The body turns in the stream. Where the new bridge crosses the Ganga in five concrete strides, garlands of sticks and plastic snag around the footings; rafts of river flotsam. For a moment the body might join them, a dark hunch in the black stream. The smooth flow of water hauls it, spins it around, shies it feet first through the arch of steel and traffic. Overhead trucks roar across the high spans. Day and night, convoys bright with chrome work, gaudy with gods, storm the bridge into the city, blaring filmi music from their roof speakers. The shallow water shivers.

— River of Gods, Ian McDonald

River of Gods (India 2047 #1)

River of Gods (India 2047 #1)

by Ian McDonald

![]()

Back-alley datarajas, third-generation artificial intelligences, a computer-generated soap opera that becomes self-aware, an anomalous object in the asteroid belt, parallel universes, crooks, cops, CEOs, politicians, expats, neutered humans remade as manga, water wars between semi-independent Indian states, armed drones and slow missiles, a half-human/half-AI woman … an initially-bewildering number of plot threads and unconnected characters, all of which converge in a grand climax. What’s not to like about this sweeping near-future science fiction novel?

I, for one, can’t think of a single thing not to like. I was enthralled, cover to cover.

The first McDonald science fiction novel I read, The Dervish House, rocked me the same way River of Gods did. It too is near-future SF set in another country and culture (Turkey), containing a diverse cast of characters and converging plot lines. It too was enthralling. Are you a William Gibson fan? You will love Ian McDonald.

Be warned, though, that in addition to near-future, cyberpunk-escue science fiction, McDonald also writes fantasy. Perhaps you like fantasy and magic; I do not. I started McDonald’s SF/fantasy novel Desolation Road and gave up on it partway through; not my cup of tea at all. I still have a hard time believing the Ian McDonald who wrote The Dervish House and River of Gods is the same Ian McDonald who wrote Desolation Road.

River of Gods is staggeringly good. Anything else I might say would be full of spoilers. This is one of the very few science fiction novels I’ve read that made me want to go right back to page one and start over.

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned

Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned

by Wells Tower

![]()

I think these are pretty great short stories. I was a bit put off by the first two stories in the collection, but only because they’re about losers. But then, it occurred to me, so are the novels of Charles Portis, a writer I love. And it’s no accident I thought of Charles Portis … Wells Tower has an eye, and a narrative style, that is similar.

The stories are full of sardonic humor, irony, telling details seen from fresh angles. I especially liked the last story in the collection, Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned, a first-person narrative of a Viking raid told from a contemporary-feeling point of view.

Stretched to novel length, I’m not sure these stories would come up to Charles Portis’ level, but it’s a damn good start, and I will look for more.

The Three-Body Problem (Three Body #1)

The Three-Body Problem (Three Body #1)

by Liu Cixin

![]()

I’m a sucker for classic science fiction. This one was recommended by a friend, and I’m so glad I followed up on it.

The Three-Body Problem is a first-contact SF novel. It’s the first installment of a trilogy; without going into detail, the first book relates the initial stages of contact with an alien civilization elsewhere in the galaxy. Presumably the next two books will cover the centuries that must elapse before emissaries of that civilization actually reach Earth, traveling at sub-light speeds. Perhaps I’ve already said too much, but I want to indicate the sweeping nature of Liu Cixin’s vision.

Liu Cixin is a citizen of the Peoples’ Republic of China and his novel is largely populated with Chinese characters. Some of them are products and victims of the Cultural Revolution, and the cultural points of reference are decidedly Chinese. I learned many things about the Red Guard days and modern China while reading this novel; although some readers may be put off by its decidedly non-Western cultural outlook, I found myself fascinated by it. In fact, I wondered if a novel like this would be written in the USA or UK today … in many ways it’s old-fashioned, even Asimovian (though not as sweeping as Asimov’s Foundation trilogy).

