It’s fun to get a question from a reader, especially a good one I can share the answer to with my Air-Minded readers. Like this one:

What’s a day in the life of a fighter pilot? Your alarm goes off and you wake up … what’s it like? How often as a career pilot do you actually get to spend flying, or is there a lot of in-between on the ground work you did? The days you aren’t flying, are you sitting in a classroom learning and reviewing, or is there other stuff you did as part of maintaining your skills?

Some basics first. Your work week as a fighter pilot varies depending on your experience level, where you are, and what your unit is tasked to do. In peacetime, flying at your assigned base or home station, it’s generally a Monday through Friday job, dawn to dusk (except during periods of night flying), and you put in 45-50 hours a week. In combat, deployed to a forward location, you’re on duty 24/7 and can expect to work 60-80 hour weeks, ditto during peacetime exercises and alert.

A fighter squadron normally has 24 aircraft and 35 assigned pilots, plus a few attached pilots who work at wing or higher level when they’re not flying with you. In my day, I could count on flying 3-4 times a week, sometimes more. During exercises, for example, I’d fly 6-8 times a week.

Here’s how a single peacetime training flight breaks down:

- If you’re leading a flight, you start preparing the afternoon or evening before

- Mission briefing begins two hours before takeoff time (three hours in combat, where there’s a mass aircrew briefing an hour before the individual flight briefing)

- You step from the squadron to the aircraft one hour before takeoff

- The flight itself lasts 1 to 1.5 hours (approximately double that if a tanker is available for aerial refueling)

- Debriefing is at least an hour long

- One flight = 4 to 6 hours, longer in combat

During exercises and in combat, you may double- or triple-turn during a flying day. There’s still a briefing before and after, but after landing from the first mission you stay in the jet, taxi to a hot pit and refuel, get a fresh load of weapons if required, then launch on another mission with minimal time on the ground. This makes for a very full day, as you can imagine.

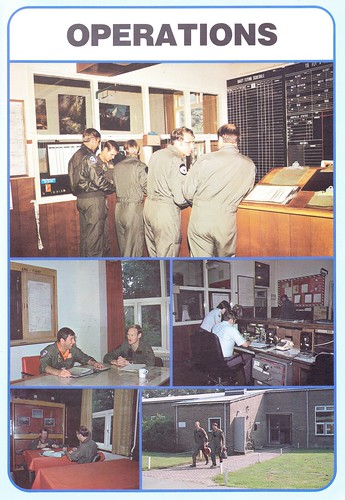

What do pilots do when they’re not briefing, flying, and debriefing? Every pilot in the squadron has a job. These jobs, sometimes called additional duties, keep the squadron running and support the mission, which is to train for combat. You start out, as a new and inexperienced pilot, as “snacko,” keeping the squadron snack bar stocked and clean. As you gain experience, you move on to more important and demanding additional duties.

You may, for example, spend your nonflying hours scheduling squadron pilots for training missions, or tracking their training to ensure they’re accomplishing the required events needed to stay current and qualified (so many night landings per quarter, so many aerial refuelings, so many instrument landing approaches, so many simulator sessions, etc). You may work in the plans shop, posting the latest changes to classified combat operation plans, passing the info on to other pilots, and keeping the go-to-war kits up to date with current maps, enemy surface-to-air missile site locations, etc). You may work as a flight safety officer or as a specialized academic instructor for aircraft and weapon systems or instrument flight training. You may be assigned as project officer for an upcoming deployment, in charge of lining up air refueling support for an over-ocean flight, plus ramp space and billeting at the deployed location.

You may be the squadron’s functional check flight pilot, flying jets that have just come out of major maintenance to ensure everything’s working right. If you’re an experienced pilot, you may spend half your day in the control tower, acting as supervisor of flying during local training missions, prepared to divert airborne pilots if the weather crumps or to assist if anyone has an emergency. You may supervise fellow pilots as a flight commander, an operations officer, or a commander.

Between flying and additional duties, you work a full day, and that doesn’t count self-study, professional military education, preparing for the next day’s missions. Everyone has a job; everyone is busy; every job supports the mission.

Since part of your question was “how often as a career pilot do you actually get to spend flying,” I’ll add this:

What I described above is the kind and amount of work you do during an active flying assignment. With few exceptions, USAF pilots will work a mix of flying and nonflying assignments over the course of a career. I spent a year doing nothing but flying during pilot training, followed by three years teaching new students to fly the T-37 as a pilot training instructor. I went on to nearly a year of F-15 pilot training followed by a three-year-plus flying assignment in the Netherlands, then another three years flying F-15s in Alaska. From there I went to staff college and a three-year nonflying assignment with US Special Forces Command, then back to F-15s for two and a half years flying in Japan. I spent the next four years as chief of flight safety for Pacific Air Forces, primarily working in an office but with frequent unit visits and flights with assigned units in Japan, Korea, and Alaska. My final assignment was a nonflying one, supporting Red Flag exercises at Nellis AFB, Nevada. My career, with its mix of mostly flying assignments interspersed with a few nonflying ones, was typical for pilots of my day (mid-1970s to late 1990s).

Times and budgets change. I can’t speak to the amount of actual flying time fighter pilots log today, although I read there’s a push on to improve simulator training to make up for shortfalls in flying hours. From all I hear the expected career mix of flying and nonflying assignments has not changed significantly.

Being at the top of your game as an air-to-air or air-to-ground fighter aircrew is exceptionally demanding. The skills are highly perishable ones, and the more training you can get, the better. My squadron mates and I knew the adversaries we’d face in combat did not get nearly the level of flying time and practice we did, and had great confidence in our ability to prevail should we ever go to war. I know the guys and girls flying today have the same level of confidence … flying hours may be more scarce than in my day, but we have better sims, and today’s USAF aircrews still enjoy a lopsided training advantage over potential adversaries.

Thanks for all your articles, found your blog during my search on internet about Airbase Soesterberg.

I read all your stories and they are very informative and especially the ones where Soesterberg is involved are really appreciated. As a teenager I was many times at the base to take pictures and the whole base and its missions were a complete mystery to us. Your blog give a nice view about what was really going on.

If you like I can send you some pictures about how the base looks these days without the jets. CNA is still in use , now by special police force so not accessible (if you try hard, you are able to see the ZULU hangar) and the rest of the airbase is turned into some sort of nature and a national military museum and some parts of the airbase left like the third generation HAS at the north shelter area and the munition area. Most structures will not receive any maintenance unfortunately and a lot are demolished, what a waste.

Best regards,

Bob