I added an update to this post from 2015. If you remember reading it and just want to check the update, scroll to the end of the post. If the post is new to you, I invite you to read the whole thing.

— Paul, June 12, 2022

I loved flying fighters and trainers in the US Air Force. Unlike many of my peers, though, I didn’t want to fly for the airlines afterward. I chose another post-USAF career path, training military pilots as a civilian contract ground instructor. Today, with the hassles of airport security and the budget tour bus nature of air travel, I won’t get on a passenger plane unless it’s a matter of life or death, and even then I’d have to think about it.

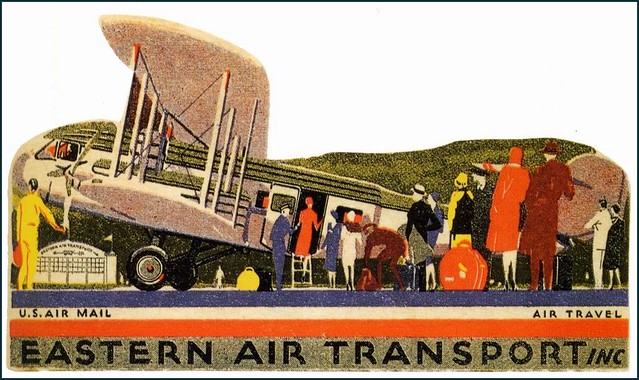

That doesn’t mean I’m not interested in air travel. I’m a volunteer docent at the Pima Air & Space Museum here in Tucson. Most of our exhibits are former military aircraft, but we have a number of historic and modern airliners as well, and I often talk about them with visitors. I grew up reading books about flying, and still read them from time to time. I just finished a remarkably good memoir titled Skyfaring: A Journey With A Pilot, written by a British Airways Boeing 747 first officer named Mark Vanhoenaker. So I was thinking about airliners and history last week when I saw this old travel poster on an aviation nostalgia site:

I recognized the airplane in the poster right away, though most people today would not. It’s a Curtiss T-32 Condor II, introduced in 1933 and flown primarily by Eastern Air Transport (later to become Eastern Air Lines) and American Airways (today’s American Airlines).

The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company built 45 Condors. Most were for Eastern and American, but a few went to the US military, and eight were made as bombers and sold overseas. After their service with Eastern and American, some Condors were purchased by airlines in Chile, China, the UK, and Switzerland.

You probably couldn’t have picked a more economically-disadvantageous time than the early 1930s to introduce new airliners on domestic routes in the United States, but Europeans had enjoyed scheduled airline service for many years, and in the wake of Charles Lindbergh’s historic solo flight from New York City to Paris in 1927, American pride demanded an air travel network too. And believe it or not, even during the worst years of the Great Depression, Eastern and American found plenty of eager customers for their new Condors (though they probably lost money on them, and if it hadn’t been for their lucrative federal air mail contracts, would have quickly gone broke).

The Condor replaced slower, shorter range aircraft like the Ford Trimotor and Stinson Airliner. It boasted a range in excess of 800 miles and a top speed of around 150 miles per hour (the airlines advertised 190 mph, but the Condor’s actual top speed was 176, and 150 was probably more like it). In spite of its longer range, the longest route segments were typically around 350 miles and followed existing air mail routes, marked by regularly-spaced concrete arrows on the ground and, at night, by co-located 5,000-candlepower light beacons.

You could fly coast to coast in 1930, but your trip would entail a mix of short flights by day, overnight train rides, and occasional hotel stays when airline and train timetables didn’t mesh. Flying from New York City to Los Angeles might take four to five days. With the introduction of the Condor in 1933, you could do it in two days and all by air — the Condor’s 12 sleeper berths meant you could fly around the clock. Of course only the wealthy, untouched by the Depression, could afford air travel of any kind.

Here’s a fabulous American Airways promotional film from 1933, featuring the Curtiss Condor and a cabin full of happy passengers bound from Chicago to New York City (I hope you’re not offended by casual racism, apparently a feature of everyday 1930s discourse):

Here’s the thing, though. Aeronautical engineering and aircraft construction were advancing rapidly in the first half of the 1930s, and the Condor was a throwback even before its first flight in January, 1933. It was mostly made of wood and fabric (with bits of metal structure and skin), a biplane to boot with struts and wires to slow it down. Its only “modern” feature was retractable landing gear. It was big, though, and there wasn’t anything else its size, at least in 1933. After watching the film and comparing the cabin shown there with the cabin shown on this 1934 American Airlines timetable,* I believe Curtiss must have offered the Condor in two configurations: an all-seating version for day routes, and a sleeper with facing seats that could be converted to upper and lower beds for overnight flights.

