“Out of the blue and into the black is what they called going into a tunnel. Each one was a black echo. Nothing but death in there. But, still, they went.”

—Michael Connelly, The Black Echo

The Black Echo (Harry Bosch #1)

The Black Echo (Harry Bosch #1)

by Michael Connelly

![]()

In an earlier review, I commented on the differences between Elmore Leonard’s literary character Rayland Givens and the Rayland Givens of “Justified,” the FX television series. Now I feel obliged to comment on the literary and TV versions of Harry Bosch (the TV series, titled “Bosch,” is on Amazon Prime).

I knew the TV Bosch before I met the literary one, but had no trouble adjusting between the two, since TV Bosch is so faithful to literary Bosch. When I read the book, I pictured the actor who plays Bosch on TV. The personalities match. The stories, if I’m not assuming too much from the first novel in the series, generally match. Offhand, I can’t think of another TV series that is so similar to the books that inspired it … “Game of Thrones,” maybe?

“The Black Echo,” the first of 20-some Harry Bosch novels, is a good intro, especially for readers who knew Bosch on TV before they came to the books. It fills in Bosch’s background and explains why he’s considered an outsider in the LAPD. It’s not always necessary, but in general I recommend starting any series of books with the first one.

These are police procedurals, and though the crimes are complex, Connelly doesn’t make their resolution tricky … Bosch unfolds cases methodically, using old-fashioned shoe leather and diligent detective work, and if there are twists, the reader can see them coming a block or two away. I don’t mean to suggest the crime Bosch solves in this novel isn’t exciting … it’s a good read.

In this first novel, Bosch comes across as a bit of a cold fish, a little less sympathetic than his TV counterpart, but I’m assuming his character grows in later novels. Yes, I will continue to read these novels. They’re straightforward and good; LA noir without LA noir’s excesses (like drug addicted or alcoholic protagonists, always a turnoff with me).

Never Go Back (Jack Reacher #18)

Never Go Back (Jack Reacher #18)

by Lee Child

![]()

In this, the 18th Jack Reacher novel, we return to the present day. Reacher finally hitchhikes to the DC suburbs of northern Virginia to meet Major Susan Turner, current commander of the elite MP unit he once led, a journey he started four novels earlier. But he has to wait a little longer, because he’s walked into a minefield sowed by a crooked military cabal, with Turner jailed and inaccessible, and Reacher himself threatened over past transgressions he doesn’t remember. Weirdly, rather than throw him in the brig, the Army puts Reacher back on active duty.

Okay, enough spoilers. You know what happens next, or you should if you’ve read the previous 17 Jack Reacher novels in order. Which I have. I will merely say Reacher doesn’t disappoint. Nor does Susan Turner, once we finally meet her.

Somewhat disappointingly, there’s only one personality to go around between three main characters: Reacher, Turner, and a fourteen-year-old girl named Sam. They are all so much alike one might almost think Lee Child was being a little lazy. They are all Reacher, right down to habitual phrases they utter under stress. That is one small negative mark against this installment.

Speaking of habitual phrases … in an earlier Reacher novel, as the deadline to defuse a terrorist threat neared, Lee Child ended each chapter with a countdown: “twenty-one hours to go,” etc; in another each chapter ended with a variation on “Jack Reacher. Cocked and ready to fire.” In this one, chapters end with Reacher telling himself or others that the odds on the next coin toss are fifty-fifty … but somehow it never is fifty-fifty, because Reacher always guesses right. But you knew that was going to happen.

This novel ends with a standalone short story about the 16-year old Jack Reacher, passing through New York City on his way to visit his older brother Joe, a cadet at West Point. Guess what? Reacher was his fully-formed adult self as a teenager. Once again, one might think Lee Child is being a little lazy.

But all in all, fun times.

Personal (Jack Reacher #19)

Personal (Jack Reacher #19)

by Lee Child

![]()

I have to hand it to Lee Child for having the courage and integrity to be different. John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee, if I recall correctly, gets laid in every novel. As does every other thriller hero I can think of. Jack Reacher doesn’t, which means he’s not a total stereotype, which means his creator isn’t a total tool.

By now you will have guessed Jack Reacher remains celibate throughout “Personal,” in spite of working with two very eligible women, one of whom at least is his equal in bravery and tradecraft (Travis McGee’s women ran toward the damsel in distress end of the scale, decidedly the weaker sex).

This is another in the Jack Reacher series where he crosses paths with Army brass he used to work for, who send him and a young CIA sidekick to Paris and London, where the story of this novel unfolds. As is the case with most Jack Reacher novels, the story unfolds in a familiar, well-worn manner: Jack stays one step ahead of developing events and is the first to sense that things are not what they appear to be; Jack kicks some righteous ass; Jack zeroes in on the mastermind behind a complex conspiracy; Jack finishes up in a closed room with the mastermind, explaining details the reader may not have fully grasped.

By now, I welcome a new Jack Reacher novel as I would an old friend. Unless it is the odd clunker, the novel comforts me, and I will be sad to reach the end, because as good as most of them are, they’re not good enough to read again.

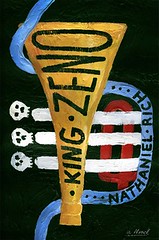

King Zeno

King Zeno

by Nathaniel Rich

![]()

I was struck by how strongly this novel resembles the period novels of Dennis LeHane: “The Given Day,” “Live By Night,” to mention just two. Both authors place their characters in American cities in the early 20th Century, acting out stories in front of a backdrop of historical events. In “King Zeno” the backdrop is New Orleans in 1918, and includes the crossover of jazz music from black society to white society, the devastating Spanish flu epidemic, the mystery of a serial killer (the Axman, who in real life was never caught), and the construction of the very canal that decades later failed and flooded great parts of the city.

