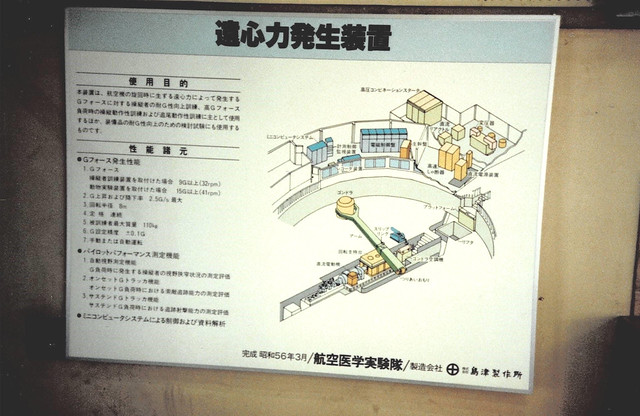

This is an encore presentation of an Air-Minded post I wrote 15 years ago. Yesterday a fellow F-15 pilot, Garry Goff, posted photos of the centrifuge I trained in, jointly operated by the U.S. Air Force and the Japan Air Self-Defense Force at Tachikawa Airfield in Tokyo. I didn’t take photos when I was there, and came up blank when I searched online for photos at the time I wrote the post. Now I finally have some, and have added them to the original post.

Here’s a way to think about pulling Gs and why it hurts: if you weigh 200 pounds, at 9 Gs you’ll weigh 1,800. Consider that for a moment. Ready for your centrifuge ride?

What happens with GLOC? Basically, the downward force on your body exceeds the ability of your heart to pump blood to the brain. As Gs increase and less blood flows to your brain, you experience tunnel vision, then loss of vision. You’re still conscious, you just can’t see. As Gs continue to increase, though, blood flow stops and you suddenly lose consciousness. As you lose consciousness your body relaxes: you involuntarily quit pulling back on the stick, the Gs go away, and you start to come to.

Your “nap” typically lasts 10 seconds or so. But you don’t come to instantly — after your 10 seconds of unconsciousness, you spend the next 10 to 12 seconds “waking up” — arms and head flailing about, unaware of who you are or what you’re doing. Aviators call the waking up phase of GLOC “doing the chicken.” Here’s the downside: if you’re in a dive when you experience GLOC, you may not fully wake up in time to avoid hitting the ground.

How many aircraft and crewmembers have we lost to GLOC? No one really knows, because we didn’t start accurately tracking GLOC incidents and accidents until the 1980s. A good guess, though, is “plenty,” and GLOC continues to be a killer.

We always knew GLOC was a serious problem, and pilots have always trained to combat it. We began using G-suits (inflatable leggings that squeeze against gut, thigh, and calf muscles) and practicing anti-G straining maneuvers (clenching leg, buttock, and stomach muscles while taking short breaths against a closed glottis) shortly after WWII. When I came into the US Air Force in the mid-1970s, this was still the state of GLOC-prevention training.

In the mid-1980s, the USAF started sending new fighter pilots to centrifuge training. Before long they decided to send experienced fighter pilots as well. It was advertised as a training program, but one with a built-in gotcha. If you experienced GLOC in the ‘fuge, you’d be grounded for a few weeks, during which you’d have to exercise daily to increase your anaerobic strength, then sent to the ‘fuge again. If you failed a second time, your fighter days were over. If you failed egregiously, your flying days might be over. What could be worse than that?

I’ll tell you what’s worse: they videotape you in the ‘fuge. If you GLOC and do a spectacular chicken, every pilot in the USAF will get to see you in a training tape. And they will laugh at you.

I got into the F-15 in 1978, back before mandatory centrifuge training. When the USAF started sending new fighter pilots to the ‘fuge, I was in Alaska serving my second F-15 tour, and had more than 1,000 hours in the aircraft. I was safe. A couple of years later, when they started rounding up experienced pilots for centrifuge training, I was serving a joint staff tour at US Special Operations Command — flying a desk, so still safe. In 1988 I got a third F-15 assignment, to Kadena Air Base in Japan. I expected to be sent to the ‘fuge during requalification training, but it didn’t happen. After flying for a year at Kadena with no apparent centrifuge threat, I figured I’d slipped between the cracks, and damned if I was going to remind anyone I’d never had the training!

I’ve pulled a lot of Gs, but have blessedly never experienced GLOC. Like all experienced pilots, when my vision started to tunnel I’d ease off on the stick and lower the Gs. As long as I controlled the G-onset rate, I could pull 9 Gs with the best of them. It’s important to note, though, that in the airplane, you never pull 7 to 9 Gs for more than a second or two. In the centrifuge, it lasts a lot longer. There, technicians control the G loading and you get whatever they lay on you. Unlike flying in an aircraft under your control, you can’t ease off on the stick to reduce Gs, nor can you control onset rate.

