“In Paris, the evenings of September are sometimes warm, excessively gentle, and, in the magic particular to that city, irresistibly seductive. The autumn of the year 1938 began in just such weather and on the terraces of the best cafes, in the famous restaurants, at the dinner parties one wished to attend, the conversation was, of necessity, lively and smart: fashion, cinema, love affairs, politics, and, yes, the possibility of war — that too had its moment. Almost anything, really, except money. Or, rather, German money. A curious silence, for hundreds of millions of francs — tens of millions of dollars — had been paid to some of the most distinguished citizens of France since Hitler’s ascent to power in 1933. But maybe not so curious, because those who had taken the money were aware of a certain shadow in these transactions and, in that shadow, the people who require darkness for the kind of work they do.” — Mission to Paris, Alan Furst

Mission to Paris

Mission to Paris

by Alan Furst

![]()

Furst’s latest, Mission to Paris, seems different from earlier novels in his Night Soldiers series. It is not as atmospheric, not as noir. Furst’s omniscient narrator is more omniscient than normal, explaining more than is strictly necessarily. In the previous novels, Furst’s characters were people no one would ever have heard of in real life, ordinary men and women working in great secrecy behind the lines to defeat or disrupt the march of fascism in the 1930s and 40s. If they failed, they died in obscurity. If they succeeded and struck a major blow against Hitler, they still died in obscurity. In this novel, the main character is a (fictionally) well-known movie star. He can’t fade into obscurity: succeed or fail, his death will be noted. I’m not sure exactly why this should make a difference, but to me it does … perhaps the presence of the movie star makes it harder for me to suspend my disbelief and let the novel take me where it will.

These minor objections aside, Furst still has the ability to make the frightening history of this era come alive. In this case it is the history of France in 1938 to early 1939, on the eve of the German invasion, a France where powerful people … bribed with German money … are working hard to make things easy for the Reich. Some of the scenes grab you by the lapels and dare you to compare what went on then with the actions of our own rich overlords, politicians, and complaisant media today. Powerful stuff.

Mission to Paris is an exciting and thoughtful story with some very tense situations and not a few hairsbreadth escapes … and a nice love story thrown in.

I Am Not Sidney Poitier

I Am Not Sidney Poitier

by Percival Everett

![]()

I belong to a book club; we wanted to read a “happy book” and this was our September selection.

One of the earliest literary traditions is allegory, where the author contrives a representative character to act as a straight man or foil in contrived situations, the outcomes of which are supposed to teach us. Some allegories are comedic (Candide), some are tragic (Oedipus Rex). If I’m going to read about contrived characters in contrived situations … just as a personal preference, mind you … I want the lesson to be worthwhile. That is not the case here.

Flat Stanley … oops, Not Sidney … is as unlikely a character as The Fresh Prince of Bel Air. A black boy who looks like Sidney Poitier, who just coincidentally shares the actor’s last name (but no DNA), whose first name is meant to mock his last name while at the same time pointing out his physical resemblance to his namesake, is born to a single mother who makes a wise investment and, upon her early death, leaves him filthy rich. He winds up living with Ted Turner and Jane Fonda, goes to high school and then college, then drops out and attempts a drive through the Deep South, where he is killed for his money.

Contrived character, contrived situations. What are the lessons? Education is mostly bunk. Light-skinned blacks look down on dark-skinned blacks. People treat you differently when they know you’re rich. Poor whites in the Deep South still hold primitive views on race. People will kill you for your money.

Not exactly Native Son, is it? And for sure nothing we haven’t heard before.

What did I like about I am Not Sidney Poitier? I liked Not Sidney’s dreams. That’s where all the important stuff happens. I liked the way Percival Everett gradually led me to the realization that the peckerwood cracker working with the faux nun at the backwoods church had already killed Not Sidney, and that the last part of the book was being narrated by a ghost.

