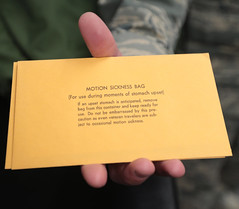

Every time I flew, one these little envelopes flew with me, stowed in an unzipped pocket where I could get to it in a hurry.

Every time I flew, one these little envelopes flew with me, stowed in an unzipped pocket where I could get to it in a hurry.

The habit dated back to my dollar ride in Air Force pilot training. “Carry a barf bag whether you think you’re prone to airsickness or not,” my instructor pilot said, “because you never know.” We all got the same talk. I’d be surprised if there’s a single military pilot, no matter how many tens of thousands of hours he or she has racked up, who’d consider flying without one.

Many student pilots barfed during training, especially on the first few flights. Some of my classmates threw up every time they flew (to this day I stand in awe of their determination). I was one of the lucky ones. I was airsick once as a child, but never during my Air Force flying career. Nevertheless, I took my instructor’s warning to heart and, like a teenaged boy with a condom stuffed in his wallet, always flew prepared … because you never know.

One morning at Vance Air Force Base, when I was about three months into the primary phase of pilot training, low clouds and fog settled over north-central Oklahoma. We went ahead and briefed our training missions with our IPs, just in case, but the ceiling and visibility was so low it seemed certain we wouldn’t turn a wheel that day. So I had a cup of coffee. Then another.

And suddenly a sucker hole opened up over the city of Enid and the word came down from operations: “Launch the fleet!”

My IP, Capt. Chris Gilchrist, and I headed to life support for our helmets and parachutes, then stepped to our T-37. We’d briefed a standard single-ship syllabus mission: a short flight to the auxiliary field for precision instrument approaches; aerobatics, unusual attitude recoveries, and spins in a nearby working area; back to the Vance AFB traffic pattern to practice touch-and-go landings.

Starting my second GCA approach to Dogface (the radio callsign for Kegelman Auxiliary Field, 20 or so miles north of Vance AFB, where we practiced instrument approaches to avoid clogging up the busy pattern at Vance AFB), I began to regret that second cup of coffee. Departing Dogface and climbing into our assigned working area, I began to suspect I wouldn’t be able to finish the flight without peeing. I managed to hold it through the aerobatics and spins, but was squirming in the ejection seat by the time we started home for touch-and-gos. My IP, sitting right next to me, couldn’t help but notice and asked what was going on. I told him I was on the verge of having a physiological incident. “I have to pee, sir, real bad.” “Well, use your barf bag,” he said.

The T-37 is a small training jet. There aren’t any facilities, not even a relief tube (I don’t even know what one of those looks like … no USAF aircraft I ever flew had one, and I think they’re some kind of WWII urban legend). The USAF has always had piddle packs (now in male and female versions), but we didn’t carry those in pilot training, where no sortie was longer than an hour and a half. My IP, I quickly realized, was right: the barf bag was the only option.

I hated having to pee in a bag in front of my IP (who politely took the stick and looked away while I took care of business), but urgency overruled embarrassment and I filled the bag, then tied it up with the paper-coated wire band that came with it. “Okay, I’m done,” I said, starting to stow the bag in my leg pocket. “Don’t put it there,” Captain Gilchrist said, “it might leak and you’ll be sorry. Just put it on the floor.” And so I did.

A few minutes later, pulling two Gs in the break for runway 17L, the bag ruptured. Well, better on the floor than in my pocket, I thought. Sometimes student pilots would throw up before they could get their bag out, and when that happened the rule was you cleaned up your own mess. Crew chiefs knew the drill and kept wet and dry disposable shop rags handy. And that’s how we handled my urine spill. After I shut down the engines, Captain Gilchrist walked back to the squadron while I stayed to mop up the cockpit floor.

By the time I got back to the squadron, of course, my shame was pubic knowledge. Classmates had already begun to embellish the story. Not only had I peed, I’d sprayed the instrument panel and shorted out the radios, necessitating a comm-out emergency approach. I’d peed so much it was dribbling out the bottom of the airplane as we taxied in, and when I opened the canopy more came sloshing out. My humiliation was complete but short-lived. By the end of the week my classmates had quit ribbing me about it; a week later they seemed to have forgotten all about it. I should have known better.

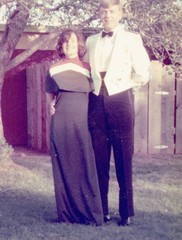

Going through old photos the other day I found a faded snapshot of Donna and me. We’re standing in the back yard of our quarters at Vance, dressed for graduation night.

Going through old photos the other day I found a faded snapshot of Donna and me. We’re standing in the back yard of our quarters at Vance, dressed for graduation night.

Pilot training lasts a year, so this photo was taken nine months after the pee incident. I’d gone on to finish another three months of training in the T-37, followed by six months flying the T-38. My classmates and I had pinned on our wings that morning. That evening we’d find out what aircraft we’d be flying for the USAF, now that we were real pilots. I’d finished in the top ten percent of my class and was hoping for a fighter. Donna and I were excited, and it shows in the photo.

After the formal speeches and dinner, but before flying assignments were handed out, the smoking lamp was lit and the informal portion of our graduation evening began … a roast, with stories of memorable highlights from our year of training. Uh-oh, I thought, here it comes. And come it did. Not only had no one forgotten the time I peed in a bag, my classmates had written a poem about it, and the commander of the flying training wing read it out loud to laughter and applause as I took my turn at the grog bowl. I can’t remember it all, but it ended like this:

They stepped out to fly,

The weather was fine,

But the bag was only rated to one point nine

In the future, Lieutenant Woodford,

Don’t be a fool,

As part of your preflight,

Tie off your tool.

Some of my classmates had to re-live even more embarrassing moments that night, and the poem was so good I actually felt honored … which, no doubt, is why I remember it 44 years later.

Equally unforgettable, I didn’t get a fighter after all. The air war in Vietnam had ended several months previously and the USAF had more fighter pilots than it needed. As a result, there were only three fighter assignments for my class. The top three graduates, as per tradition, took dibs on them.

I was number four in our class of forty. The Air Force, in its wisdom, decided to make me a T-37 instructor pilot. I stepped into Captain Gilchrist’s shoes and Donna and I spent the next three years right where we already were, Vance AFB. We didn’t even have to change quarters! It turned out that assignment was the best break I ever could have had, because after three more years flying Tweets at Vance (and telling every new student to always carry a barf bag), I stepped into the premier fighter aircraft of all time, the F-15 Eagle, which I flew for the next twenty years.

My pee-sodden past, mercifully, didn’t follow me into fighters, for which I’m eternally thankful. I can only imagine what my tactical callsign would have been if it had … and as you can imagine, I never shared the story with my Hash House Harrier mates, because the name they’d have given me would’ve been even worse!