In February 1933, just one month after the Condor’s inaugural flight, Boeing began test flying it’s new Model 247, an all-metal monoplane with retractable gear and deicing boots on the wings. It could carry only ten passengers, but its range was nearly equal to the Condor’s, and it was faster (top speed 200 mph, cruise 188 mph). By May of the same year, the Boeing 247 was in service with Boeing Air Transport (later United Air Lines), Western Airlines, and Pennsylvania Central Airlines.

A year later, in May 1934, Douglas introduced the DC-2, an all-metal monoplane with a passenger capacity of 14, a top speed of 210 mph, and a range in excess of 1,000 miles.

Douglas sold 198 DC-2s. Transcontinental & Western Air (later Trans World Airlines) was the DC-2’s first domestic customer, and it wasn’t long before Eastern and American began replacing their Condors with DC-2s. By 1936, with the introduction of the Douglas DST and DC-3 on domestic routes, passengers could fly coast to coast in 18 hours with only two refueling stops along the way, and it was all over for the old-fashioned Curtiss Condor.

Interestingly, it was American’s own president, C.R. Smith, who in 1935 worked with Donald Douglas to design a larger version of the DC-2, which like the Condor would come in two versions: the DST (Douglas Sleeper Transport), which could carry 24 passengers during the day and 12 at night in sleeper berths; and the better-known DC-3, a 21-passenger day airliner. Both versions could cruise at over 200 mph, with a range of more than 1,500 miles.

It’s impossible to overstate the importance of the DC-3. It revolutionized air travel in the United States and around the world, relegating the Curtiss Condor and Boeing 247 to footnote status. For the first time an airline could turn a profit from passenger revenue alone, independent of airmail contracts. Douglas made over 600 DSTs and DC-3s; later, during and after WWII, it built over 10,000 C-47s and C-53s, military versions of the DC-3. The Japanese built almost 500 DC-3s under license, a source of confusion to Allied pilots a few years later. Fortunately for us, the Soviet Union was on our side during WWII, so we didn’t have to make shoot/don’t shoot decisions when we encountered Russian DC-3s — they too built the airplane under license, manufacturing almost 5,000 of them. I don’t know about the Japanese and Russian planes, but plenty of US-built C-47s, and even some original DC-3s, are still flying today.

By contrast, the Condors have vanished. There aren’t even any in museums, but according to a few sources the wreckage of an American Airways Condor lost in a snowstorm in upstate New York is currently in private hands in Utah, awaiting restoration, and there may be parts of one of the bomber versions in Honduras. Four Boeing 247s remain (only one in flyable condition, probably the one in the photo above).

I mentioned how much nicer it was to fly coast to coast in a DC-3 as opposed to a Curtiss Condor, but apart from how much time it took, there really wasn’t a lot of difference. None of these early airliners were pressurized, so they had to stay below 10,000 feet lest passengers and crew succumb to hypoxia. Your ears would be constantly popping on the way up, and approaching destination airports the stewardess would pass out chewing gum so you could work your jaws and clear your ears during descent. At those low altitudes, of course, rising thermals and sudden downdrafts are rife, so you’d have a bumpy ride to say the least. We’ve all examined those curious airsickness bags in the seat pockets ahead of us, but few of us have ever had to use one. It wasn’t like that in the old days. Every flight was a series of physiological incidents, and stewardesses stayed busy collecting full bags and handing out empties. On the Condor, I’m told they didn’t bother with single-use bags; passengers passed a galvanized bucket around instead.** American Airlines didn’t show that part in the promotional film!

I’m used to airplanes having names in addition to alpha-numeric designations. That’s because I flew for the military, where almost every plane has an official name and several unofficial nicknames as well. In civilian usage, names are somewhat less common. The Curtiss T-32 was called the Condor, but neither the Boeing nor the Douglas aircraft had names. The military version of the DC-3, of course, had lots of names: Skytrain, Dakota, Gooney Bird. Personally, I think the coolest thing about the Curtiss Condor was its name and the high-flying image it brings to mind. Even if it wasn’t in fact a very high-flying airplane, and even if a more accurate image would have been a galvanized bucket!

* American Airways was renamed American Airlines in 1934.

** You know I’m just kidding about the bucket, don’t you?

Update (6/12/22): An aviation historian on Twitter shared an Imperial Airways passenger handout from 1932. I think you’ll find it interesting, particularly the section on air sickness.

Turns out I was only a little off on those galvanized buckets. They were called cuspidors, and in this cabin photo of a British De Havilland 66 Hercules airliner, you can see each passenger was supplied with his or her own!