept is roughly the same. Although Peter Ash is more relatable than Jack Reacher, his instinctual ability to anticipate his foe’s next move in a fist-, knife-, or gunfight, coupled with his own mastery of the skills required in same, make him as lethal an ass-kicker as Jack. So that’s good!

As with a few other reviewers, I felt the ending of this first novel was a bit compressed and that a few threads were left hanging. I’m impressed enough to plunk down nine bucks for the Kindle version of the second novel, “Burning Bright,” and hope the series will get even better as Petrie develops his character.

“So she looks in her rearview mirror,” one is saying, “and there’s a bear in the back seat, eating popcorn.” When wildlife officers gather at a conference, the shop talk is outstanding. Last night I stepped onto the elevator as a man was saying, “Ever tase an elk?”

— Mary Roach, Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law

Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law

Fuzz: When Nature Breaks the Law

by Mary Roach

![]()

I’ve always loved Mary Roach’s writing, her knack for picking subjects curious readers want to know more about, and her infectiously enthusiastic approach to satisfying that need. Generally I rate her books at four stars, pretty much my top rating. This one was a three because it didn’t hold my interest.

Maybe it’s me. I thought I’d be interested in all the ways the lives of flora and fauna impact those of humans, but I just wasn’t. This book, compared to Roach’s earlier ones, seemed more full of facts, statistics, and numbers than usual (how many acres of this, the percentage of tiger attacks involving children rather than adults, the annual budgets of state fish and game agencies, etc). It had the effect of flattening the narrative, suggesting (to me, anyway) that Roach herself was less excited about this subject than others she has tackled. I was restive and bored through much of the book, and the one chapter I most looked forward to reading, the one about aviation and birds (a subject I know something about), downplayed the seriousness of airfield bird and animal strikes.

“… and so anything you could do that made you norMAL was desirable; and since that could easily be faked, it worked best if it were some activity that would get you killed if you did it wrong.”

— Neal Stephenson, Termination Shock

Termination Shock

Termination Shock

by Neal Stephenson

![]()

I put this one aside to read the final novel of The Expanse series, “Leviathan’s Fall.” I considered not picking it up again, but I did, forcing myself to finish it out of respect for the body of Stephenson’s science fiction work. “Termination Shock” is not as awful as KSR’s “The Ministry of the Future,” but there are off-putting similarities.

One is Stephenson’s compulsion to explain things, whether necessary or not, usually at length. It’s not enough to mention that Willem is struck by the fact that Bo, sitting in a train station cafeteria, is reading an “actual newspaper”: we have to be told that an “actual newspaper” involves ink on paper, arranged in columns, with headlines and colorful graphics. I’m surprised we didn’t get several pages on typesetting and fonts, and perhaps a brief history of Sumerian tablets. After several similar explanatory diversions, I realized Stephenson injects details in order to explain them.

And my god, “norMAL.” Somewhere in the opening pages a Dutch character speaks the word in accented English, pronouncing it norMAL. Okay, noted. Why, though, over the ensuing 700-plus pages, does Stephenson have to type norMAL every single time a European character utters the word? Europeans pronounce many English words differently, but only norMAL gets this treatment.

There’s too much talking. By the second half of the novel I was flipping past page after page of dialog — discussions between characters speaking face to face or via text message, verbatim transcripts of fictional speeches given at fictional conferences, lengthy technical explanations in the form of lectures given by main or minor characters — to get to the action paragraphs that moved the story along. It got worse toward the end, where I skimmed over what must have been fifty pages of dialog and exposition to get to what actually happened with Rufus, Laks, T.R., and Saskia at Pina2bo.

The point of all the exposition and dialog, of course, is to teach the reader about a potential means of mitigating the rise in global temperatures; the outsized role independent actors and small nation-states with more freedom to act than their larger counterparts may be able to play in taking action; and the potential social and political ramifications that might ensue. I learned about things I didn’t knew existed: the Line of Actual Control between China and India, the history (and importance of) the Netherlands and Venice, the exploitation of Papua New Guinea, the geography of areas subject to flooding as sea levels rise.

Stephenson likes to play around with popular memes, which is fun for readers up on such stuff, but I feel it will unnecessarily date the novel for those who may come to it ten years from now, or even next year — 2019’s “30-50 feral hogs” tweet, for example, inspires a memorable opening chapter — but it’s already dated and I can see future readers scratching their heads over it.

The characters Stephenson invents are colorful, well-developed, and interesting, and I came to like them. I just wish they got on with things and didn’t talk so goddamn much. That’s my main problem with “Termination Shock,” and the reason I rate it at just three stars.

“The most addictive drug known to America. Racism. It causes wealth, an inflated sense of self, and hallucinations.”

— Jason Reynolds, Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You

by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi

![]()

Did not finish; no rating.

I wanted to read and review one of the books being protested by parents and organized right-wing groups at school board meetings around the country. Many attempts to ban books from school libraries and classrooms center on works with LGBTQ themes, but many more are directed at books and novels about racism and its effects on the lives of Black Americans.

“Stamped: Racism, Antiracism, and You” by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi is a reworked version of “Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America” by Ibram X. Kendi alone. The reworked version was written for school children and is being used in classrooms around the country. It is also a target of book banners. For that reason I reserved a copy from my local library.

Alas, after three chapters I could not go on. It’s dumbed down and patronizing in such a cringe-inducing way even children, its target audience, might feel they’re being talked down to. And it’s contradictory, opening with the strong assertion that white racism toward Black people as we understand it today originated with one Portuguese slave trader in the 1400s, then just a few pages later tracing it back to Aristotle. I skipped to reader reviews posted to Goodreads, many of which pointed to other errors of fact and ahistorical interpretations, and decided to abandon the book.