One day in 1978, while learning to fly the F-15 at Luke AFB, I was out on a basic fighter maneuvers training sortie with an instructor in another Eagle. BFM is dogfighting: you go at each other, trying to get on the other jet’s tail in order to gun it down. We’d been fighting for what I thought had been only a few minutes when my instructor radioed “check fuel.” I glanced at the gauge and saw I was below bingo … considerably below.

One day in 1978, while learning to fly the F-15 at Luke AFB, I was out on a basic fighter maneuvers training sortie with an instructor in another Eagle. BFM is dogfighting: you go at each other, trying to get on the other jet’s tail in order to gun it down. We’d been fighting for what I thought had been only a few minutes when my instructor radioed “check fuel.” I glanced at the gauge and saw I was below bingo … considerably below.

Bingo is the amount of fuel needed to safely return to home base, and varies depending on the distance to the base and whether you need an extra pad of fuel if the weather’s iffy and you might have to divert to an alternate. Since it was a beautiful day and our working area was just 40 nautical miles from Luke, bingo that day was around 2,500 pounds* of fuel remaining. I was down to less than 2,000. Another minute or so with both engines in full afterburner and I’d have flamed out. My life flashed before my eyes. I yanked the throttles to idle and called “knock it off, two’s bingo.”

If I remember correctly, min fuel for the F-15 was 1,500 pounds, and that’s a number that doesn’t change. If you’re in the landing pattern when you hit 1,5o0 pounds, you’re supposed to declare min fuel and tower is supposed to give you priority to land. If you hit emergency fuel while still airborne, 800 pounds, you’re supposed to declare an emergency and tower has to clear you to land immediately.

I landed with a little less than emergency fuel. I shut one engine down as I exited the runway to make sure I’d make it all the way back to the chocks. The jet was so light the landing gear struts were fully extended, and when I stepped off the crew ladder I almost fell on my ass because there was an extra foot of air between the bottom of the ladder and the ramp. My heart had been in my mouth all the way back. I never declared min or emergency fuel. I never told my instructor how badly I’d misjudged my fuel state. I haven’t told anyone until now. It was a vivid learning experience, one of those things you never forget, and you can bet I never did anything like that again.

When you’re flying fighters, or any kind of aircraft, fuel is everything. You have to know not only how much fuel you have remaining at any time, you have to know how far you can go on it and how much you’ll need if things turn to shit and you have to divert. It doesn’t matter if you’re on a short training flight in the local area or part of a multi-jet package flying a long overseas deployment with air refueling tankers as escorts, fuel is never far from your mind.

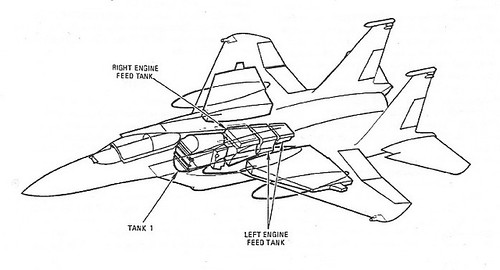

The F-15’s fuel system is pretty simple. The C model, which I mostly flew, carries about 13,500 pounds of fuel internally. There’s a tank inside each wing, and four tanks behind you in the fuselage. As you fly, fuel is transferred from tank to tank by boost pumps, first from the wing tanks to the forward fuselage tank, then from there to the rearmost feed tanks, the ones that directly supply the engines. When you get down to just the fuel remaining in the feed tanks it’s probably time to land.

Usually, though, F-15s carry additional fuel in external tanks. The jet can carry up to three external tanks, two on underwing pylons and one on a centerline pylon. Each tank holds 600 gallons, or about 3,900 pounds of fuel. In my day we generally flew with a centerline tank, bringing our total fuel load up to 17,500 pounds. Today it’s more common to carry two wing tanks, bringing total fuel up to over 21,000 pounds. When you deploy you carry all three external tanks and take off with a fuel load of over 25,000 pounds. The external tanks are pressurized, the wing tanks slightly more than the centerline, so that the wing tanks run dry first, then the centerline, and only then do you start to empty the internal tanks. Pilots call external tanks bags, and an Eagle with three external tanks is called a three-bagger. External tanks can be jettisoned for combat, of course.

