“My wife Norma had run off with Guy Dupree and I was waiting around for the credit card billings to come in so I could see where they had gone. I was biding my time. This was October. They had taken my car and my Texaco card and my American Express card. Dupree had also taken from the bedroom closet my good raincoat and a shotgun and perhaps some other articles. It was just like him to pick the .410—a boy’s first gun. I suppose he thought it wouldn’t kick much, that it would kill or at least rip up the flesh in a satisfying way without making a lot of noise or giving much of a jolt to his sloping monkey shoulder.” — The Dog of the South, Charles Portis

The Dog of the South

The Dog of the South

Charles Portis

![]()

I read somewhere The Dog of the South is part of a trilogy, with Masters of Atlantis and Gringos. I’m not sure Portis had a trilogy in mind, but there is a theme tying this book and Masters of Atlantis together, presumably Gringos too: a search for meaning in the paranoid and colorful Americana of small-time grifters, oddball misfits, and seekers after truth. These novels, and the characters in them, come out of the small ads you used to see in the back pages of magazines like Men’s Life and True, and still see in magazines like Popular Science. The Mysteries of the Rosicrucians! This Golf Ball Could Obsolete Many Golf Courses! Learn to Assert Yourself and Achieve Success!

I’ll be honest. I rated two other Portis novels, True Grit and Norwood, about as high as I ever rate anything: four stars each. My initial reaction to Masters of Atlantis was that while it was as interesting and amusing as the first two, it was somehow less serious, and I gave it three and a half. But I find myself still thinking about Masters of Atlantis a year later, and now that I’ve read The Dog of the South I comprehend its genius. I went back and raised my previous rating to four stars, which is where I rate this work at as well.

There are only a few authors I’ll re-read to savor their language and wit. Patrick O’Brien is one. Charles Portis is another. But before I reread Portis’ canon, I have one to go, Gringos, the as yet unread book of the trilogy. Then I’ll start in on them again, just as I keep returning to Master and Commander, the first book of O’Brien’s Aubrey/Maturin novels.

The Dog of the South is the novel of which Roy Blount, Jr. once said: “No one should die without having read it.” I’d modify the statement to read “No one should die without having read Charles Portis.” Some compare Portis to Mark Twain. Ron Rosenbaum did, in a New York Observer article titled Of Gnats and Men: A New Reading of Portis:

I’d compare Mr. Portis’ reticence in The Dog of the South to Mark Twain’s in Life on the Mississippi. I’ll never forget how stunned and pleased and impressed I was when it suddenly dawned on me what was going on beneath the surface in Twain’s account of his experience as a cub pilot learning to navigate the tricky currents, the shifting and deceptive depths of the Mississippi—how to read the river, to find intelligible clues in the patter of ripples on the surface to the dangerous labyrinth of channels below.

Brilliant, brilliant writing. I can’t wait to get to Gringos.

Telegraph Avenue

Telegraph Avenue

Michael Chabon

![]()

Oct 30, 2012: Surprised to find myself bogging down around the halfway point. To be fair, we’ve had company and I haven’t been able to read more than a page or two at a time over the past week, so maybe that’s it. Then again, I really hated the pretentious one-sentence chapter Chabon threw in, and that may have turned me against the book. Not entirely sure what’s up with my reactions here. Will plow on.

Nov 2, 2012: You can see from my earlier entry that I had a bit of trouble with this novel. I’ll expand on that in a minute. First, I should explain that over the two days following my Oct 30 comment, I fell deeply into Telegraph Avenue, and came close to giving it a four-star rating. More on that too, in a minute.

Skimming over other reader reviews, I see that some people don’t like The Yiddish Policeman’s Union (my favorite Chabon novel so far), and some don’t like The Adventures of Kavalier and Clay (my second favorite). I don’t get that, but there you go (Telegraph Avenue, by the way, is now my third favorite Chabon novel).

This is a novel about men and fatherhood, though the two main female characters are very strong and form a crucial part of the story. As a man I’m no authority, but Chabon’s women seem right to me: the way they think, the way they behave. I can’t say that about many other male novelists. But as a man I can speak with some authority on Chabon’s men. He has men, especially men of a fathering age, nailed.

