There were stories in sweat.

The sweat of a woman bent double in an onion field, working fourteen hours under the hot sun, was different from the sweat of a man as he approached a checkpoint in Mexico, praying to La Santa Muerte that the federales weren’t on the payroll of the enemies he was fleeing. The sweat of a ten-year-old boy staring into the barrel of a SIG Sauer was different from the sweat of a woman struggling across the desert and praying to the Virgin that a water cache was going to turn out to be exactly where her coyote’s map told her it would be.

Sweat was a body’s history, compressed into jewels, beaded on the brow, staining shirts with salt. It told you everything about how a person had ended up in the right place at the wrong time, and whether they would survive another day.

—Paolo Bacigalupi, The Water Knife

The Water Knife

The Water Knife

Paolo Bacigalupi

![]()

I get lost in Bacigalupi’s near-future science fiction tales of worlds gone awry, ruined by our own greed. Ship Breaker, The Drowned Cities, The Windup Girl: novels of grim but plausible future worlds, populated by desperate survivors, each centered around a few memorable characters looking for a way out, a better life. The Water Knife is such a novel, but the near future presented here is not that far off; it is the American Southwest, finally out of water.

I imagine Bacigalupi’s inner editor urging him to move the setting and timeline of The Water Knife ever closer to the present day and to tighten up the narrative, narrowing the human story down to just a few characters, then tightening up the story some more. What I’m saying is that this is a hell of a read. Gripping, immediate, real. I don’t mean it’s his best to date; I mean it’s his most commercial, written to appeal to a wider audience than his earlier novels (and I don’t mean anything bad by that).

Quibble: I don’t know why Bacigalupi sets The Water Knife in real cities like Las Vegas and Phoenix while fictionalizing other locations (he creates an amalgam of Bullhead City and Lake Havasu City, Arizona, and calls it Carver City). Some obscure legal reason? I found that detail jarring; it made me think of authors like Michener (who invented a fictional state to represent Florida in his novel Space) and Ed McBain (whose Isola represents Manhattan). Why?

Otherwise, total love for The Water Knife, and great respect to the author for reminding us to re-read Cadillac Desert, an important and very readable nonfiction book about water and the American Southwest, clearly the inspiration behind much of Bacigalupi’s work.

Many classify Bacigalupi as a young adult author. Two of his dystopian novels, Ship Breaker and The Drowned Cities, wear the YA label: in those novels the main characters are teenagers. The Water Knife and The Windup Girl are classified as adult science fiction. The characters in these novels are adults, although in this novel Maria, a Texan refugee scrabbling for a living on the streets of Phoenix, turns out (as the story advances) to be a young teenager, and a virgin to boot, someone who would have been right at home in Bacigalupi’s YA novels. But in all four novels the main characters, teens and grownups alike, experience horrific hardships, as dark as anything in adult fiction.

What’s the difference between Bacigalupi’s YA and adult fiction, then? Sex, I think. The kids think about it but aren’t quite ready to engage; the adults are, well, adults. That seems to be the sliding scale. To me, all of Bacigalupi’s dystopian science fiction is solidly adult, never mind the labels. It’s also the kind of adult fiction I’d encourage any teenager to read. Why? Because Bacigalupi has important things to say about what we’re doing to our world and the price we’re going to pay for our greed. And because he’s a damn fine writer.

As a side note, Bacigalupi has written two short novels explicitly aimed at child readers: The Doubt Factory and Zombie Baseball Beatdown. These are not to be confused with his adult (but sometimes labeled YA) fiction. Both are ham-handed and relentlessly didactic morality tales. When I read them I had a hard time believing they’d been written by the same Paolo Bacigalupi I admire.

The Diamond Age: or, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer

The Diamond Age: or, A Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer

Neal Stephenson

![]()

I unreservedly loved the first half of this big science fiction novel. The alternate future, populated by phyles and tribes, is fascinating; the societies of Stephenson’s world in The Diamond Age are logical and internally consistent. Once you get going, everything clicks into place. The characters, Nell and Hackworth and Doctor X and Judge Fang and Miranda and Carl Hollywood, seem quite real, and you can’t help getting wrapped up in their fates.

The second half of the novel, after Hackworth emerges from a decade with the Drummers beneath the waters of Puget Sound. well … there were parts of it I didn’t get. Big sections of the second half felt forced, with characters making long speeches to explain things that could have been shown instead, and toward the end Stephenson makes a mad dash to the finish line. If I had not been as engaged with the story of Nell and her primer and her real and imaginary adventures, I might have had a harder time with the second half.

The strength of the first half is what carried me through the second half, and I’m still so impressed with the first half I think the entire novel deserves a four-star rating. Other readers may not be as forgiving.

Mislaid

Mislaid

Nell Zink

![]()

I bought the Kindle version after reading an enthusiastic review of Nell Zink in the New Yorker, a review that made much of her friendship with Jonathan Franzen, a writer I quite like. That part of the review must have lodged somewhere in my brain, because I kept thinking how Franzen-like are Zink’s descriptions of characters. Which, in turn, I quite liked.

But Mislaid is a rather thin novel. Not necessarily in page count, but in nourishment and staying power. The well-described characters are more allegorical than real, the things they do unrealistic, their successes not of this world.

