You Can’t Read That! is a periodic post featuring banned book reviews and news roundups.

YCRT! News

Right-wing conservatives get upset about book banning too. But are schools in Portland, Oregon, actually banning textbooks that deny or call into question climate change? Not really.

Texas schools were encouraged to teach Mexican-American history. They’re off to a great start with the adoption of this racist textbook, which accuses Chicanos of having “adopted a revolutionary narrative that opposed Western civilization and wanted to destroy this society.” Huh. I’ve heard that kind of talk before, right here in Arizona.

After a parental challenge and administrative review, The Perks of Being a Wallflower has been banned by the Pasco School District in Florida.

Creationist homeschooling mom Megan Fox wrote a book accusing an Orland Park, Illinois public library of protecting pedophile patrons who use library computers to watch porn in full view of children. Her attack is so similar to the long-running campaign waged against public libraries and the American Library Association by an organization calling itself SafeLibraries, the editors of the political blog Wonkette might be excused for wondering if Megan Fox and SafeLibraries are one and the same.

Good to know there’s an ongoing Twitter exchange between authors about taboo subjects in young adult literature. The hashtag is #Gdnteentaboo. The Guardian helpfully provides a summary of recent issues being discussed.

Also from The Guardian, a good explainer on the Facebook trending topics controversy. As I suspected from the beginning, it’s all bullshit.

YCRT! Banned Book Review

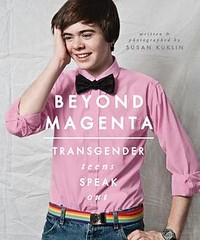

Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out

Beyond Magenta: Transgender Teens Speak Out

Susan Kuklin

I reserved a library copy of Beyond Magenta after seeing it on the American Library Association’s annual top ten list of frequently challenged books. According to the ALA, Beyond Magenta has become a target of book-banners, who say it’s anti-family, filled with offensive language and references to homosexuality, sneaky attempts to teach kids about sex, politics, and religion, and wrong for the age group at which it’s aimed. Moreover, the ALA cites evidence that Beyond Magenta is prompting some librarians and school administrators to consider pre-emptive censorship (“wants to remove from collection to ward off complaints”).

In a separate essay, the ALA discusses challenges to books about diversity, noting that while only a tiny fraction of books written for American children and students are about people of color, LGBT people, and/or disabled people, such books almost always become the targets of angry parents who want them removed from classrooms and libraries. When books about diversity are challenged, diversity itself is almost never stated as a reason; instead, parents complain of sex … and yet hundreds of other books written for children and students contain sex and are never challenged.

While “diversity” is seldom given as a reason for a challenge, it may in fact be an underlying and unspoken factor: the work is about people and issues others would prefer not to consider. Often, content addresses concerns of groups who have suffered historic and ongoing discrimination.

To be sure, to be transgender (or gender fluid) is to diverge significantly from societal norms, and Beyond Magenta is most likely being attacked for exploring a kind of diversity many people find confrontational and uncomfortable.

By encouraging six young transgender people to share their experiences with readers, I believe Susan Kuklin’s intent is to inform and educate, and also to give other young transgender people the knowledge that they are not alone. In this she succeeds. If there is any sex in Beyond Magenta, it is only at the most abstract level: two or three of the transgendered kids she interviews mention sexual preferences, but none go into detail. Sex is not what these kids are about. Gender is, and the book makes the difference clear.

Offensive language? Nope. References to homosexuality? If a biological boy identifies as a girl, and (both before and after transitioning) is sexually attracted to boys, is that homosexual? Not in the same sense in which most of us think of homosexuality, surely. Sneaky sex education? Sex is mentioned, as noted, and I guess that’s enough to send some folks into a tailspin. Political and religious indoctrination? None that I noticed. Wrong for the age group it’s aimed at? The book is clearly meant to be read by transgender teens at a serious turning point in their lives, and how is that wrong?

I suppose I should mention that of the six young people interviewed for this book, none have had sexual reassignment surgery. Each of them, however, takes hormone treatments to develop the secondary sexual characteristics of the gender they identify as.

As I mentioned, I think one of Susan Kuklin’s reasons for writing this book is to offer hope and encouragement to other transgender youth. Which is good, but … she doesn’t address the negative experiences so many transgender youth have to deal with: while a few of the young people featured in Beyond Magenta talked about teasing and resistance from parents, siblings, fellow students, and teachers, each of them managed to transition and move on; some even praised parents, peers, and schools for being supportive.

What, I wondered, about transgender kids who don’t live in socially progressive environments, who encounter non-stop suspicion, bullying, and hatred? None were interviewed in this book, and I thought Susan Kuklin’s focus too limited. Her six interview subjects seem relatively privileged, judging by horror stories I’ve heard. And what of older transgender people? The oldest interviewee was maybe 18; all six were either starting, in the middle of, or just completing the process of transitioning. What happens when transgender teens reach adulthood and middle age? What are their lives like? What are their concerns? What are the downsides of transitioning? Equally, what are the upsides? These questions weren’t addressed at all.

Finally, I have to note some LGBT reviewers have panned Beyond Magenta. Several complained that the author is not a member of the LGBT community herself: “Yet another book about trans people but not for us.” Some complained about the language and labels she uses to express sexual and gender diversity: “… much of the language used around transness was really out of date.” A few reviewers called the book sensationalistic and voyeuristic, and said it reinforces stereotypes.

None of these objections occurred to me. I’m not a member of the LGBT community either, so maybe that is to be expected. My sole objection is to the book’s limited scope. I want to know more.