Telegraph Avenue is also a novel about race, as it plays out on the streets of Oakland, California. When you see a TV commercial showing a black man and a white man palling around together (thank you Sarah Palin for that wonderful phrase) you always think, yeah, sure. But Chabon says that’s what happens in the Oakland neighborhood he writes about, and from all I know about Oakland it may be true … and in any case Chabon is convincing. Nat is white but grew up with a black stepmother in and around a largely black community. Archy is black. Together they own a used record store on Telegraph Avenue, not the Telegraph Avenue you might be picturing in Berkeley, but the section of Telegraph further south, in Oakland proper, a city with a very large black population and an important place in black American history. Nat’s wife Aviva and Archy’s wife Gwen (ditto white and black) work together as midwives. The relationships between the two men and the two women are threatened by various issues: Nat and Archy’s nearly-bankrupt business will probably go under with the opening of a big-box entertainment store scheduled to move into the neighborhood. Gwen hits a rough patch with a snotty doctor after a home birth goes bad, mouths off, and puts their hospital privileges in jeopardy.

Into this tense situation comes a 14-year-old boy, Archy’s natural son from an earlier relationship. And this boy, Titus, is temporarily living with Nat and Aviva, sleeping and having sex with Nat and Aviva’s son Julius. And then there’s Archy’s father, a former blaxploitation movie star of the 1970s, back in town and trying to blackmail a powerful Oakland councilman over a Black Panther killing decades in the past … a councilman who doesn’t hesitate to threaten Archy and Nat’s business when he decides Archy is the key to finding and silencing this troublesome voice from the past.

Oh, it’s a great plot, and once the characters clicked for me, I couldn’t put the book down. I admit, as I said in my earlier entry, that I had some difficulty getting into this novel. I didn’t initially buy the supposed normality and everyday nature of the relationship between the black and white couples. I was put off by a surprisingly lazy (and easily checked) error on Chabon’s part: Toronados never had manual transmissions, and they were never considered “muscle cars”). The pretentious and showy one-sentence chapter in the middle of the book still bugs me.

But I grew to like and care for the characters, and when the plot elements began to weave together and point toward a climax, I was fully in Chabon’s grip. I believed in Archy and Nat, Gwen and Aviva, Titus and Julie. There are no heroes in this book, no magical solutions. There are normal men and women muddling through, very true to life.

Like I said, very nearly a four-star read. Well worth your time.

A Thousand Cuts

A Thousand Cuts

Simon Lelic

![]()

Paolo Bacigalupi (The Windup Girl, Shipbreaker, The Drowned Cities) blows me away; when he said on Twitter he was reading Simon Lelic I made a beeline for the library. And by great good luck my local had a copy of A Thousand Cuts, Lelic’s debut novel.

Ostensibly this is a murder mystery about a British police inspector investigating a school shooting. The shooter, a first-year teacher, fired upon students and faculty at an assembly, killing three students, a colleague, and then himself. Much of the story unfolds through witness statements collected by the inspector, but as she gets more involved with the case some of the chapters describe her working and personal life.

Very quickly, I realized this is a story about bullying. It is endemic at the school and ignored … no, tolerated, even encouraged … by the headmaster. The new teacher, the man who snapped, had been the butt of particularly brutal bullying by faculty members and students, unable to stand up to it, unable to get anyone to help. What initially appears to be an open and shut case suddenly appears less so when it emerges that in an unrelated instance just days before the shooting, a student had been brutally attacked and part of his face cut off with a knife. The inspector tries to get at the bottom of the sickness infecting the school, but the politically-connected headmaster, backed by her police superiors, want her to wrap up the investigation by blaming everything on the dead teacher. Then, as we get into the personal and working life of the inspector, we learn that she herself is the frequent target of a male colleague’s bullying.

It is Simon Lelic’s gift to be able to show readers how intimidating and horrific sustained bullying can be, how it can rob life of all pleasure and inspire a daily sense of dread in adult and child victims alike. I count myself lucky I haven’t encountered much of this sort of thing in my life; Lelic is convincing enough that I now believe I understand why some victims of bullying commit suicide.

I’m not just impressed with Lelic’s story. I’m impressed with his writing. Those witness statements I alluded to earlier rival the best of Elmore Leonard’s dialog. Lelic has a great ear. I had the hardest time putting this book down for even the most urgent breaks; I would literally take it to the bathroom with me. I skipped meals in order to keep reading.

In short, A Thousand Cuts is gobsmackingly good. Simon Lelic joins Paolo Bacigalupi and David Mitchell on my short list of buy-everything-they-write authors.

The Troubled Man

The Troubled Man

Henning Mankell

![]()

This was my third Henning Mankell novel, and the second featuring Mankell’s most noted character, Ystad policeman Kurt Wallander. As I noted in my review of The Man Who Smiled, while the crimes Kurt Wallander gets involved in are fascinating, he does not lead the chaotic, action filled, high-threat life of the American fictional detective. In Sweden, cars do not explode, decapitations are rare, depravity is only occasionally hinted at, and guns rarely make an appearance … Wallander pursues his criminals in a well-functioning, calm country populated by stoics (if you want violent Swedish action, Stieg Larsson’s your man).

