You Can’t Read That! is a periodic post featuring banned book reviews and news roundups.

YCRT! News

In my last YCRT! post I mentioned Rudolfo Anaya’s novel Bless Me, Ultima, a frequently challenged and banned book now being made into a movie. Here are a few other banned books that have received the Hollywood treatment.

Did you know L. Frank Baum’s classic book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz has been challenged and banned again and again? The movie too, and right up to the present day! Well, no wonder … witches, magic, and the notable absence of Jesus: “In one of the most noted cases of censorship efforts against the book, seven Fundamentalist Christian families in Tennessee opposed the novel’s inclusion in the public school syllabus and filed a lawsuit in 1986 based on the novel’s depiction of benevolent witches and promoting the belief that essential human attributes were ‘individually developed rather than God given.’”

The Brits do it too: 20 books that have been banned at one time or another in the UK.

And the Canadians: my sincere apologies for not mentioning Canada’s Freedom to Read Week, Feb 24-Mar 2.

Goodreads. Don’t know if you’ve tried it or even heard of it, but it’s a terrific resource for readers. Here’s a great comment thread on book challenges and bannings.

A public library in Salem, Missouri, was blocking patrons from viewing Wiccan and native American websites on library computers. The ACLU came to the rescue. Reading the linked article, however, I sense library officials don’t plan to change their policies in any significant way.

The other night we watched a Spanish/Cuban movie called Juan of the Dead, a zombie knock-off filmed in Havana. It was rowdy, bawdy, and raucous, with plenty of unflattering behind-the-doors peeks into Cuban life. It’s amazing what gets past the censors sometimes!

The N-word in literature and movies: a thoughtful post with some interesting links. Which prompts me to repost my earlier review of The Book of Negroes:

YCRT! Book Review

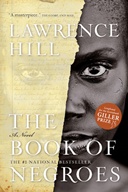

The Book of Negroes

The Book of Negroes

by Lawrence Hill

(published in the USA as Someone Knows My Name)

I learned of this novel while doing research on a favorite area of study, the banning of books. A group of political activists in Amsterdam recently burned The Book of Negroes in effigy, objecting to the title. The news article explained that The Book of Negroes, a novel about the slave trade in the Americas and Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries, took its name from the original “Book of Negroes,” a historical document listing the names of blacks who served the British during the American Revolutionary War and who were resettled along with other loyalists in Canada after the British defeat. Well, I ask you, with an introduction like that, how could I not read The Book of Negroes?

I’m a white American who went to public school during the 1950s and 1960s, which is another way of saying I know almost nothing about slavery in America. Our textbooks gave it short shrift, and I remember a sixth grade teacher in Virginia telling us that slavery had nothing to do with the war between the states. White baby boomers learned what little we know from watching Roots in the 1970s. I didn’t get around to reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin until last year. I didn’t know American blacks fought on the side of the British during the Revolutionary War until I read M.T. Anderson’s historical novels The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Volume 1: The Pox Party and Volume 2: The Kingdom on the Waves.

The Book of Negroes/Someone Knows My Name is the fictional autobiography of Aminata Diallo, who, at the age of nine, is abducted from her African village by slavers, marched to the coast, and shipped to South Carolina where she is sold to an indigo planter. Partially literate when she is abducted, she fully learns to read and write through the kindness of a older, educated house slave. She’s sold to an indigo inspector who teaches her the ins and outs of business and bookkeeping and eventually takes her to New York City where she escapes, just as Americans begin to revolt. She, like many other free and escaped American blacks, serves the British during the war, then is resettled with other black and white loyalists in Nova Scotia.

British abolitionists enlist her to help with a plan to resettle black loyalists in Sierra Leone; she returns with them to Africa. As an old woman, she travels from Sierra Leone to London with her abolitionist sponsor to testify before Parliament, playing a central role in the British decision to outlaw the slave trade. Along the way she is beset with injustices and outrages: her original owner rapes her, her first baby is sold, she’s separated from her husband, her second child is abducted by a white family, she’s forced to hide from runaway slave catchers employed by her first and second owners, she is betrayed by the British and her fellow Africans again and again.

Despite the piety and florid language, I was enthralled by Uncle Tom’s Cabin. I devoured the Octavian Nothing novels and pray for additional volumes. I started The Book of Negroes/Someone Knows My Name with the same level of enthusiasm, but after a few chapters it faded. Aminata is too successful in overcoming the betrayals, debasement, and cruelty of slavery. Certainly, some slaves educated themselves and reclaimed ownership of their lives, but Aminata is practically a 19th century Oprah, frankly not believable. Her story, despite the horrendous injustices of slavery present on almost every page, is relentlessly upbeat. This is not to say that Lawrence Hill’s novel is ever less than a good read; it is just a bit too positively educational for my tastes.

Kudos to Lawrence Hill for tackling dialect, which he does well. Few modern writers would have the balls to try it. Aminata, being the paragon she is, is fluent in three versions of English: Gullah, the “yes massa” language slaves use when speaking to whites, and the King’s English. She also inexplicably remains fluent in the two African languages she knew when she was abducted at the age of nine. There are, unfortunately, a few lapses, with modern phrases creeping jarringly in, as when Aminata tells another black woman, “Nice try.”

Overall this is a very well-written book, one that tells a story too few of us know, a story shamefully absent from our history books. I particularly appreciate the list of recommended reading Lawrence Hill includes in his afterword, because slavery-related material — particularly the stories told by the slaves themselves — is still hard to come by in the United States, and I mean to learn more.

Back to the thing that caught my attention in the first place: book burning and banning. Yes, this book has been burned. It has also been retitled to make it less controversial for American readers, something I consider a form of censorship. Why anyone would object to the original title of this book is beyond me, unless the very word “negro” has become so radioactive it cannot be used in polite conversation. Sadly, that appears to be the case.

When Uncle Tom’s Cabin was banned in many American states, the stated reason was that it would fan the flames of abolition, but the unstated reason was its unflattering depiction of whites. That is certainly true of this novel … after reading it I am distinctly uncomfortable with my white heritage. Of the many stains on white mens’ souls, slavery is one that can never be scrubbed away.