The characters, male and female, are well-drawn and believable. The science is often mind-bending, and while many SF authors have administered the kiss of death to their novels by trying to explain quantum physics, IMO Liu Cixin pulled it off. I was never tempted to skip ahead; I devoured every word and believe I grasped the concepts being explained. Those concepts are central to much of the plot, so it’s a good thing the author’s explanations were so lucid.

The second novel, The Dark Forest, will not be available in English translation until August 2015, and so far there’s no scheduled date for an English translation of an as-yet-unnamed third novel. To show you how much I liked the first novel (I rarely rate anything four stars), I’ve pre-ordered the second, and will be looking for a publication date for the third.

Without You, There Is No Us: My Time with the Sons of North Korea’s Elite

Without You, There Is No Us: My Time with the Sons of North Korea’s Elite

by Suki Kim

![]()

Every time I read another behind-the-scenes look at life in North Korea, another piece of the jigsaw slots into place. But even though I’ve read at least a dozen highly-regarded nonfictional accounts of North Korea, ranging from accounts of the lives of ordinary people to prison camp escapees, from low- and high-level defectors to Kim Jong-Il’s abducted Japanese cook, I’ve put together only one corner of the puzzle. The rest remains a jumble, and I have no idea what kind of picture the completed puzzle will reveal.

I’m in awe of Suki Kim, who put herself at risk to teach English to upper-class and inner-circle college boys at a private college on the outskirts of Pyongyang. She wasn’t just teaching, you see, she was keeping diaries and notes for this memoir. Had she been found out, either by the NK minders or the zealous Christian missionary teachers she worked with, she’d have been lucky to be merely deported. She could well have been imprisoned and tried as a spy.

What piece of the puzzle was I able to make out from Ms Kim’s memoir? The fact that visits to relatives (other than immediate parents and siblings) without special permission from the authorities, which is tightly controlled and only grudgingly granted. In school settings such as the one she describes here, even friendships between students and roommates are tightly controlled. She recounts the story of a man who escaped to South Korea during the war, then came back to North Korea as an elderly man, specifically to reconnect with lost family members who’d stayed behind. The man was not allowed to travel to his home village and never did get to see his family again. She recounts the tales of several of her students, none of whom seemed to have real friends, only assigned ones whose duty was to keep an eye on them … indeed as they kept an eye on their own assigned friends … and who were mandatorily paired with new roommates every few months. The students, nevertheless, constantly bragged of parties and gatherings with friends in Pyongyang, lies that are painfully obvious to Ms Kim and the reader. Everyone in North Korea, high and low alike, is a loner, constantly looking over his or her shoulder.

This is some chilling shit, and it fits right in with other details of life in North Korea I’ve gleaned from my readings. Not once have I read a book that even hints at the possibility of a more open life in the north, so I’m beginning to believe that things there are indeed as bad as everyone says.

Oh, and I learned about the “counterparts,” which will keep me up at nights for at least the next year. Orwell ain’t in it. Or, rather, Orwell had it dead to rights.

Thank you, Suki Kim, for risking so much to give us a look at another aspect of life in North Korea.

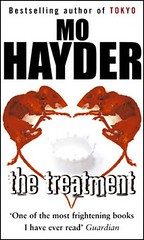

The Treatment (Jack Caffery #2)

The Treatment (Jack Caffery #2)

by Mo Hayder

![]()

Until now, I regarded the novels of Mo Hayder as guilty treats, like jelly beans, something you gobble up while knowing they’re no good for you. Unfortunately, as with the jelly beans in the Harry Potter stories, some Mo Hayder treats taste of vomit.

Big spoiler alert: Mo Hayder introduces a character in the first chapter, a hermit-like collector of found objects, who comes upon a damaged camera in a public park. This character, and the camera he picks up off the grass, becomes one of the threads in Hayder’s story. Over the course of the novel, we periodically drop in on him as he slowly figures out how to safely get the exposed film out of the camera, then teaches himself to develop the film. Hayder makes it appear that he has unknowingly found a piece of crucial evidence, one that would have allowed the police to instantly solve the gruesome murder at the heart of the story, but that he won’t realize what he has until he develops the film … which he eventually does, and then rushes out of the house with it, presumably on his way to the nearest police station.