I’m glad Jane Fonda did not have a speaking role. Ted Turner’s digressive non sequiturs were amusing for the first few pages. But then we meet Not Sidney’s money manager, who talks a lot like Ted. And then we meet Not Sidney’s favorite professor, who also talks like Ted. I would have been horribly disappointed to find Jane talking like Ted too. What am I saying? That all the characters save Not Sidney are as similar and shallow as can be, and so is Not Sidney when he is not dreaming.

The humor in I Am Not Sidney Poitier is sitcom-level funny, and I suspect that if it were possible to add canned laughter to the printed page Percival Everett would have done so. I wouldn’t be surprised to learn the audio book has a laugh track. The novel is definitely allegory, but the lessons are trivial ones. I would not classify this as a “happy book.” Or a successful one either.

Perfection

Perfection

by Walter Satterthwait

![]()

Enthusiastic friends are always plugging mystery novels, but when I read them my excitement rarely matches theirs. Such is the case with Walter Satterthwait’s Perfection, a (to me) box-stock serial killer police procedural with two semi-interesting cops, the standard cast of ancillary characters, and of course the serial killer himself, hiding in plain sight through a contrivance so far-fetched I nearly threw the book across the room when I came to the reveal … and I would have, too, if there had been 50 or 60 pages still to go, but Satterthwait didn’t chuck the grenade until the third to last page. This is the stuff of made-for-TV movies, shallow and sensationalistic.

I know there are better mystery writers. Far better. Henning Mankell, for one. Ed McBain for another. Elmore Leonard. Mo Hayder. I’ll continue to listen to my friends, of course … after all, friends turned me on to Henning Mankell, Ed McBain, Elmore Leonard, and Mo Hayder in the first place. But I’ll expand my mystery horizons by looking up some recent crime & mystery award winners, and if I find any good ones, you’ll read about it here.

Classified Woman

Classified Woman

by Sibel Edmonds

![]()

I had an odd reaction to this book. I believe everything Sibel Edmonds says about the FBI, congress, and the executive branch taking extraordinary pains to cover up internal malfeasance. I believe her when she describes what they do to employees who try to bring them unwelcome messages, and I believe her descriptions of the ways they get back at whistleblowers. I believe much of what she reports about our government’s failure to act on clear and specific intelligence that al Qaeda was about to attack, leading to our failure to prevent the terror attacks on 9/11. She drops tantalizing hints about some of the pre-9/11 intelligence that was ignored, including a frightening detail I’ve not seen reported elsewhere: that al Qaeda was planning to use young women in the “next wave” of terror attacks on the West.

At the risk of being labeled a “9/11 truther,” I believe everything Sibel Edmonds says about our government’s continuing efforts to keep its colossal failures hidden from the public, and its refusal to hold anyone accountable. I believe her accusations of corruption at the highest levels of our government.

My trouble is with Sibel Edmonds herself. In her recounting of confrontations with co-workers and supervisors at the FBI, her story seems too self-serving, her villains too cartoon-like. Her account is full of fishy details that make her seem less a person of principles and, at least when it comes to certain former FBI co-workers, more a person bent on personal revenge. In short, I don’t accept the wholly-innocent, goody two-shoes image Sibel Edmonds tries to project.

Also odd: no other reviewers of Classified Woman share my discomfort. I’ve explored reader reviews on Goodreads, Amazon, and B&N, and have searched for others on Google. Everyone seems to buy her story, lock, stock, and barrel. Very strange. I can’t be the only one to think there’s something wrong with her account.

In the last third of the book, Edmonds describes her post-FBI work as an activist working on behalf of other persecuted whistleblowers, and this part of her narrative was generally uplifting and positive. In her post-FBI life, Sibel seems to be what she presents herself to be, and I can only admire her perseverance.

And that’s where this interesting book left me, ashamed of my government, more than ever aware of and watchful for high-level lying and coverups, yet mistrustful of the messenger herself.

Together We Fly: Voices from the DC-3

Together We Fly: Voices from the DC-3

by Julie Boatman Filucci

![]()

I’m a retired USAF pilot with a lifelong interest in aviation, a volunteer tour guide at one of the largest air museums in the USA. You can’t talk aviation history without talking about the DC-3, and I’ve been looking for a copy of this book since it first came out. I’m very happy I finally was able to locate one and read it.

