“The ghost was her father’s parting gift, presented by a black-clad secretary in a departure lounge at Narita.” – William Gibson, Mona Lisa Overdrive

|

Mona Lisa Overdrive, by William Gibson When I started reading William Gibson’s novels and short stories, I did not realize that they were component parts of larger stories. When I read Count Zero, for example, I did not realize it was part of the Sprawl trilogy, along with Neuromancer and Mona Lisa Overdrive, or that All Tomorrow’s Parties was part of the Bridge trilogy, along with Virtual Light and Idoru. So I read them all out of order, and when I’d see references to the Sprawl (the domed concentration of Eastern Seaboard cities) or to the community living on the closed, earthquake-damaged San Francisco Bay Bridge, I regarded them as common elements in disconnected stories. Because, in fact, you can read Gibson’s novels out of order, and even mix novels from different trilogies, and be quite satisfied. Gibson is a terrific storyteller, and each novel stands alone. But now that I’ve figured out the trilogy structure of the Sprawl and Bridge novels, I’m going to have to read them again, this time in order, because I know I’ll see more than I saw first time around. Good. I’ve been looking for an excuse to read more Gibson. |

|

You Shall Know Our Velocity, by Dave Eggers I loved Eggers’ What Is the What?, the novelized memoir of a “lost boy of Sudan.” I hated Eggers’ A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. So I picked up You Shall Know Our Velocity with trepidation — and hated it immediately. I forced myself to finish it — unlike Heartbreaking Work, which I put down after three chapters — out of a sense of fairness to Eggers’ reputation. As with Heartbreaking Work, Eggers writes about characters who are purposely and selfishly unable to cope, young men who seize upon everyday tragedies (the kind the rest of us manage to overcome and move beyond, because we must) as excuses to abandon responsibility, drop out, and indulge in masturbatory idleness. Maybe it wouldn’t be so bad if Eggers’ idle shitbirds didn’t spend entire novels trying to get us to feel sorry for them. Of course I realize Eggars wants us to dislike his characters. He deliberately makes them unsympathetic. And I’d go along with it if Eggars had something important to say, as Dostoevsky said with his character Raskolnikov. But Will and Hand, the two jackoffs of Eggers’ novel, have nothing to teach us. And they poured gasoline over a cow, set it afire, and watched it burn to death. If you can forgive Will and Hand — and Dave Eggars — after reading that (even if Eggars did make it up), you are a better person than me. p.s. Eggers is a good writer, and my 1 1/2 star rating has nothing to do with the quality of his writing. It is based on moral revulsion. Just want to make that clear. |

|

Norwood, by Charles Portis A brilliant short novel about shitkickers in the 1960s. Norwood gets a hardship discharge from the Marines and comes home to Ralph, Texas, taking back his old job at the service station to support his overweight sister. Increasingly restive after his sister marries a sponging good-for-nothing who moves into the house Norwood and she share, Norwood falls in with a grifter, has an adventure delivering stolen cars to New York City, meets a girl on the Trailways bus home, and brings her back with marriage in mind. This was one of the most fun stories I’ve read in some time; I can’t believe I hadn’t heard of it before. |

|

Impact,, by Douglas Preston Here’s a beach book for you, a Michael Creighton-style science-fiction potboiler about a sharp girl who finds the impact crater of a mysterious meteorite, an ex-CIA agent who finds another crater on the exact opposite side of the world, a dedicated young scientist who realizes something on Mars’ moon Deimos is emitting gamma rays, and a host of bad guys trying to stop these three in their tracks. Meanwhile aliens menace the earth and moon by poking holes through them. Good stuff, well written, suspenseful, hard to put down. I inhaled this story in one sitting. |

|

Directive 51, by John Barnes When I pick up a book by an author new to me, I patiently read the first couple of pages before buying or borrowing it. You can tell whether you’ll like a book after reading two pages, right? Not always. It didn’t work with Cory Doctorow’s Makers. It failed again with John Barnes’ Directive 51. Failed how? Failed in that I didn’t pick up on the long expository speeches made by characters later in the novels, the poor writer’s way of moving a complex story along. Both authors had the good sense to start their novels with action, vivid scenes, and interesting characters, wisely saving the Ayn Rand-style speechifying for later chapters. I felt gypped with I got to those parts, and in fact I was gypped. I will not read either author again. And what a shame, because both writers started off with interesting ideas, ideas robust enough to build good stories on. In Doctorow’s case, a story about near-future entrepreneurs finding ways to build new societies — and new kinds of social contracts — amidst an economy destroyed by runaway capitalism. In Barnes’ case, a story about radical environmentalists releasing organisms that destroy rubber, oil, and electronic components, and the way society and government respond to the new order suddenly imposed upon it. Authors like Margaret Atwood, Dennis Mitchell, and William Gibson take such ideas and spin engrossing novels from them. Their characters live and act within the givens of fictional near-future worlds. They don’t stop to explain the givens; we learn about them in the context of the story. In Oryx and Crake, the characters don’t lecture us about greedy corporations exhausting the world’s natural resources and destroying agriculture through the introduction of genetically-engineered seed and hybrid animals. They live in their ruined world and whatever history we learn is the imperfectly-understood history the characters pick up along the way as they struggle to stay alive in a hostile environment. From now on, when I’m standing in the library or Barnes & Noble with an unknown author in my hand, I’m opening the book two-thirds through. That’s where the hacks bury the speeches. Just think . . . if I’d have known this as a pimply-faced teen, I’d have been spared Atlas Shrugged! |

|

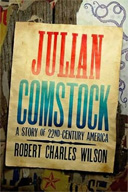

Julian Comstock: A Story of 22nd-Century America, by Robert Charles Wilson A well-told story about a diminished world, set about 150 years in the future after several near-apocalyptic events and a return to a steam & sail-powered world dominated by religion. The narrator is a young man well-placed to tell about both rural and urban society, history, and the battles for power between the secular government and the church. I was entertained throughout, swept along by the narration and action, and thoroughly enjoyed the read. The America of Julian Comstock, I reluctantly admit, is a more believable one than the future depicted in Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Liebowitz (the great classic of the genre), but not as disturbing or provocative as the one depicted in Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood. |