But Hayder is leading the reader down a false trail. He’s not taking the film to the police. He is in fact the criminal everyone is seeking. It was his camera in the first place. He took the photographs that are on the undeveloped film, and of course knows all along exactly what he has. Hayder springs this on the reader in the final pages.

This isn’t just misdirection or sleight of hand. It’s cheating. It’s as crude and manipulative as ending a novel by saying it was all a dream. I feel used. And angry.

The Treatment is frustrating in many other ways. The bad guys and girls … as in all the other Mo Hayder mysteries I’ve read … are not just inhuman but satanically evil. The details of what they do to their victims are horrifically gruesome, more so in this novel than some of the others because the villains are pedophiles. She has a thing for tight spaces and bondage, and there’s plenty of both here. She lets her victims suffer for far too long while the cops … who are nearly as unsympathetic as the criminals … bumble around, fuck up, lose the thread, take time off for fights with girlfriends and lovers, and go off on unrelated wild goose chases. If there’s a dog in a Mo Hayder story, she will kill it.

The ultimate frustration, however, is at the very end, when Hayder leaves one crucial thread hanging. I’ve gone over my quota of spoilers already so I won’t say what it is, but I predict you will be frustrated too. And maybe as angry at Mo Hayder as I am now.

This is the second of a series of detective stories featuring a cop named Jack Caffery. I’ve read three others, out of order. Is it important to read them in order? I obviously think not; this one … as did the others … contains references to earlier Jack Caffery cases, but I didn’t find that distracting. The stories pretty much stand on their own.

But I don’t like Jack Caffery and I think I’m through with him. He should have been fired three cases ago. As for Mo Hayder, we’ll see. Maybe the next jelly bean will taste better.

The Doubt Factory

The Doubt Factory

by Paolo Bacigalupi

![]()

My rating is based on how I believe I’d feel about this YA novel if I were a young teen, a member of its intended audience. The Doubt Factory left me, an adult reader who enjoys good YA, flat; I only finished it out of respect for Bacigalupi’s abilities as a writer.

If, like me, you’re a fan of Ship Breaker and The Drowned Cities, you might wonder if the same Paolo Bacigalupi wrote The Doubt Factory. It’s plodding, repetitive, and heavy-handed in delivering its anti-corporate message. The characters are thin and barely believable. The action, though there are some tense moments, doesn’t come close to the gritty, harrowing adventures of the young protagonists in the post-collapse worlds of Bacigalupi’s darker YA science fiction.

But I’ve seen this side of Bacigalupi in two other YA books: The Alchemist and Zombie Baseball Beatdown. The Alchemist is an extremely short novel about magic and Zombie Baseball Beatdown is just silly, a garish attempt to trick pre-teen boys into reading. Both have ecological (and in Zombie, anti-corporate) messages, which are common to Bacigalupi’s darker YA novels, but there the resemblance stops. That is how it is with The Doubt Factory: how did we go from Ship Breaker to this?

Who knows? There’s probably a market for wholesome message YA, and maybe there are kids who would like to read about Alix and Moses and their efforts to bring down the entrenched PR/legal/misleading science/paid-for expert structure that exists to deny the harmful effects of tobacco and prescription drugs, but this is very pale stuff compared to most YA novels I’ve read. I was surprised and pleased when Alix actually did something adult with Moses; I didn’t think anything like that was going to happen, based on how the novel had unfolded to that point.

I like YA in general, and I love Bacigalupi’s darker YA. This one? There’s nothing here for an adult reader, and probably not much for teen readers who’ve been exposed to more “adult” YA.