YCRT! is a periodic post featuring banned book reviews and news roundups.

Banned & Challenged Books

I’m not a big fan of lists, but here’s one I can get behind: five subversive children’s books everyone should read.

Parents in Texas go after a high school AP English reading list and school administrators cave, removing Chuck Palaniuk’s Fight Club, Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres, and Ernest Hemingway’s short story Hills Like White Elephants.

Tempest in a Columbus, Ohio teapot: the war over allowing high school freshmen to read The Perks of Being a Wallflower.

The Freedom to Read Foundation successfully fights a Utah school library’s attempt to ban In Our Mothers’ House, a book about the children of a same-sex couple.

Pssst. Do you love bookshelves? Can I interest you in some (drops voice knowingly while opening his raincoat) Bookshelf Porn?

Censorship

Department of Defense blocks liberal and gay-friendly websites, allows access to right-wing hate sites. This is news? It’s been going on since the military first connected to the internet. I started blogging about it nine years ago:

- Military Bans Blogs (Part I)

- Military Bans Blogs (Part II)

- Military Bans Blogs (Part III)

- Military Bans Blogs (Part IV)

- Military Bans Blogs (Part V)

Another wrinkle in online censorship: Court strikes down censorship of negative reviews on website Yelp!

Good review: Censorship on campus in 2012.

YCRT! Banned Book Review

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Uncle Tom’s Cabin

Harriette Beecher Stowe

![]()

When Abraham Lincoln met Harriet Beecher Stowe, he reportedly said “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war.” It’s impossible to overstate the impact Uncle Tom’s Cabin had on mid-19th Century America, indeed the world. Lincoln was dead on.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a barn-burner, even today. What a story it tells! By following the lives of a small cast of black and white characters over a five-year period, it rubs salt in every societal wound: those that were open to public debate, those no one dared speak of, those that live on today.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is about slavery, forced miscegenation, eugenics, the destruction of families. It’s about the underground railroad. It’s about the still-shocking collusion between the federal government and slave states in passing laws not only making it illegal for citizens of free states to help fugitive slaves, but mandating their cooperation in returning slaves to their masters. It’s about the pervasive white fear of slave uprisings. It even brings up the idea of reparations, a subject that to this very day causes white brains to explode.

When Uncle Tom’s Cabin was published, in 1852, it was immediately banned in the South as abolitionist propaganda. Throughout the 20th century and up to the present day, conservatives and liberals continue to challenge the book’s inclusion on school reading lists, citing objectionable language: niggers (house & field varieties), darkies, “the despised race,” mulattoes, quadroons, octoroons, pickaninnies, mammies, Sambos … language that frankly makes me squirm … but what leaps out even more forcefully is Stowe’s condemnation of Christianity as practiced by white preachers and congregations. There’s no doubt in my mind this is the unvoiced reason behind most contemporary objections and challenges.

Reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin, I’m uncomfortably reminded that I grew up with people who used the same words and held the same benighted beliefs. I attended churches where racism and an implicit approval of slavery was still espoused from the pulpit. Sadly, there’s plenty of evidence the kids I grew up with passed the poison on to their children and grandchildren.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin hasn’t lost its mojo: it still has the power to stir. But great parts of it are offensively unbelievable to modern readers, probably the result of Harriet Beecher Stowe pulling her punches, not wanting to completely alienate her intended white audience, too timid to say all the things that were in her heart. An example: in 1852, it was conceivable to white readers that a little white girl could swoon and die from nothing more than an excess of sensitivity, waving her lace kerchief to sobbing, devoted slaves as she drifts away. A little black girl, on the other hand, could be torn from her mother, forcibly impregnated by a white master, see her own child in turn sold downriver for another white man to fuck, be worked almost to death in the cotton fields once she lost her looks, whipped and kicked like a recalcitrant mule … and express no emotion more forceful than annoyance, coarse creature that she is.

And Uncle Tom … I thought I knew what it meant to call someone an “Uncle Tom.” I didn’t know the half of it. Tom loves his white masters. He’ll do anything for them. When he’s taken from his wife and children and sold downriver, he goes willingly, hoping for the best. He embraces the white man’s Jesus, the cruelest character in the book: absent, uncaring, the emptiest of empty promises. Even as Tom exhales his final breath, the life literally beaten out of him, he cannot imagine raising a hand against a white man. Brother, you call someone an Uncle Tom, you’re really calling him something!

Condemned and praised, Uncle Tom’s Cabin is everything it’s accused of: horrifying, upsetting, offensive, thought-provoking, moving. It started a war. It ended slavery in this country … at least for now.

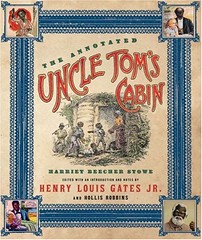

Note: I read an illustrated and annotated version. The 150 black and white illustrations and 32 pages of color artwork are of historical interest and may be worth the extra expense. The notes and commentary by Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Hollis Robbins, on the other hand, are trivial and distracting … they read as if written by fussy 12-year-olds. If you’re considering buying a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, skip this annotated version and just buy the real thing.