|

|

|

You don’t see it that often, but the air-to-air F-15C can also carry conformal fuel tanks, those long canoe-like blisters you see on either side of the air-to-ground F-15E Strike Eagle’s fuselage, just below the wings. Each CFT carries 4,900 pounds of fuel. Strike Eagles always fly with CFTs, and occasionally external fuel tanks as well, but the Eagle usually does not. Still, it can, and F-15C squadrons sometimes load them so that maintenance can practice putting them on and taking them off, and for pilots to get the feel of flying with them (they fly great, by the way). A full load of fuel in an Eagle with CFTs and no external tanks is over 23,000 pounds.

|

|

|

Both types of F-15, the single-seat air-to-air Eagle and the two-seat air-to-ground Strike Eagle, can be loaded with CFTs and external fuel tanks. For either airplane, this results in a fuel load of over 35,000 pounds (if you’re curious, that’s 5,400 gallons), and that, combined with the 28,000 pound dry weight of the F-15C Eagle, brings its total gross weight up to 63,000 pounds (the Strike Eagle, considerably heavier to begin with, would weigh even more). That much weight, while technically within limits, puts a hell of a strain on the landing gear, so when configured with CFTs and three external tanks, standard practice is to take off with the external wing tanks empty to keep weight down, and not take on a full fuel load until airborne and hooked up to an air-refueling tanker.

Whether you’re flying a clean jet with no external tanks, or a fully loaded three-bagger with CFTs, what kind of mission you’re going to fly determines how long you can stay airborne. If you’re just ferrying your jet from point A to point B, flying at a speed that gives you max range, you can fly a hell of a long way. If you’re going out to fly BFM and you’re going to be at full grunt during each engagement (and there’s no air refueling tanker available), you might be landing 45 minutes later. Those afterburners burn fuel at an amazing rate.

I won’t pretend to know what Strike Eagle aircrews do on a typical training sortie, but the day-to-day peacetime mission of the Eagle is training for aerial combat. You fly to a working area and fight, most of the time in full afterburner. The typical F-15C combat training sortie lasts from an hour and a quarter to an hour and a half. Of course whenever air refueling tankers are available you top up between engagements, and missions are correspondingly longer. If your working area is close to the home drome and the weather is good, you can set your bingo bug (a pointer on the fuel gauge that triggers an audio warning when the needle gets down that low) at 2,000 or 3,000 pounds of fuel remaining. If, as when I was based at Elmendorf AFB in Alaska, the working areas are 100-200 nautical miles away and divert bases even farther, bingos were often up around 8,000 pounds.

Every time I flew an overseas deployment, our Eagles were configured with three external tanks. We’d join on a cell of KC-135 or KC-10 tankers at a point along the route where we still had enough fuel left to get back to where we started if the tankers weren’t there, or if there were problems with the tankers passing gas. After we took turns topping up, the tankers would then stay with us to within a few hundred nautical miles from our destination. On a typical flight from Europe to the USA, we’d each refuel five times and the flight would take about 10 hours. Without air refueling, I once flew a three-bagger from Holloman AFB in New Mexico to Langley AFB in Virginia and landed with plenty of fuel remaining. Flying with CFTs or external tanks, making it all the way from California to New York without air refueling would be a stretch, but you could easily do it with CFTs and external tanks.

Fuel is relative, depending on what you’re doing with it and how far you have to go, but it is never not important. When you’re flying, it’s not like you can take the next exit and gas up, or let the tank run dry and coast to a stop on the side of the road. Speed is life? True, if you’re flying fighters. But fuel is life, always, no matter what you fly.

*Military and large commercial aircraft measure fuel in pounds, not gallons. The reason, I’m told, is accuracy. The mass and volume of a given amount of fuel changes with pressure and temperature, but not its weight. At the altitudes and temperatures where jet aircraft operate, gallons are a less accurate measurement of fuel remaining than pounds.

Awesome stuff!!! As a non-pilot, I have read about fuel issues, but never realized it is always one of the top things you have to be mindful of. I can read the “scared” in your writing about your experience–which means at least two things: one, you are an excellent writer, which I have mentioned before, and two, it left its mark on you. Articles like this make me happy to have found this blog, and of course, by extension, you.