Julie Filucci does a thorough job tracing the story of the DC-3 from its beginnings to the present day: the early 1930s airline company requirements that led to the DC-1 and DC-2, then to the DC-3, which virtually overnight became the aircraft of choice for airlines all over the world; its history with the airlines and then the military; its transition from the major airlines to smaller regional passenger and cargo carriers; its role as a gunship in the Vietnam war; its popularity in remote regions of the world; and its its many fans today, who flock to airshows to see it. Each chapter contains stories from the men and women who designed it, built it, flew it, maintained it, treasured it.

It’s a fine read, and for me at least a useful one: many of the talking points the museum gave me to follow when telling visitors about our restored C-47 (the military version of the DC-3), it turns out, are slighlty inaccurate, and I will have to revise my presentation.

The Price of the Stars (Mageworlds #1)

The Price of the Stars (Mageworlds #1)

by Debra Doyle

![]()

I read an enthusiastic review of the Mageworlds series on a popular web site, one that gave me the impression Debra Doyle was breaking new ground. Much of the science fiction I’ve read lately has been derivative, so I thought I’d try The Price of the Stars, the first book of the series. I’m disappointed to say there’s nothing new here. What I read is essentially a Star Wars knockoff, a swashbuckling pirate story set in space. Only with less sex and flatter characters.

Apart from the ritual incantation of sic-fi devices like “hyperspace” and “cloaking devices” and “healing pods,” there’s no science here. The characters, including the gratuitous alien, a member of a saurian race of grumpy hunter-killers, are relentlessly stereotyped. Minus the interplanetary backdrop, there’s nothing futuristic here … people, society, and governments haven’t changed a bit from the present day (even the communications devices seem little more advanced than cell phones).

The heroes waltz through interlacing beams of death rays with scarcely an injury (which in any case they can cure by hopping into the nearest healing pod), but of course every bad guy they point their blasters at dies instantly. Oh, and there are Jedis, only here they are called Adepts. The evil empire our heroes do battle with, the Mageworlds, turns out not to be alien at all, just some planets populated with other humans, only these humans have embraced the Dark Side. And they too go down before our merry band of space pirates.

Debra Doyle loves short chapters. The book is divided into uniformly brief chapters of four to five pages each, regardless of whether there’s any structural reason for chapter breaks. You’ll be with one of the characters in the middle of a blaster battle when you come to a page break and new chapter heading, but instead of a change of scene or shift in perspective, Debra plops you right back into the ongoing blaster battle, right back into the head of the same character. Debra, this is not why God gave us chapters.

I’ll give The Price of the Stars this: it’s readable and there’s action on nearly every page. It’s rip-roaring space opera aimed at a young adult audience. But I was looking for something new, something a bit more adult, something to engage my imagination. There wasn’t anything here for me.

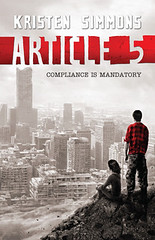

Article 5

Article 5

by Kristin Simmons

![]()

I quit a little over half-way through, so didn’t rate the book. I love young adult dystopian fiction, but this one doesn’t fit in the category. Kristen Simmons can’t seem to choose between channeling Margaret Atwood (which I wish she had) or writing a Harlequin romance (which I wish she hadn’t). The heroine, Ember, is one of the most irritating girls I’ve ever met, stupid and stubborn; if I’d been the hero, Chase, I’d have abandoned her in the woods 50 pages in.

Kristen Simmons doesn’t bother much with research: her descriptions of guns and shooting are vague, as if she were paraphrasing things she’d read elsewhere, and when Chase and Ember discover a motorcycle in a garage she goes badly off the rails, with Chase mooning about owning a “crossover Sportster” that to his sorrow didn’t have a “custom transmission” — later, when they make their getaway on it, Chase accelerates by “stepping on the pedal.” Did she think no one who’d ever ridden a motorcycle would ever read her book, or did she simply not care? Enough. Good luck to you, Chase. Ember, grow a brain, okay?