“The sun peers over the rim of the earth, casting its blaze across Bangkok. It rushes molten over the wrecked tower bones of the old Expansion and the gold-sheathed chedi of the city’s temples, engulfing them in light and heat. It ignites the sharp high roofs of the Grand Palace where the Child Queen lives cloistered with her attendants, and flames from the filigreed ornamentation of the City Pillar Shrine where monks chant 24-7 on behalf of the city’s seawalls and dikes. The blood warm ocean flickers with blue mirror waves as the sun moves on, burning.” — Paolo Bacigalupi, The Windup Girl

Caly’s Island

Dick Herman

This novel is a departure for Dick Herman, who has written several military-themed novels grounded in reality and current events … not, though, a total departure: Dick’s normal characters are mature professional men and women, and that is the case here, with the story revolving around a group of mostly retired small boat sailors from various backgrounds.

The departure is in what happens during the groups’ sailing trip, when they are transported in space and time from the present-day Straits of San Juan de Fuca in Washington State to Greek waters in the days of Odysseus. Their ensuing adventures, which include fascinating encounters with figures from Greek mythology and even a god or two, are … I have to admit … damn fun. How interesting to see a writer like Dick Herman try on fantasy, and do a good job of it into the bargain. I would like to read more.

Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro

![]()

This is, technically, a science fiction story, but not in the sense that it is any sort of future adventure. Rather, the backdrop to the story is a present-day England in some quite nearby alternate universe where certain advances in medical science have been achieved.

The story focuses on three characters who were raised together in a sort of boarding school, following them through their brief lives. I recently saw and reviewed the movie; though it was sad, I loved it and want to watch it again. The book is even sadder. The narrator, Kathy, is a level-headed young woman who, though she pretty much knows her destiny all along, gradually comes to understand it fully, finally facing the shocking and utter bleakness of it. I’m sorry, I really don’t want to give the story line away, but Ishiguro’s central conceit is shocking, bleak, thought-provoking, and (have I mentioned this already?) really, really sad.

My one reservation? The novel is drawn out and repetitive, unlike the movie, which tells the story far more efficiently while losing none of the emotional impact. My advice to you? See the movie first. If you’re still intrigued, read the book.

Perdido Street Station

China Miéville

![]()

Perdido Street Station is a blend of science fiction and fantasy, with elements of steampunk and magic. Mieville, in an interview, described it as “basically a secondary world fantasy with Victorian era technology. So rather than being a feudal world, it’s an early industrial capitalist world of a fairly grubby, police statey kind!” This novel, I thought, was richer and more fully developed than Mieville’s The City and the City (reviewed here).

China Mieville is fascinated with the cartography of alien worlds, in this case the world called Bas-Lag, full of imagined cities in imagined countries on imagined continents. New Crobuson, the city whose hub is Perdido Street Station, is a cosmopolitan hive inhabited by humans and various forms of xenians, from the spiny cactactae people to the amphibious vodyanoi, living together in guarded harmony, here threatened by an invasion of nearly-unstoppable slake moths, fearsome predators with no natural enemies who fly by night and suck memories and personalities from their victims. The protagonists are a small band of not-at-all-heroic humans and xenians, brought together by accident, pursued by New Crobuson’s criminals and police. All this against the backdrop of a lovingly detailed city with an absurd number of named, unique neighborhoods, stabbed here and there with the towering spikes of the militia, overlaid with elevated railroad bridges and trestles, monitored by the militia’s airships.

Slake moths are not the only things to fear in New Crobuson, of course. The militia is everywhere, as are the criminals, augmented by “remade” humans and xenians. Our antiheroes must also deal with a heretofore-unknown and unsuspected machine intelligence, all the while watching out for tricks of thamaturgy. And then there are the ambassadors of Hell and the multi-dimensional Weavers.

It’s a grand adventure and it fully held my interest for the first 400 or so pages. The last 200 pages dragged a bit, with Mieville setting up cliffhanger after cliffhanger as the climactic confrontation with the slake moths approached … during those final chapters, I kept wishing Mieville would just get the hell to it.

But I have to say the novel was a very satisfactory read, and I expect I’ll read more. Perdido Street Station is just one of three Mieville novels set in the world of Bas-Lag, so I still have The Scar and Iron Council to look forward to.