So there I was, starting my second year at Kadena, when my commander was summoned to a conference at Pacific Air Forces headquarters in Honolulu. In a conference room full of his peers, they put up a slide showing every centrifuge-delinquent pilot in PACAF. There were only two: Lt. Col. Paul Woodford and Lt. Col. John B______, both at Kadena. The very next day our embarrassed boss had John and I on a C-12 to Yokota Air Base in Tokyo. The day after that we were at the USAF/Japanese Air Self Defense Force centrifuge at Tachikawa.

I was in my mid-40s and John was, I’ll guess, just turning 40. By fighter pilot standards we were old men. Joining us at Tachikawa for our day of training was a 22-year-old F-16 pilot from Misawa Air Base in northern Japan. John and I decided then and there we weren’t going to take a nap no matter how tough it got or how many Gs they laid on us. Not in front of that punk-ass kid, we weren’t. No effing way.

The way it works is you spend the morning in academics, taking refresher training in effective anti-G straining maneuver techniques. Then you go into the ‘fuge, one at a time, while the pilots waiting their turn watch you on closed circuit TV as you spin through the profile.

The profile? After you strap into the seat in the centrifuge, they spin you up to 4 Gs, hold you there for 30 seconds, then spin you back down for a short break. This is to make sure your G-suit is working properly, as well as everything in the centrifuge itself. Now you go into the full profile. They spin you back up to 4 Gs for 15 seconds, then 5 Gs for 30 seconds, 6 Gs for 30 seconds, 7 Gs for 15 seconds, 8 Gs for 10 seconds, and 9 Gs for 10 seconds, during which time you have to track a simulated MiG on a head-up display by controlling a stick with your hand. Not only do you pull a lot of Gs, you pull a lot of Gs for a long time (you try weighing 1,800 pounds for 10 seconds!). There’s no break between 5 Gs, 6 Gs, 7 Gs, etc — you go straight from one G loading to the next, all the way up to 9 Gs, and the onset rate for every increase is almost instantaneous. You’d never do anything like this in an actual airplane — if you did, you’d GLOC yourself to death! But in the ‘fuge, you have to do it, and you don’t dare lose consciousness.

John went first and did fine. I went second. Damn, it was punishing — probably the hardest physical straining I’ve done in my life — but I didn’t pass out either, and in fact I tracked my MiG better than John did. The kid went last, and GLOC’ed between 7 and 8 Gs. John and I watched him come to and do the chicken. We laughed and laughed.

We had the night off in Tokyo, so John and I went out on the town, exhausted though we were. We took a taxi to a hole in the wall place in the Ginza, where two beers and two plates of gyoza, plus the taxi ride, cost a month’s worth of flight pay. As I reached out for my beer I noticed the underside of my arm was covered in little red spots. John held up his arm and he had ’em too. Later that night, back in my room at Yokota, I undressed and discovered the same spots all over my butt and down the backs of my legs. The technical name is petechia, but pilots call ’em G-measles — they’re what happen when you pull so many Gs you rupture your capillaries.

Am I glad I took my turn in the centrifuge after all? Yes, I guess I am. Would I ever want to do it again? Hell, no!

p.s. About the F-16 kid from Misawa: John and I didn’t think about it as it was happening, but over beer and gyoza that night realized we’d just watched a young man wash out of his dream assignment in fighters. The kid would have had to pass centrifuge training before he ever got to fly a Viper, so for him to be at the ‘fuge with us meant he must have GLOC’ed on a training flight at Misawa and been sent to Tachikawa for evaluation and retraining. For him, it was a do or die scenario. May god forgive us for laughing at him earlier in the day — although looking at the bigger picture, his bad day at the ‘fuge probably saved his life.

That was very interesting reading. Thanks.

Sometimes the best thing we can do for people is wash them out of our programs. For their own safety and well being as well as that of others. I was a Navy Nuke, noting physically challenging about that but the academics (which continue for your ENTIRE career) can be a bit unnerving at times. And the expectations for casualty response are high and unforgiving. Those who struggle “at the cut line” often wind up very demoralized down the line. I’ve had a few kids who, years after washing out, reached out and thanked me for “helping” them find a career path more to their suiting.

I’m presuming the kid who GLOC’d out was afforded the opportunity to continue serving, just in a different capacity, and I hope he found something rewarding (even if it’s not as cool as flying a Fighting Falcon)

Gopher, I don’t know what became of the Misawa kid, but a few months later we had a new lieutenant GLOC in an F-15 at Kadena. His flight lead saw him roll out of a hard high-G turn and start descending toward the water and realized he’d GLOCed. He started calling “pull out” on the radio and the kid responded in time to recover. But same thing … the new guy had done the centrifuge before ever getting checked out in the Eagle, which shows you the training is no guarantee against GLOC. We sent him to Tachikawa and he GLOCed again in the ‘fuge. He got two weeks off to work out in the gym, then another shot at the ‘fuge, where he GLOCed again. He went up before a flying evaluation board, which recommended he keep his wings but be reassigned to crewed cargo or tanker aircraft. He took the deal and that’s the last we saw of him. That’s probably what happened with the Misawa kid.

Q for you. Did you have to be interviewed by Rickover? I had a sub guy in my AFSC class who did, said it was as intimidating an experience as everyone said it was.