In this one, as in The Man Who Smiled, Kurt Wallander is working off the books, doing a favor for the father of the man his daughter is thinking of marrying. Soon he finds himself investigating the man’s disappearance, the apparent suicide of the man’s wife, and an unresolved spy case from the height of the Cold War. Wallander coordinates his activities with the Stockholm police inspector officially working the disappearance and suicide (another thing you’d never encounter in an American crime novel), and gradually comes to an understanding of what happened. Along the way, Wallander’s own life begins to fall apart.

Kurt Wallander has grown old in this novel and has begun to experience some issues with age … and he’s drinking to boot. He is certainly fully human, and I’m beginning to understand why so many readers are devoted to him. The novel is as much a character study as it is a mystery, and damned if I didn’t find myself caring about Kurt and his messy life.

A very good read. Unfortunately, I picked as my second Kurt Wallander novel the one where Henning Mankell retires his character, and I’m sure that’ll influence my reaction to the Kurt Wallander novels I haven’t yet read … but read them I will.

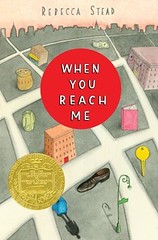

When You Reach Me

When You Reach Me

Rebecca Stead

![]()

Crap science fiction aimed at young adults is everywhere. The good stuff is hard to find. Thanks to a Goodreads friend I found this little book, devoured it in a day, and felt satisfied all over. What an absolutely great story! Minus the science fiction element, When You Reach Me could stand on its own as a YA novel about turning 12 and starting to grow up in a big city in the 1970s. With the science fiction element, it is also a charming and thoughtful tribute to Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, a great favorite of young readers (and many adults).

Good YA literature is pure … I don’t mean sexually pure, though that is characteristic of the genre … it’s pure story, without a depressing encrustation of “adult” distractions. Most of the protagonists in YA literature are old enough to have begun thinking about sex, and indeed that’s beginning to happen with the girls and boys in this story, but in the main their concerns center around friendships and trying to understand the world around them. I’m in my middle 60s and still spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about friendship and the world around me, so I don’t mind reading good YA literature, not one bit. I’ll happily put aside my alcoholic crooked cops and their cheating wives for a YA fiction break, and I emerge from those breaks feeling rejuvenated. Yes, that is the right word. Young again.

Rebecca Stead totally pulls it of with this great story. It seems almost too simple and pedestrian at first, a little like the YA classic A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, but it builds quickly and I could not bear to stop reading, even for a minute. Parts of the story reminded me of Jonathan Safran Foer’s Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, in that much of it deals with a precocious 12-year-old latchkey kid who pretty much has the run of New York City. And then the science fiction begins to make itself subtly known … I so want to talk about that part, but if I did I’d spoil the book for you.

A wonderful, wonderful book. I’m glad I read it as an adult. I wish it had been around for me to read when I was much younger.

Pop. 1280

Pop. 1280

Jim Thompson

![]()

I read an enthusiastic review of Pop. 1280 that made me think I’d missed an important chapter in American frontier lawman fiction, like somehow never getting around to reading True Grit. In fact, that’s what I was expecting (and for the first few pages hoped I’d found): the progenitor of Portis’ later novel. But instead of Portis, the author of this slim novel reminded me of Aesop, or perhaps I should say Aesop’s evil twin. Pop. 1280 is a child’s fable from Bizarro World, wherein Sheriff Nick Correy plays the role of Clever Fox, outwitting the goats of Pottsville. A sociopathic Clever Fox outwitting sociopathic goats.

There’s not a hint of conventional morality to be found in Pop. 1280. Every character is a cold-blooded killer. I was, frankly, repelled by the book’s message: nothing matters but one’s own desires, and others exist to be used.

Sheriff Nick tries to come across as a beguiling, self-effacing hick, and he sometimes throws around words that are meant to make you think he cares about people, but his actions belie his words. The story basically ends a third of the way through the novel when Nick kills his first two victims; what remains is repetition.

You may say that the morality of Thompson’s novel lies in its apprehension by the reader, who sees the evil therein and resolves to live a better life. But one might say the same thing about Bosnia: we saw the evil and resolved to live better lives, but that didn’t stop Serbs from killing Bosnians. Thompson does not take a stand; he seems to revel in Sheriff Nick’s duplicity, double-crossing, and killing.

Pop. 1280 left me empty and unhappy.