The Windup Girl

Paolo Bacigalupi

![]()

Even though I sometimes use it myself, I’m getting tired of the “punk” label: steampunk, cyberpunk, biopunk. Let’s go back to the big tent theory and call science fiction what it is: science fiction. You will hear people try to fit The Windup Girl into any one of these punkish niches, and I suppose you could do that. Biopunk: yes, much of the story has to do with genetic engineering. Steampunk: sure, there are dirigibles aplenty, and mechanical contrivances running on clockwork and alternative fuels. Cyberpunk: why not? The spirit of William Gibson is strong in this book. I’m going to call it science fiction … outstanding science fiction … and let the matter rest there.

Just by way of establishing credentials, The Windup Girl won the Nebula Award in 2009. In 2010 it won the Hugo award. Time Magazine listed it as one of the ten best books of 2009 … that would be one of the top ten of all books, in all genres, published in 2009.

Paolo Bacigalupi’s vision here is so rich, so detailed, it’s hard to know where to start. He writes of a collapsed world: post-oil, post-American, post-global trade. Genetically engineered crops have gone horribly wrong and fierce new diseases have destroyed agriculture, killed millions, and laid waste to whole countries. Much of the once-developed world is now wasteland. Thailand is hanging on, trying to keep existing crop diseases from spreading and new diseases from penetrating its borders, trying to feed its people and to keep foreign influences out, fighting a vicious war with Vietnam. Japan is a small regional power, likewise India; China is no more. AgriGen, a global non-state corporate power, schemes to invade Thailand to steal its closely guarded bank of preserved pre-collapse seeds.

Bacigalupi takes us into this world through a cast of wholly believable characters: a farang (foreign) businessman and undercover agent for AgriGen; a despised yellow card Chinese, once a powerful clipper ship fleet owner but now a refugee on the run; two officers of the feared Environmental Ministry who find themselves front and center in the political and military struggle for control over Thailand; and Emiko, a manufactured woman, genetically engineered and mechanically augmented, in the country illegally and hiding from the authorities, slowly discovering her remarkable built-in capabilities … the wind-up girl of the title.

I read Paolo Bacigalupi’s second novel a few months ago and reviewed it here. Ship Breaker, a young adult novel, was a revelation to me: good science fiction with great characters, super-realistic settings, solid science, rich detail. The Windup Girl, an adult science fiction novel, is even more so. I must say, Bacigalupi’s science fiction is the best I’ve read in years.

When I read Bacigalupi, I hear echoes of David Mitchell, Margaret Atwood, and in the case of The Windup Girl, Cordwainer Smith, who wrote the SF classic The Ballad of Lost C’Mell. God, this is good stuff. I want more!

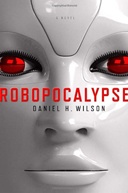

Robopocalypse

Daniel H. Wilson

![]()

“Peeking out from my covers, I see there’s a rainbow of flashing lights coming from our wooden toy box. The pulsing blues and reds and greens flicker from the crack under the closed lid and spill out onto the alphabet rug in the middle of the room like confetti.”

That, dear reader, is a 14-year-old girl talking to a fellow survivor in the smoking rubble of a destroyed skyscraper as killer robots roam the streets. Does that sound like any 14-year-old girl you’ve ever known? Me either.

All the narrators of this book, who speak to us in the form of recorded conversations, debriefing transcripts, and electronic data bursts, sound like that 14-year-old girl. Which is to say that the characters who tell the story all sound the same … and equally unbelievable. I’d much rather the author had abandoned the pretense of recorded conversations and transcripts and just told the damn story.

Dan Wilson, who has an academic background in robotics, doesn’t really give us much in the way of robotic information. How did Archos become self-aware? How did he manage to put himself together, to assemble the parts and pieces he needed to communicate with and direct the activities of other robots? Where are the factories he set up to manufacture his robot army, and where does he get the electronics and other raw materials he needs? How are the robots powered? How is it that Archos, seemingly aware of every single thing every human on earth does or thinks, is unable to defend himself in the end? Wilson doesn’t bother to tell us.

Vaunted background in robotics aside, Dan Wilson doesn’t appear to have any kind of background in robotic science fiction. Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics? Strangely absent from a science fiction novel about robots. I mean, my god, there’s such a rich body of robot science fiction, you’d think Wilson would have boned up beforehand. Who’s going to pick up a book with a title like Robopocalypse? Science fiction readers, that’s who … and they’re going to be disappointed.