How interesting, though, that I start reading a novel about a white woman passing for black just days before news broke about Rachel Dolezal … a real white woman passing for black.

Mislaid is an entertaining novel with literary heft and a happy ending, but it’s pretty fluffy. If you want more meat on your novels, go with Franzen.

Seveneves

Seveneves

Neal Stephenson

![]()

Here’s my review of an earlier hard-SF novel by Neal Stephenson, Anathem:

“It’s been years since I’ve read a science fiction epic of this scope, one that creates an entire cosmology from the ground up. Stephenson has vision—a complex vision, though, one that requires much explanation, and I’ll fault Stephenson as a writer for overindulging himself in its explication, most often with long, tedious passages of dialog between the philosophical clock-winders of the concent (yes, there’s also an extensive new vocabulary to learn). Even though Stephenson’s vision is complex, it is comprehensible to anyone well-read in science fiction, and he could have written a tighter book by cutting back on his characters’ academic discussions. Still. It was fascinating to see his world unfold, and there was plenty of space opera action to keep me entertained. Honestly, I didn’t know anyone was still writing science fiction like this—not since Asimov died. If you’re serious about sci-fi, this one needs to be in your library.”

Seveneves, like Anathem, is a hard-SF novel of grand concepts, ideas, and hardware, with a good bit of space opera and an optimistic view of humanity thrown in, reminiscent once again of Asimov. This time around, though, Stephenson dispenses with explication via dialog and instead steps in as third-person cosmic encyclopedia, offering page after page (after page, after page …) of background and explanation whenever he introduces a new idea or bit of space hardware. The novel is 75% encyclopedic background, 25% action. Stephenson seems to be well aware of his compulsive need to explain everything, because late in the novel he introduces a character nicknamed Cyc (real name Sonar Taxlaw), a living encyclopedia, thereby (I think) poking fun at himself.

You know what, though? I didn’t resent the explication, any more than I resented it when Asimov did it. The ideas Stephenson presents, both here and in Anathem, are fascinating in their own rights, and I was never tempted to skip ahead. I did resent a bit of repetition on Stephenson’s part, explaining things twice when once would have done, and I think his opinion of humanity is far too rosy, but in the presence of so many grand ideas and concepts these are minor irritations at best.

Stephenson is becoming the Ayn Rand of hard science fiction devotees. I don’t in any way mean to compare his personality or ideas with Rand’s; what I mean is that Stephenson has the potential to become an influence on futurists, if he isn’t already, and undoubtedly has a cadre of fans at least as obnoxious as Rand’s. I guess I’m one of them!

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2011 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2011 Edition

Patrick Nielsen Hayden, editor

![]()

This is one of three free Tor SF anthologies available for Nook or Kindle download. The anthologies are dated 2011, 2012, and 2013.

I’m commenting on the anthology itself, not the short SF stories contained within (although I will say many of shorter stories struck me as filler). I was annoyed to find the page count heavily padded: each story starts with a title page, then a page with a one-paragraph note on the author, then a page with a one-paragraph editor’s comment on the story to follow, then the story itself (some of which are only two to three pages long), then an end page listing other works by that author. It’s like network TV, where the commercial to content ratio is almost 1:1.

A few of the longer stories, the ones by better-known authors, are worth the read.

I will plow through the 2012 and 2013 editions, looking for the good stories, this time skipping over the filler.

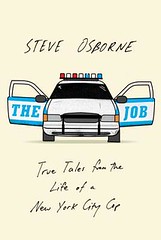

The Job: True Tales from the Life of a New York City Cop

The Job: True Tales from the Life of a New York City Cop

Steve Osborne

![]()

As with Mislaid (reviewed above), an enthusiastic New Yorker review led me to buy a copy of Steve Osborne’s collection of cop stories. Note to self: be more skeptical of New Yorker reviews.

I gather that many of Osborne’s stories were originally oral presentations, and perhaps they worked better that way. In print, they’re repetitive, long-winded, and shallow. A few stories conveyed some of what it is to be a big city cop; most, though, were more about protecting said cop’s ego.

These stories leave a lot out. Osborne doesn’t address even a single one of the many issues we’re all talking about these days: bad cops, corruption, racism, quotas, falsification of evidence, brutality. In his stories, the cops are all good guys and everyone else—especially minorities—is a perp. Anyone who hates cops is a “liberal.”

Apart from admitting that he loved his wife’s little dog and that being a cop put a strain on his marriage, Osborne is remarkably unreflective. There are no lessons here, and not much honesty. I was disappointed.

One I Didn’t Finish

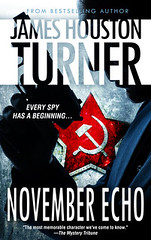

November Echo

November Echo

James Houston Turner

![]()

A reviewer on Goodreads mentioned an iffy start. I’ll say—I couldn’t get past the second chapter. Everything to that point consisted of long, repetitive arguments over logistics and tactics between two Soviet agents being sent to Spain to intercept and return a defector. They argue in Moscow, argue some more in Spain. Page after page of this stuff, all to show us that the young KGB colonel is brilliant and daring, the sexy woman agent a stick-in-the-mud (but one who, you know, will come around).

Can we get to the story, please? All this stage-setting could have been accomplished through plot and action, rather than explication. In the end, I decided waiting for the story wasn’t worth the irritation.