In its last years, West Berliners covered the Wall (which came down 20 years ago today) with paint, political statements, street art, and graffiti. Many Americans, when they picture the Berlin Wall, see it in color.

That’s not what I remember. Both times I saw the Wall, it was forbiddingly gray.

In 1966, Donna and I were living in Wiesbaden, West Germany. Since we worked for the US military we were eligible to travel on the US Army’s troop train from Frankfurt to Berlin. We decided to take a cheap vacation.

The train traveled through West Germany during daylight hours, reaching the East German border at Marianbad at nightfall. Passengers had to stay in their cabins as a Deutsche Demokratische Republik steam locomotive hooked onto the front of the train and armed DDR Volkspolizei guards took up positions at both ends of every car. We were 19 or 20 years old, and absolutely terrified. Commies! With machine guns!

We rolled across East Germany in the black of night. The towns and train stations we passed through through were blacked out as well; we couldn’t see a thing. The train stopped in Potsdam, just outside West Berlin, just before sunrise. We were finally able to get a look at life in the East, as workers started their day in the rail yards. All was steam and iron, a live version of a Soviet Realist mural, with men leaning into enormous wrenches, gigantic gears turning, sparks flying, mighty dynamos, black locomotives. Soon a US Army diesel locomotive hooked on and towed us into the West Berlin station, where we breathed a sigh of relief.

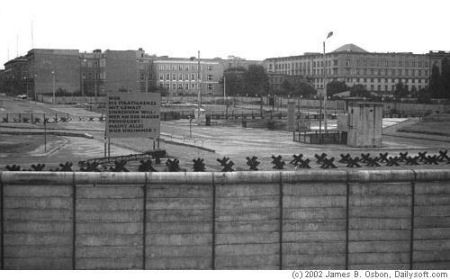

The Wall was gray, but in 1966 pretty much all of Berlin was gray, East and West. Gray clouds, gray cobbled streets, gray buildings, gray people in gray hats grimly going about their business, blackened ruins here and there like rotted teeth . . . and always, that grim gray Wall.

The only color we saw was on the one night we blew our small wad nightclubbing; West Berliners our age lived for evenings on the town, Radio Caroline, impassioned political debate, rock music, hole-in-the-wall clubs. We were broke, so we did whatever was free: Checkpoint Charlie, a visit to a museum where they showed relics of successful Wall crossings (and photographs of dead and dying bodies in the no mans’ land on the East side of the Wall, unsuccessful escapes), a tour of the burned out bunkers below Tempelhof airfield. There was no going into East Berlin, and we wouldn’t have gone in any case . . . we totally believed we’d be arrested and sent to Siberia if we set one foot over the line. Back in Wiesbaden two days later, we felt happy, free, and safe, ever so thankful we hadn’t been born behind the Iron Curtain.

In 1981, Donna and I were back in Europe. I was an Air Force captain, flying F-15s at Soesterberg Air Base in The Netherlands. US Air Forces Europe decided to send all combat-rated aviators and their spouses on know-thine-enemy tours of East Berlin. Donna and I took the troop train again, this time with three other USAF couples from our squadron.

Everything was the same as before except that by 1981 the East Germans had graduated from steam to diesel, and we, older and wiser, weren’t were less afraid of the commies. The fact that we were traveling with friends and had brought along plenty of booze for the trip may have helped in that regard. I remember trying to engage a VoPo guard in conversation after we’d crossed into the DDR, but he was used to drunken American officers and stonily ignored me.

West Berlin in 1981 was a different city, bustling and prosperous. The Wall itself, and what we could see of East Berlin on the other side, was still gray, but West Berlin was clean, bright, and colorful. During the first three days we toured US, British, and French military installations in West Berlin; at night we dined at the American, British, and French officers’ clubs. On the fourth day we crossed into the Soviet sector . . . East Berlin, still as gray as ever. We joked about crashing the Soviet officers’ club, but in fact our movements and time on the other side were strictly limited.

Under our status of forces agreement with the Soviets, we military members had to wear our dress uniforms and surrender our passports as we passed through Checkpoint Charlie. We had a US Army guide, but he gave us plenty of rope and we could walk around on the streets. The East German comrades generally pretended we weren’t there. Years of officially not seeing the prosperity on the other side of the Wall had trained them not to see us. By us, I mean we guys. The comrades had a harder time pretending not to see our wives, who didn’t wear uniforms and had gone out of their way to dress well and expensively, to have their hair done beforehand, and to look stunning, stylish, and Western. Lots of East Berliners sneaked peeks at our girls.

In a park near a Soviet war memorial, we were approached by an old lady. She asked us, in a mixture of German and English, if we knew her uncle in Chicago . . . we of course assumed she was an agent provocateur sent to entrap us, so we pretended she wasn’t there. Our guide later explained to us that the Stasi gave old people more leeway since they were less likely to try to escape than younger people, or perhaps because if they did escape the state would save a few marks in pension payments . . . they could occupy apartments close to the Wall that were off limits to anyone else, and they could approach and talk to visiting Americans without fear of reprisal. I wish now I’d been brave enough to ask for her uncle’s name and address.

We went into a big department store to buy Russian fur hats, but they had only extra small sizes in stock. There really wasn’t anything else to buy there, and even if there had been, we didn’t have the time to stand in multiple lines to buy it: the store was set up workers-paradise style, with one line to order the product, a second line to pay for it, yet a third line to actually get it. Outside, in a plaza, we tried East German curry wurst from a sidewalk vendor; it tasted like sawdust and was almost inedible. East Germans had BO, bad teeth, decidedly unstylish clothing. We walked across the campus of Humboldt University through throngs of earnest revolutionary students from Africa, Cuba, China, and Southeast Asia. They had BO too.

Near the end of our tour we were allowed to visit a hard currency store open only to Soviet officers and diplomats . . . or anyone with US dollars. There we could buy Polish vodka, shiny samovars, caviar, and those Russian nesting dolls. We men loaded up, stuffing bottles of vodka into our greatcoats, while our wives bought out the entire stock of dolls.

During our day in East Berlin, the only people other than our guide to talk to us were the old lady in the park, the curry wurst vendor, and the attendant at the hard currency store. I’m sure we all thought they were KGB; I know I did.

East Berlin, unlike the West Berlin of the early 1980s, was still riddled with WWII ruins. In fact, East Berlin and the DDR were dying, but we didn’t know that. At our base in Holland, we trained daily to fight a powerful, modern enemy, the USSR and its Warsaw Pact allies. And of those allies, the jewel in the Warsaw Pact’s crown was East Germany. We had no idea that eight years hence the Wall would come down. It seemed to us then as if it would be there forever.

Both times we visited the Wall, the Cold War was at a protracted peak. In 1966, we still feared a sudden nuclear attack by the USSR, and the military bases in Wiesbaden still practiced for it . . . I remember the air raid alert sirens going off every Wednesday at noon. In 1981 we worried about an overwhelming conventional armor and infantry attack through the Fulda Gap, and as far as we knew, the USSR and its Warsaw Pact allies had the firepower to pull it off. It was deadly serious.

Deadly serious, and gray. That’s what I remember of the Wall.