The cast of characters includes New Orleans policemen, an up-and-coming jazzman named King Zeno, and the mother and son of a Mafia family trying to become respectable by building the canal. The characters are a blend of fiction and fact: there was no King Zeno, but there was a young Louis Armstrong. The Axman mystery was never solved, but here the axman is identified and killed.

The novel’s a bit of a slow read at the beginning but picks up by the second or third chapter. Some readers may be put off by Rich’s attempt to put period slang in the mouths of his characters (I’m certain the slang is accurate and well-researched, but it’s jarring to hear jazz called jass, as it apparently was in 1918). Others may be put off by a white author trying to write convincing black characters, but I have no issue with that and I think Rich pulls it off reasonably well. His description of the desperate lives of King Zeno and his friends is certainly grim enough, and probably right on the money … they could work only the most menial of jobs, and for almost nothing (jazz, for a lucky few, was about the only avenue of escape).

It’s a good story, somewhat marred by contrivance and melodrama, particularly in the way Nathaniel Rich uses his fictional characters to connect unrelated historical events, giving those characters important roles to play in those events; but even more so by the heavy-handed ending, where all the characters converge in a gruesome climax.

Still Waters (Sandhamn #1)

Still Waters (Sandhamn #1)

by Viveca Sten

![]()

A murder mystery set on a small Swedish island not far from Stockholm, nicely translated into English. It has a sort of English summer garden mystery feel (or more precisely a “Midsomer Murders” feel), in that the good guys—Thomas the policeman, the young cops assigned to help him with the murders, and Nora, a childhood friend who helps Thomas solve the case in an amateur way—are Nice with a capital N. The location, a small island Swedes love to visit during the summer, is nice too.

The mystery is nice in that the whodunit is not immediately obvious to the reader; Viveca Sten drops just enough clues so that we’re carried along with Thomas, his fellow cops, and Nora, not getting to the reveal until they do.

The bad guys, of course, are not so nice, and as clues drop an evil conspiracy begins to take shape, but in the end I was surprised. The surprise was not contrived at all, as it is in many mysteries, but organic to the story in a way that holds together, a very human way. And that’s nice too.

Although in the end the crime is solved, Viveca Sten leaves a few things up in the air. What will become of Thomas and Carina? What will Nora do about her asshole of a husband? Is Nora the one Thomas should be with and not Carina? Grist for Sandhamn #2 and beyond.

Overall, though, maybe a little too nice. The book more than held my interest, but I missed the grittiness and depth of other Scandinavian mysteries. Once you’ve read Stieg Larsson, niceness in a Swedish mystery is not what you expect.

The Thousandth Floor (The Thousandth Floor #1)

The Thousandth Floor (The Thousandth Floor #1)

by Katharine McGee

![]()

In a recent blog post, Mimi Smartypants recommended some books. Among them was a young adult science fiction title: “The Thousandth Floor.”

Mimi’s been blogging since 1999 (!) and is one of the best & brightest voices on the net, so when she recommends books I pay attention. This one sounded right up my alley. I’ve read some excellent YA sci-fi, and the hook of “The Thousandth Floor,” a literal 1,000-floor residential skyscraper in a future New York City, reminded me of the water-conserving vertical arcologies the wealthy and powerful inhabit in Paolo Bacigalupi’s “The Water Knife,” and the community towers built below and above a flooded Manhattan in Kim Stanley Robinson’s “New York 2140.”

The sci-fi hook of “The Thousandth Floor,” however, turns out to be mere backdrop for a teenage romance novel. There’s virtually no exploration of how such a densely-packed tower society might function, what impact gargantuan vertical arcologies would have on surrounding cities and society at large, no speculation on the kind of economy that would make such communities self-sustaining.

Instead we get a pack of idle rich teenaged parasites being petulant and selfish, mooning over who’s sleeping with whom, popping drugs and guzzling alcohol, scheming to do their enemies in. Cecily von Ziegesar’s “Gossip Girl” kept coming to mind, and I noticed other reviewers had the same reaction.

One positive note, though: Katherine McGee doesn’t make a big deal of her characters’ sexuality (which in at least one case many readers will find shocking); she presents them doing what they do, refreshingly free of negative or cautionary commentary.

For now I’m going to assume Mimi Smartypants had not started reading “The Thousandth Floor” before recommending it. Because I believe we think alike, and I most certainly would not have.

Red Sparrow (Red Sparrow Trilogy #1)

Red Sparrow (Red Sparrow Trilogy #1)

by Jason Matthews

![]()

No rating; did not finish.

The opening chapter, describing a CIA agent evading capture on the pre-dawn streets of Moscow, wasn’t half bad. The second chapter, introducing the evil Russian spymaster and his henchman, was so-so.

Then came the third chapter and the introduction of Dominika, the Red Sparrow. I at first hoped Matthews was lampooning the widespread inability of male writers to create convincing female characters, but no, he was demonstrating that very thing.

Another reviewer summed it up: “… virtually every paragraph about the heroine mentions how sexy she is. Then she goes to sex school to really sex up her sexiness.” It got worse with his description of Dimitri, the Russian oligarch in the sexy sparrow’s sights, with lavish details about his brand-name apparel, cigarette lighters, wristwatch—even his French cologne—and his state of horny. As in “Dimitri Ustinov sat across from her, humming with horny.” What really stopped me, though, was Dominika’s “synesthesia,” her ability to read people through astrally-projected colors, which reminded me of a hippie-era movie I once saw where special effects hacks had added fuzzy colored halos around characters to represent their “auras.”

I kind of liked the oddball touch of ending chapters with recipes for meals described therein, as irrelevant to the story as they may have been, but everything else was so awful and shallow and predictable and stereotyped I couldn’t go on.