Wilson’s writing is literate but somehow inept. His characters constantly speak of imminent, catastrophic danger … “I sensed, with icy certainty, instant death hurtling toward me from the sky” … followed by a rifle shot that misses, or a thrown rock, or some such not-even-close-to-catastrophic event. But that’s merely a minor irritation. More seriously, Wilson fails to communicate the feel of global war, of huge forces advancing and retreating across the continents, of the near extinction of the human race. His cast of characters is too small, too localized. The reader never gets the sense of end-times doom Wilson wants to convey.

Robopocalypse is thin gruel. There’s no meat in it. I felt like I was reading the screenplay of a cheap Syfy Channel mini-movie. The robots may as well be zombies or vampires, for all the scientific lack of rigor Wilson gives us. Robopocalypse is not science fiction. It’s an airport thriller, and not a particularly good one.

Metaplanetary

Tony Daniel

![]()

Metaplanetary is good old-fashioned space opera, scaled to the entire solar system and a bit beyond, taking place approximately 1,000 years from now. The inner system, led by evil dictator Ames, is at war with the freedom-loving rebels and cloudships of the outer system. Exciting stuff! Unfortunately it turns out to be the first of a two-book deal, and a lot of interesting characters are left hanging from cliffs at the end. Will I buy the second book to find out what happens? I don’t know. Why don’t I know, you ask?

Skimming other readers’ reviews of Metaplanetary, I encounter one comment over and over again, a variation on the theme that the science behind Tony Daniel’s future solar system is “solid.” I’m not at all certain that is the case. Daniel writes of a solar system where the inner planets and moons, from Mercury out to Mars and some way into the Asteroid Belt, are connected by organic snot-filled tubes made of nanotech material called “grist.” Thoughts and intelligence travel instantaneously from one end of the solar system to the other, thanks to the pioneering work of 25th century scientist Merced, after whom the interplanetary communications network called the Merci is named.

Artificial intelligences called “converts” (there are enslaved converts and free converts, and strong societal prejudices against the free ones) can couple with humans (ditto strong societal prejudices) and produce human-plus offspring. What distinguishes free converts from Large Array Personalities? Ah, the LAPs, you see, are fully human, with no AI involved (or maybe some, but I am confused on that point). In any case, you wouldn’t mind a LAP moving in next door or taking your daughter out on a date.

But that’s not all. Humans can transform themselves into AIs or free converts, and then, whenever they want to enjoy a cigar or the feel of grass beneath their feet, whip up a physical body out of free-floating grist. These temporary physical manifestations are called pellicles, as best I can make out. Some free converts operate several physical bodies at once, which act independently while staying part of the unifying mind. Want immortality? Convert yourself into an AI, then back into a younger body made of grist, reapply as necessary! While all this wonderful stuff is going on, simple humans as we know them today populate the moons and planets, content to live nasty, brutish, short lives. With all these other possibilities, why would anyone settle for that? We never find out, because regular humans are not really part of Tony Daniel’s story.

Some free converts have migrated beyond the solar system and now live in the Oort Belt … or perhaps it is the Carbuncle … as giant cloudlike space ships. Of course they also slap together grist pellicle bodies from time to time in order to participate in and interfere with regular human affairs. Scraps of computer code, floating around since the end of the 20th century, have been made into rats and ferrets (they keep the snot tubes clean). Regular humans who live on Mercury are Mercury-adapted, yet can climb into the nearest tube and pop out on Mars, seemingly with no physical adjustment for gravity, atmosphere, or temperature. Or what the fuck, I guess if there’s a problem they just turn themselves into spaceships and fly off to Alpha Centauri.

You see the problem I’m having with Tony Daniel’s “solid science”? Right. Maybe it is solid, but as Arthur C. Clark famously said: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Tony Daniel might as well be writing about Hogwarts and Harry Potter. Having a bit of a problem breathing methane at 4.5 times the pull of earth gravity? Just wave your magic pellicle grist wand and say “adaptaramus!”

So, will I read Superluminary, the second book of the series? Probably. But I’m going to spend some time in the 21st century first. I’ll get back to Tony Daniel’s space opera in a few months.

“Speculative fiction” is the new name for the formerly pure sci-fi genre, for those few of us who care about genres. As for me, I’m still read on a Wodehouse marathon. Such blithely hilarious stuff.

Actually, Reliza, I think the term “speculative fiction” was adopted by publishers to gussy up the image of their science fiction and fantasy catalogs. Amazon still categorizes the genre as “science fiction & fantasy”; B&N uses “science fiction, fantasy & horror.” Personally I prefer to maintain the distinction, an important one, between sci-fi and fantasy.